Dóra Maurer: Art From the Underground

Avant-garde artist Dóra Maurer’s year long, free exhibition at the Tate Gallery, is evident of the social and political effects of the pre and post fall of the Berlin Wall on art.

In 1956, students in the Hungarian capital of Budapest marched against Soviet-imposed policies. The march became nationwide, leading to the Hungarian Uprising, which saw the deaths of around 3,000 civilians. The revolution was ultimately crushed by the violent suppression of pro-Soviet forces. However, this failure resulted in the birth of a new conceptual avant-garde movement, which fuelled underground art circles in Budapest. Mayhem on the streets was the inception of resistance art, found only in cloaked apartments. Among the generation of Hungarian neo-avant-garde artists that emerged in the 1960s, was Dóra Maurer, who has been given her first ever UK solo exhibition at Tate Modern.

The free exhibition displays some 35 works that span five decades of Maurer’s life. The work is incredibly diverse and one feels they can sense the ever changing political and social turbulence from the socialist state to post-Berlin Wall. Graphic works, photographs, films and paintings all elicit Maurer’s statement that her art was ‘an object of actions in continuous chance.’

As historians and curators Maja Fawkes and Reuben Fawkes have argued, Hungarian authorities held control over the “mechanisms of artistic productions and display.” The authorities would treat any experimental art by “wavering between banning and tolerating” them. Although galleries were frequent in Budapest, they were heavily influenced by state ideology. To get any work in a gallery space, artists had to apply to The Ministry of Artists Association. Unsurprisingly most experimental artists, or any that appeared anti-state, were denied entry. With no access to a studio space, Maurer took part in spontaneous group actions at a disused chapel in Balatonboglár, which became a hub for conceptual art and political discussions. The chapel was closed down by the authorities in 1973.

When she did gain enough credit to create exhibitions, Maurer would invite those artists accepted by the government, so as not to get into trouble if they came to light. Given these obstacles, Maurer never had a studio, which could be easily suppressed. Instead, she always, and even to this day, works from home. Images visible at the exhibition, taken by Maurer’s husband, architect Timor Gayor, show the artist working in her own kitchen. To create such works in a utilitarian kitchen sink environment, hinted at the presence of a personal freedom, uncontainable by state ideology.

Movement, uncertainty and chance were prevailing themes in the Hungarian public discourse. The fall of the Soviet Union was on the horizon, yet most acted as if the union was stable, in what Adam Curtis coined ‘Hypernormalisation.’ Having a dual citizenship, Maurer was able to commute between Vienna and Hungary. She wrote that in Budapest many people were active at a time when there was an “ambitious movement… more stimulating than the fixed, balanced art scene in Vienna.” It’s the ever changing social environment of Hungary that created so many experimental artists. Many commentators have stated that it is a testament to chaos that so many artists’ works lost impact when the fall of the Berlin Wall brought social stability.

