The Pop Art Movement, Art Appraisals, and International Art Deals

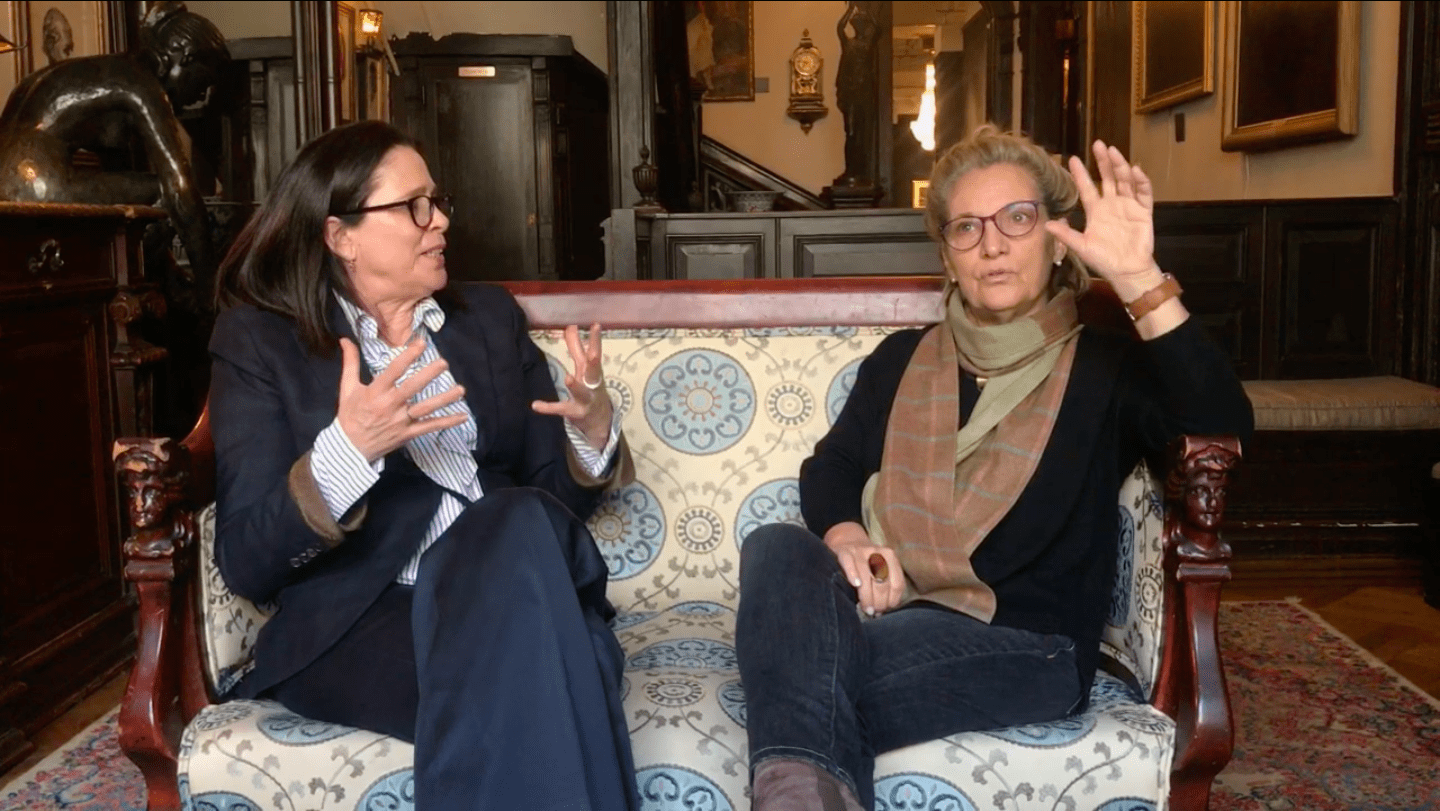

A dialogue with art appraiser Megan Hay Guglielmo and Argentinian art dealer Nelba Valenzuela-Delmedico.

What was it like to party with Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, and Jean-Michel Basquiat? What is an international art dealer’s biggest ‘James Bond’ moment? And has the presence of women in the art world really shifted over the past few decades? Meet Megan Hay Guglielmo, an art appraiser who experienced the rise of New York City’s pop art movement first-hand in the 1980s, and her colleague, Nelba Valenzuela-Delmedico, an Argentinian art dealer with thrilling tales of international art adventures. In our most exciting interview yet, we sit down with these two true power women at The National Arts Club to discuss pivotal moments in art history, art forgeries, feminism, and a little RBG.

PARTYING IN THE 1980s

What is your background and how did you get started in the art world?

NELBA: I moved from Argentina to New York 29 years ago with a mission to put a South American gallery on the map in the art market. That was the beginning. The art market was a difficult place in the 90’s, but I was coming from a country with many problems so it did not seem that bad to me. In fact it felt invigorating, I began to feel a new energy, and I let myself go with the flow of the new direction. I learned the rules of the art market and I adapted to the culture. I was like a sponge absorbing new information and what was happening. The expansion was enormous, everything that I wanted to see and be part of was here.

How about you, Megan?

MEGAN: I go back many generations in New York City, and so my father’s side is relatively artistic. They did a lot of relief work for the churches here in Manhattan, the reason why they came is because of that. They were sent here by the Pope. I’ve been in the arts all my life. Ever since I was a young girl I started painting and drawing. I studied at all the major art schools in NYC. My mother was rather bohemian, and I just never stopped drawing after that. I pursued art because it was so natural for me to do. I moved to Europe, did some studying in Florence, and then I did some studying in North Africa.

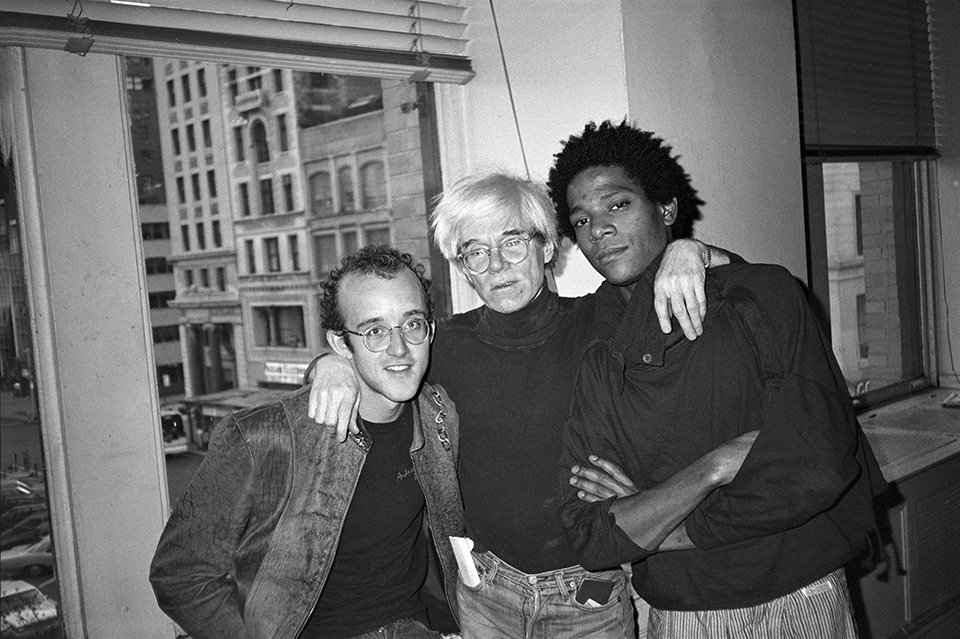

What was it like to party with Warhol, Haring, and Basquiat in the 80s?

MEGAN: We were very young, and nobody had any idea that we were in the middle of something big and interesting. The city was basically abandoned at the time—it was a transitional time for the city of New York—and I think the world. It was in the air. It was so obvious that change was happening. When there’s nothing, then great things happen. There was nothing to lose at that point—it was poverty stricken.

NELBA: What year was it?

MEGAN: The mid-70s and the 80s. The Lower East Side was completely abandoned. Buildings were crumbling to the ground. Most of Manhattan was relatively dangerous. There was crime rampant everywhere. Everybody knew that they were in the presence of something special. Amongst all the artists we knew that Jean-Michel. There was some kind of light coming out of him that was unlike anybody else, and it was time-appropriate as well. I think I actually was at a party with Obama at one point in the Lower East Side.

NELBA: Really, do you? I would love to be there!

MEGAN: Well, you know, New York is a special place, but the 80s were great because there was something definitely happening. What was his name, the filmmaker? The black filmmaker who I just adore who always wears a baseball hat.

NELBA: Spike Lee?

MEGAN: Spike Lee! I think it was Spike Lee’s party where Obama was at. I mean, the Lower East Side had these huge parties and anything could happen.

NELBA: That was the place to be.

MEGAN: Oh my god it was fantastic. Nothing like today.

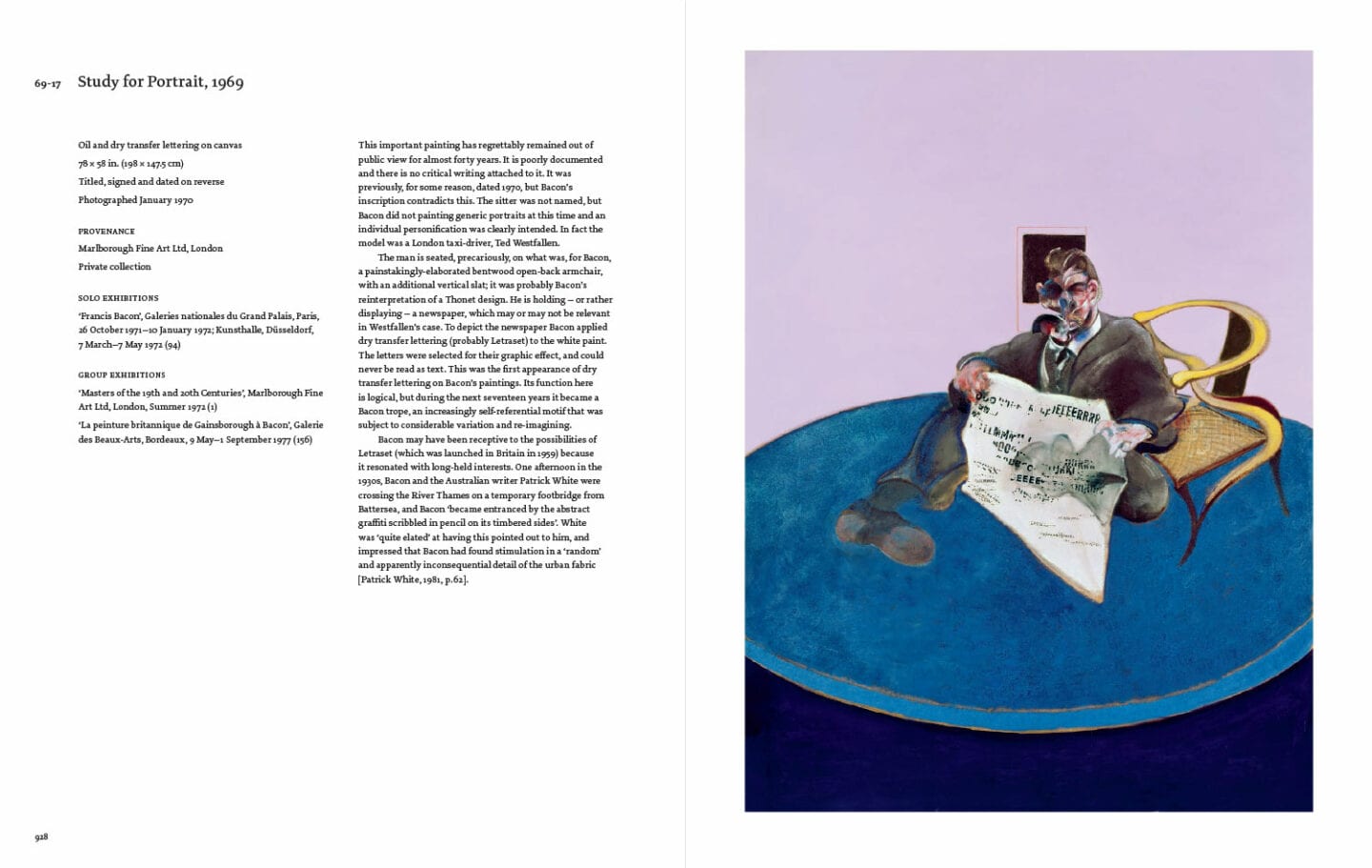

Tell us about The Mudd Club.

MEGAN: Oh! It was such a dump! But it was fantastic, the energy there. Every night there were these bands that were coming from the Bronx. The music was spectacular. Keith Haring and I went to school together. He was very close with Jean-Michel, and Andy Warhol used to hang out there, and that’s how Jean-Michel met Andy Warhol. We all were hanging out around Andy at the time, but Jean-Michel and him became close friends. This was around the time when Warhol wasn’t being acknowledged in the art world, it was kind of passé at that point. Everybody knew this thing was happening.

NELBA: He was establishing another concept of art, so he was changing the perspective.

MEGAN: Right. And I think there was always this question of Warhol validating his art.

NELBA: I think still now…

MEGAN: Still now, but it’s such great stuff. I mean, the guy’s a genius. At the time, I never knew. We were all at art school trying to find our way.

NELBA: When somebody’s ahead, everyone says, ‘Oh he’s nobody.’ But he put a mark.

MEGAN: Oh, he did. And I think he was brilliant, truthfully. He saw things as they were and could translate them.

NELBA: Well after him, many followed the Pop Art movement and his concept.

MEGAN: Yes. He changed our vision. And when you do that as an artist, that’s pretty much what you want to accomplish.

NELBA: This is the mission of the artists.

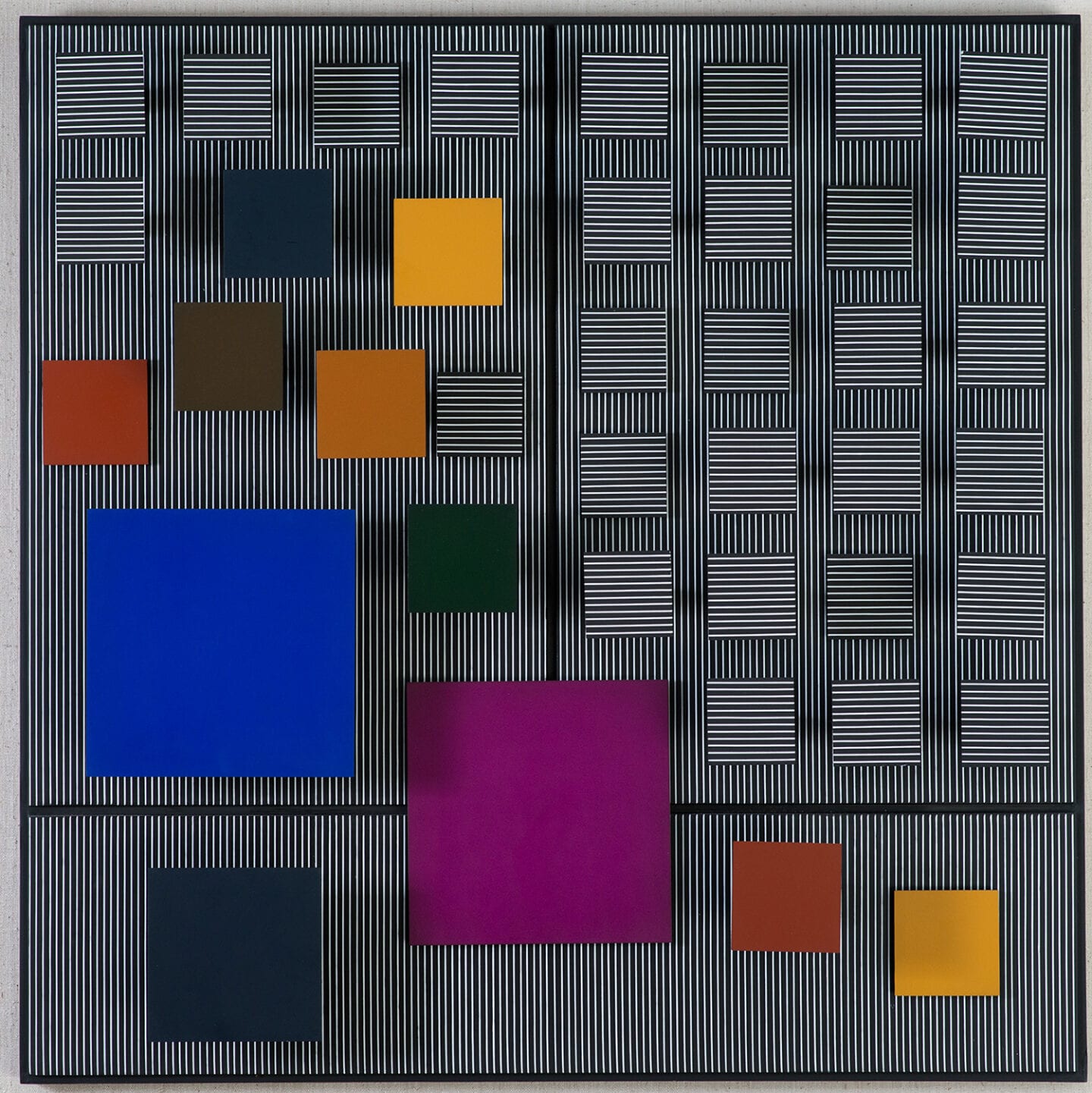

MEGAN: It’s a rare thing of that to occur. Keith was on top of that more than anybody.

NELBA: Oh really?

MEGAN: Oh my god. He embraced that, because everybody was like, what is this thing? And he just took it and went crazy—he started doing this thing of the box within a box within a box—and everyone was like, huh? You know, there was a giant transformation taking place in the world, and they were able to tap into it.

NELBA: It’s intuition.

MEGAN: Whatever the combination is, thank god we had it. For me, it’s exciting. I think it’s motivating for anyone, whether it comes from art or science or literature.

NELBA: In every age, there is something happening. There are the people that have the vision.

MEGAN: Right, and there’s always that collective coming out of art schools or science schools—that mind collective, which is really important, because that exchange feeds everyone else and is so powerful. It just happens. It’s that beautiful human energy that keeps me optimistic.

How did the 80s inspire your career?

MEGAN: I think that became part of my DNA. Only it started young, but I was fortunate to be there at that time. You know, you weren’t really aware of it. When you’re there you don’t really quite know. You just know that you can relate to what was happening and you could contribute in some way.

NELBA: You don’t know that you are going to make history.

MEGAN: No, you have no idea.

NELBA: In Argentina, the 80s was a big alternative theater movement. I was part of that because I was doing theater for 12 years.

MEGAN: I was in Buenos Aires in the 80s because I met my ex-husband, who was Argentinian, at the Mudd Club. And that’s where we all used to hang out. Jean and I would go there and Andy would hang out. We all would be there bouncing off the walls and acting like juveniles.

That’s amazing you got to be such a big part of history.

MEGAN: Yeah it was brilliant. I left New York to study abroad because my father was concerned about me because I was getting a little too wild. He thought, well now it’s time for you to go. So he packed me up and sent me to Florence to study.

THE ART OF THE APPRAISE

So what happened after Florence?

MEGAN: After I studied in Florence, my boyfriend and I decided we would get married. So I went to Buenos Aires, got married down there with him. I ended up working for an Italian that had a gallery who was collecting 16-18th century European art. He had a gallery in Monte Carlo and he had a gallery down there as well. He was collecting art locally and I was cataloguing it for him because his English wasn’t that great. We would take the collection to New York and sell it at Sotheby’s. So I started doing that in Buenos Aires and then I ended up moving back.

When did you officially get your appraisal certificate?

MEGAN: I’ve only been appraising for like three years now, but I maintained my art relationships and people that I know in the arts. And then I got married a second time and my second ex-husband was in the fashion industry. He designed prints on fabrics. His family is Swiss and they also did lace and all that. They have museums and all this stuff, but that didn’t work out either. [laughing]

NELBA: Despite the lace?!

MEGAN: Despite the lace, it just didn’t work out! [laughing] My ex and I would go to Paris all the time to go to the fashion shows. I got crazy exposure but whenever we would go to Paris I would park myself at the Louvre.

NELBA: Of course, why not?!

What is a typical day as an art appraiser?

MEGAN: Being an art appraiser is wonderful because I get the opportunity to dig a little bit deeper into subjects that I may not have that much knowledge about. It’s a constant learning that I love. I did a piece of artwork—it was a watercolor—that we thought was a Turner. It was in a family estate for a couple of generations and it turned out not to be a Turner, but the amount of work that went into trying to figure out the origins of this piece was tremendous, and I just saw more Turners than I ever imagined existed. It was so much fun!

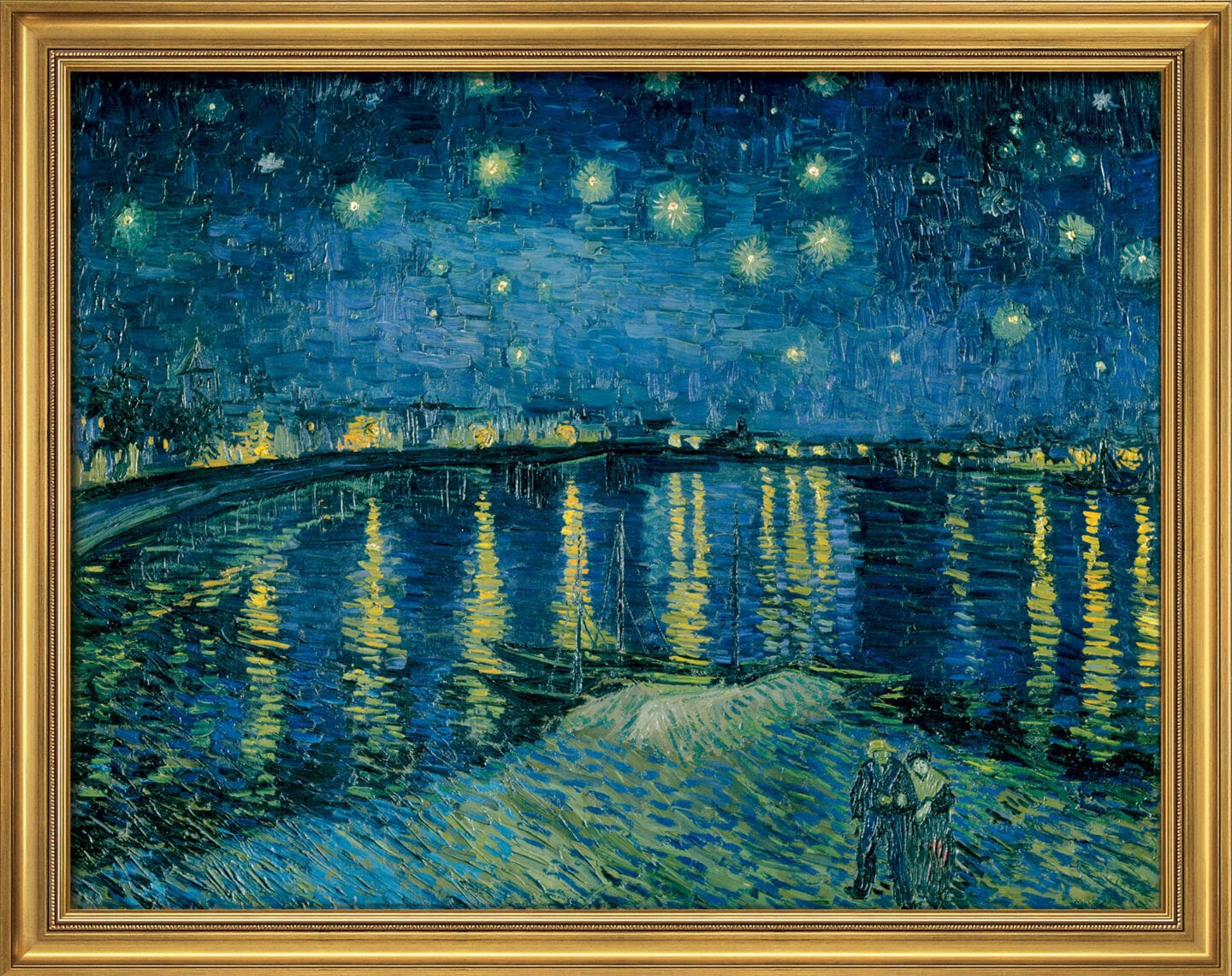

Recently, I actually had been asked to do a Van Gogh, and there are pieces of Van Gogh that I never knew existed. From my point of view, at this stage of my life, to dig deeper into subjects that I thought I knew everything about but learning even more, is the beauty of being an appraiser. It can be very random. Last month I was working on a huge project for Disney. So I mean, from Disney to Van Gogh. I finished a collection of original 45 Disney drawings for animation and film. I have to say it was very sweet, It brought me back to being a child. It reminds me that art is very much alive and some of it never dies.

What is the best part about being an art dealer?

NELBA: One of the best parts of art to me is the research part. When you receive a piece, especially a masterpiece, I have to validate the work before offering it to the collector. Working in solitude with a piece is so precious and so intimate. After you’ve done your research, you can feel the spirit of the piece and feel confident that you’re bringing something you believe in. Many years ago, it was a Matisse that came to my hands. While I was doing my research, I called the gallery in Sweden that supposedly sold it to the current owner. Before offering a piece like a Matisse, you have to be sure it’s real. So I called him and he said: ‘This is the second time somebody has called me telling me about this piece from my gallery. That is not from my gallery.’ Two months later, the FBI rang the bell. There was somebody doing fake documents and invoices, putting the the gallery logo into the header.

MEGAN: We are like the overseers of art. We are making sure there is no abuse taking place. I mean, as an appraiser and a good collector, you’re protecting the artist and the art piece itself—and the person that’s buying it. It’s that whole ecosystem.

NELBA: Oh yes. You’re a protector of the piece and you’re the protector of your collectors.

MEGAN: Even as an appraiser, I love that relationship you have with the person who has the collection—there’s always a great story to be told.

NELBA: They have to trust you in many ways.

MEGAN: Right. For an appraiser and a good dealer, it has everything to do with trust. There are so many hucksters out there.

NELBA: In my case, there’s always money involved. It’s very delicate.

MEGAN: There’s a lot of things that happen in appraising too, though. It’s such a small community — The Appraisal Association — that anybody who does shifty stuff, basically the word get out and nobody will go near you.

NELBA: In our business, it’s the same, because we know each other very well. Auction houses know us, we know them.

As an appraiser, how do you determine the value of an artwork?

MEGAN: There are quite a few things that determine the value of a work of art. That is why I am asked to appraise. Each work is different, no one piece is alike; for many different reasons. One makes reference to libraries, current retail, auction, museums, and galleries including market analysis, ownership, provenance; a multitude of factors. A process that is time and research intensive.

How about to sell?

MEGAN: I’m not allowed to sell the art that I appraise. If I do an appraisal, I’m not allowed to do that because that would alter my opinion. It’s a dangerous place to go. And if I did do something like that, it’s such a small community that I would be shunned. I think there’s only 2,000 appraisers in the entire country. So it’s a small institute. I think it’s becoming more of a demand for people like myself. You go to galleries, museums, libraries. There’s a thing called the Catalogue Raisonné, which has a huge collection of individual artists. And it’s kind of the encyclopedia of each artist and I know people who work for the Catalogue Raisonné. Most of them are PhDs and they study a particular artist and discover every piece they ever made and catalogue it. And it’s like a huge archive. It’s my favorite place to go.

Nelba, tell us about Spotte Art and how you became an independent art dealer.

NELBA: I was working by myself and advising collectors since 2003. I was working with important, expensive pieces. After many years, you develop an expertise: Who has this? Who has that? Who wants to buy? Who wants to sell? But this requires a lot of time. It’s not like you are selling an expensive piece every day. Because of all these years I know many people and artists. It’s funny because the secondary market is very secretive. Nobody wants to expose what they are selling, buying, or what is new in their collection. Everyone sometimes is fighting for the same piece. Spotte Art is totally the opposite. I’m offering emerging artists that I choose. Not expensive pieces, but really good market value and something that is good art. Everyone can have a good collection, but you don’t have to spend a ridiculous amount of money.

THE JAMES BOND MOMENT

What was the most memorable moment of your career?

NELBA: My story was like some kind of James Bond story. It was something so ridiculous. I was at a party in Paris. I’m so bored at those parties and I never belong. Many people were there. Artists, art dealers, but it wasn’t the most friendly environment.

MEGAN: No it’s not. They’re so rude.

NELBA: Right… So I went to the window and I met some guy. He was from Brazil but he lived in Paris, and was as boring as I was [laughing] So we began to talk at some point we exchanged cards. He was the editor of a magazine and I told him what I was doing. We had that exchange in October. By March or so, I receive a call from somebody that said ‘I am looking for a piece by Soto.’ Soto is an artist from Venezuela. Everyone was crazy about him and I had a lot of contacts there so I said, ‘Well I have a piece, but somebody else is looking at the piece so I cannot show you.’ At some point her client asked, ‘What is the name of the owner?’ I wasn’t going to reveal my source, so I told her to tell the client that I’m the owner. A week after, I received a call from the guy that I was at the party with back in October. I was totally surprised. He said, ‘I am calling you because I know that you have this piece and I have a client that was looking for that piece, and somebody told him that it belongs to you.’

MEGAN: Oh, so he was selling it?

NELBA: It was somebody that was selling for him. When they knew my name, he went to the Paris guy. I decided that it was something like a James Bond thing because I had to pull out the piece from Venezuela, which is not easy.

MEGAN: And you protected your source.

NELBA: When he had my name he didn’t want to go to her. He wanted to go straight to me.

MEGAN: He wanted to take her out of the equation.

NELBA: Yes.

MEGAN: He calls you directly.

NELBA: Yes.

MEGAN: Gets her out of the picture.

Because it’s cheaper right?

NELBA: Exactly. He assumed he is going to pay less. The funny part was that it was still a huge amount of money. I had to deal with somebody to send me the piece without paying.

MEGAN: That’s got to be very interesting.

NELBA: Since he didn’t know me, one day he called said, ‘Well I agree on this price. I agree on this and that, but I don’t know you.’ And I say, ‘I understand, but the owner is not going to give me the piece if I don’t have the money.’

MEGAN: Yeah what are you going to do, steal it? I mean you know. Where are you going to go?

NELBA: I said, ‘Okay, there is no other way. You send me the piece, I’ll show the piece.’ I am the one that is backing up the whole operation.

MEGAN: Right. That’s a huge responsibility.

NELBA: But this guy didn’t know me. He knew the woman he was dealing with in the beginning, but he wanted to cut her out of the picture. So I say, ‘Okay, you send me the money and trust me or we don’t do this.’ I remember it was a Sunday morning, and he said, ‘You know what, I trust you.’ So he sent me the money and everything was perfect, but it was some kind of operation because there was lots of coordination to transport the piece. It was a very complicated piece because it was a piece with strings.

MEGAN: Oh it’s a kinetic piece?

NELBA: From the 60s. So many metal pieces, it was so complicated.

MEGAN: I can’t imagine. So you have to organize the transportation?

NELBA: The whole thing.

MEGAN: The price was included in that? Or how does that work?

NVD: If the piece was sold, he was the one paying the transportation. If the piece was not sold, we share.

That’s complicated.

MEGAN: It’s very complicated. It can take years to sell a piece.

NELBA: They sent a French guy to see the piece and when the Brazilian guy saw a picture of the piece, he confirmed he wanted it. So we went to the bank and did the transaction.

MEGAN: With the Frenchman?

NELBA: Yeah, I had the money in my account. I did the wire transfer to the owner, and the following day the French guy and myself went to the collector’s apartment on Park Avenue to put up the piece. Every new piece is such an excitement because after a piece is a huge story.

MHG: Well that’s the beauty of art! That there’s something really spectacular about it.

NVD: Something so unique and different every day.

MUSEUMS, FEMINISM, AND RBG

Do you prefer working with museums and galleries or do you prefer private collection?

MEGAN: I like private collections.

Have either of you ever also sold to museums and galleries?

NELBA: I once bought pieces from the MoMA.

MEGAN: You bought for somebody?

NELBA: Yes.

MEGAN: That’s interesting so how do you do that? I mean, somebody says, ‘Oh I saw this at the MoMA. Can you get that for me?’

NELBA: The owner was a Brazilian guy. I had to go to the backstage of the PS1 at the MoMA when the show was over to see the piece again. It’s so nice because they open everything for you.

So you buy on behalf of buyer?

NELBA: I buy on behalf of somebody. The piece went to the show at the Whitney.

MEGAN: But now it’s more valuable. Once you get to the museum level, it’s like a stamp…

NELBA: Right. You solidify the price and the importance of the piece.

MEGAN: There’s so much! We could do this all day long.

What was the last exhibition you both went to?

NELBA: The last exhibition I went to…Caravaggio.

MEGAN: At the Met?

NELBA: Yeah.

MEGAN: I missed the Caravaggio, but I did see the Dutch paintings downstairs. Did you see those?

NELBA: I did…

MEGAN: Oh. You didn’t like them?

NELBA: No.

MEGAN: Oh, I loved them.

NELBA: I like just the one Vermeer, and the rest I said, ‘What?’

MEGAN: Really?

NELBA: Yeah. I said, ‘what?’

MEGAN: I love Dutch paintings.

NELBA: Me too, but not those. Actually no there were two that were great. But they were so different from each other.

MEGAN: Yeah none of them really spoke to one another but I thought each of them were so brilliant. I mean, I just…

NELBA: No, well, I didn’t like it.

MEGAN: I loved the Vermeers. I can never get tired of looking at it.

If each of you could own any artwork in the world what would it be?

NELBA: Somebody that I love is Anish Kapoor.

Oh I love him.

NELBA: Me too. That kind of precision. I went to the Pérez Museum. Maybe that was the last exhibition that I saw because I was in Miami last week and the Pérez Museum is incredible. Beautiful building. The collection is more or less, but the building is so nice.

MEGAN: Sometimes the buildings are nicer than the collection. I agree. It would take me a long time to make a purchase any fine art. I go for the classics. I wouldn’t mind having a Van Gogh and I wouldn’t mind having a da Vinci!

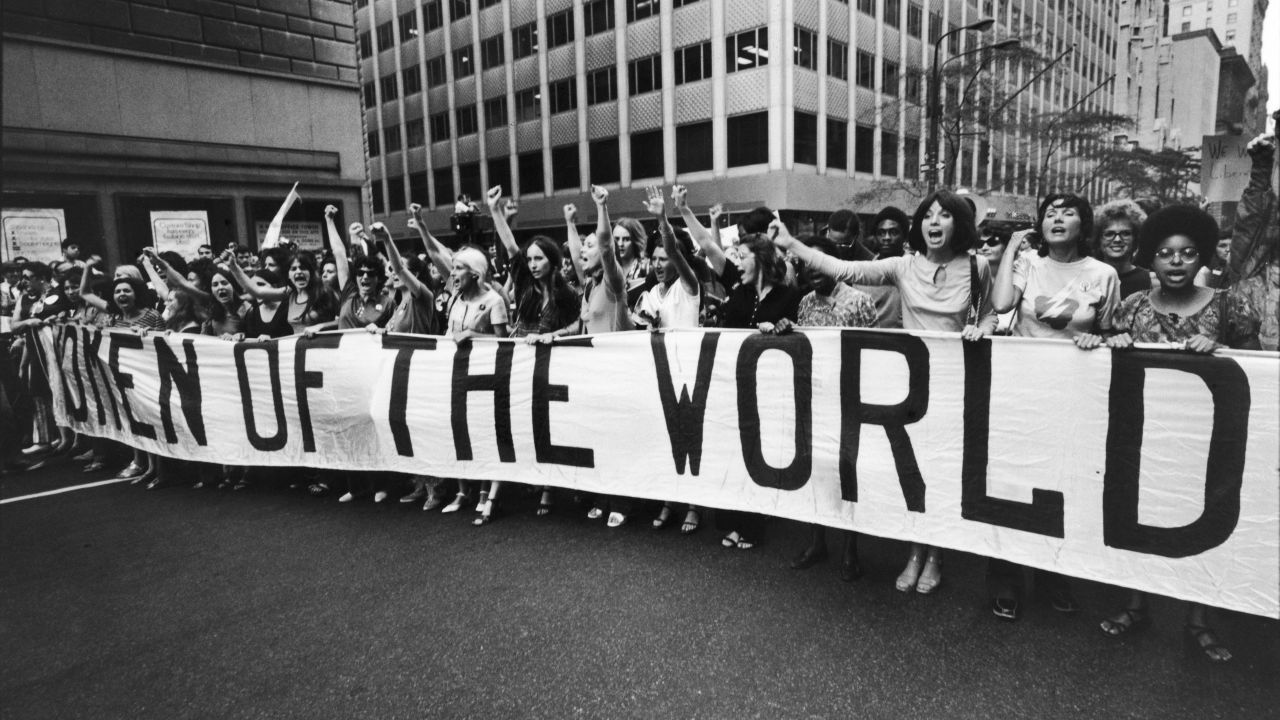

How has the presence of women in the art world shifted in the last few decades?

MEGAN: Oh it’s so much better than when I was in the 80s. I mean, I think the 80s was the beginning of that really. I think women started to really pop out at that point. I mean they were all over the place: Judy Chicago. Cindy Sherman.

NELBA: I think it’s a market where women have been present for a long time in every aspect.

MEGAN: Yeah, but I think better now than ever. Prior to that it was predominantly male. It’s a slow evolution. I also think that applies to people of color. I think that Jean-Michel is a huge event because up until then black artists just didn’t exist in the art world. There were so few.

NELBA: No?

MEGAN: No it just didn’t happen. And we were all like, what’s wrong with this picture, you know? It was all these white guys. [laughing]

Especially in the 70s.

MEGAN: Oh my god. It was de Kooning, it was Johns. I mean, I actually have a portrait of myself that de Kooning did of me, believe it or not.

Really?

MEGAN: That was the established art world that I was very young and part of. When I went to art school, we were the ones that said, ‘Wait a second. Where are the women? Where are the people of color? What’s wrong? How come all these old white guys are like ruling the world?’ I mean, I loved them because they were brilliant, but it was my generation of artists that were breaking down those walls and changing that.

NELBA: And you know, now there are many showing the work of the wives of the artists, like Lee Krasner.

MEGAN: Of course not like Pollock. They overshadowed. The men were the dominant and it was in the 80s that the walls started breaking down. Women just didn’t pursue art as a career—women didn’t pursue a lot of things as a career. My mother’s mother was a suffragette. I come from a bunch of lunatics [laughing] she was a rebel but she still had these social restrictions. So it’s a slow breakdown. It’s been a process that’s taken a long time and I think anything that has any value always takes time.

NELBA: I always was so rebellious. I remember when I was 17 I went to work in an office and I was in Argentina. I wore pants to go to work. So I remember my boss called me. He said, ‘What are you wearing? Pants?’ I say, ‘Why not?’ Because we were there in the morning very early. It was so cold. [laughing] You know – it was just because of a practical thing. We were cold and it was the time of the miniskirts.

And which job was this?

NVD: It was a whatever job. It was a government office. So I said, ‘Why not?’ And he said, ‘Because this is not allowed.’ I said: ‘Tell me where. It is not written anywhere.’ So he couldn’t say too much. I was the one that established that we would wear pants.

Was this in Argentina or New York?

NELBA: Argentina in the 70s.

You started the pants revolution in Argentina!

NELBA: I did, I did.

MEGAN: So then did everybody start coming to work in pants?

NELBA: Yes of course, because everyone was freezing.

MEGAN: It’s a practical matter!

NELBA: I identify with RBG. In the documentary, she said, ‘This is my way to fight.’ To me, you fight everything in a small way and smart way. You can make small contributions that make a bigger difference, or you can shout and spend a lot of energy in protests and marches, which doesn’t go anywhere.

MEGAN: Right. Nothing happens. It’s increments.

NELBA: But if you put things in their place every time they happen…

MEGAN: It comes together.

NVD: It comes together–and you help the rest of the world, too.

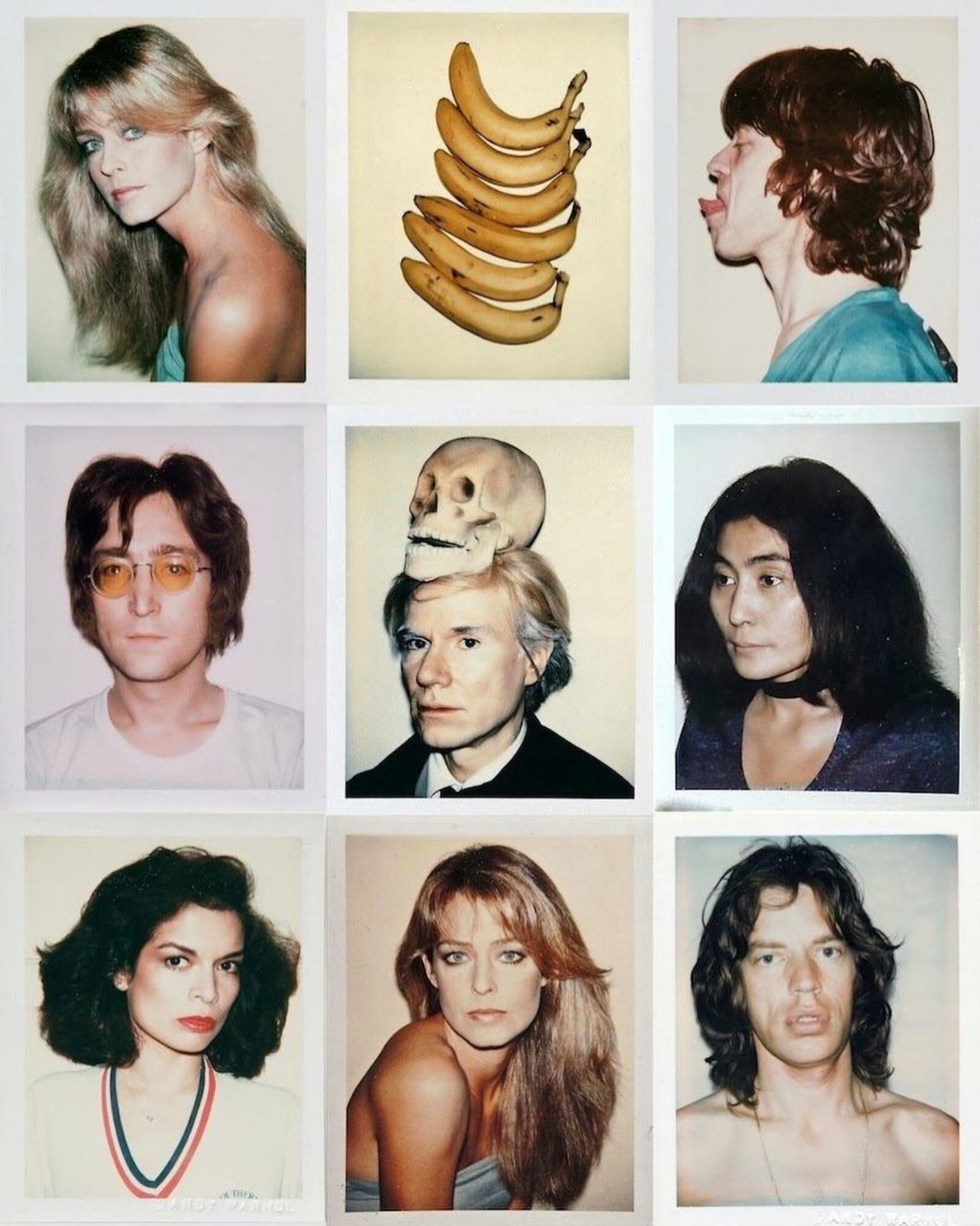

Top Image: Andy Warhol, ‘Pat Hearn.’

Megan Hay Guglielmo is part of the Appraisers Association of America, and Nelba Valenzuela-Delmedico is an Argentinian art dealer and owner of Spotte Art.