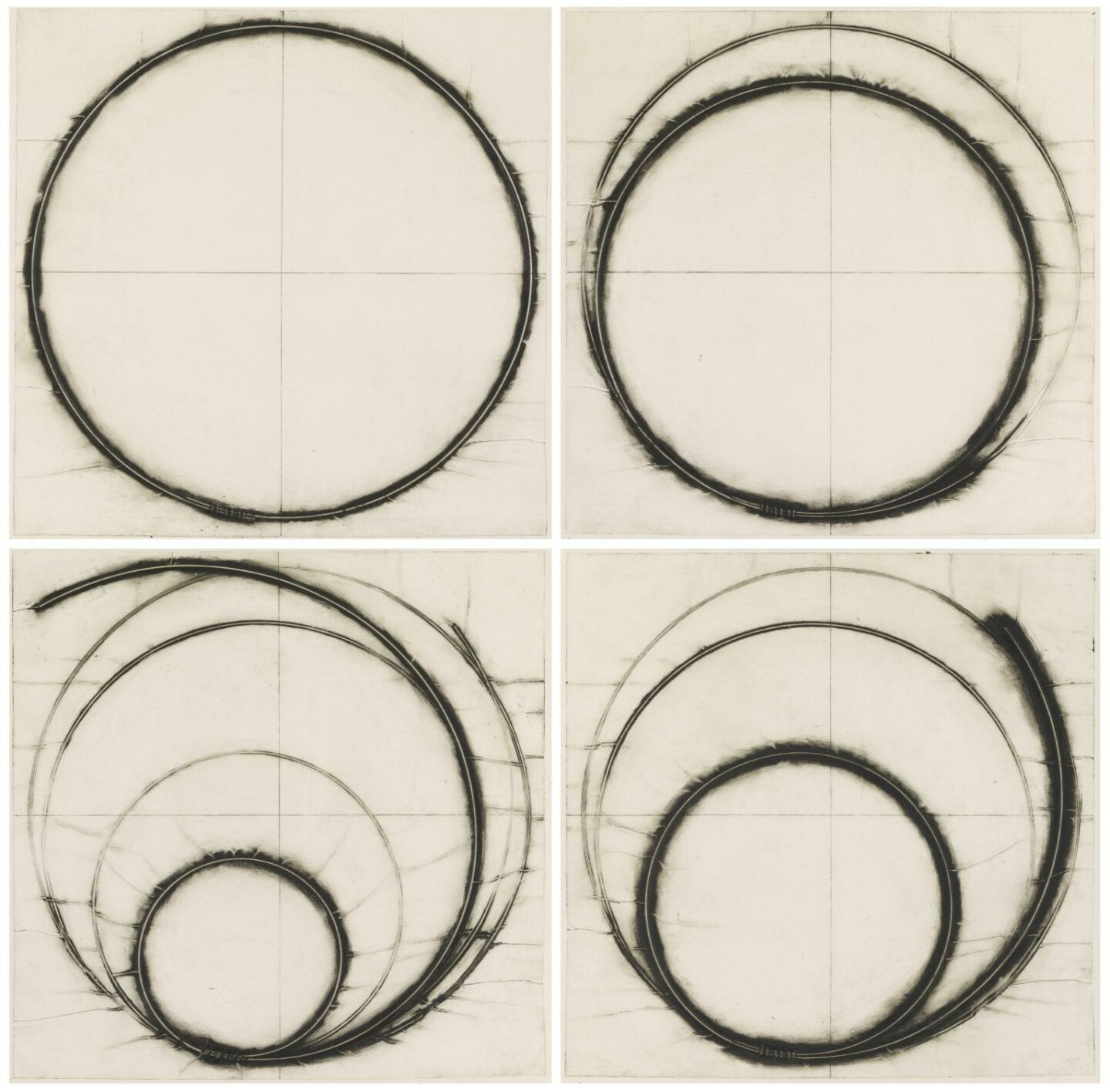

In 1972, Maurer placed three strips of paper on a busy Budapest street, photographed over the course of a day, the bustling footsteps disrupt and trample the parallelity of organisation. The subject is pure chance, with the Hungarian public as co-creators in both the art and their own environment. This is what Maurer called ‘action graphics,’ not focusing on an image but something that happens with the materials, or tools. Maurer wrote:

“I did not regard these photos as images, but as signals that can easily be interpreted.” — Dóra Maurer

A single image is not enough; but a sequence allows you to trace human intention. The works although exploring time and space, were deeply political. A trampled piece of paper, was evidently a critique of the simulacrum of social solidity.

During the late 70s, Maurer began working with moving images. At the exhibition one can watch Triolets 1977/1981, A short film that shows three levels of different human faces; the mouth, eyes, and forehead, or as Maurer stated; the earth, middle, and the sky. The faces move side to side, and allows the viewer, by chance, to construct different portraits. Accompanied by a layered vocal glissando, the face is slowly formed together, like the chaos of a puzzle finally being solved. The majority of Maurer’s work presents the viewer options and then deconstructs what the viewer can do with those options.

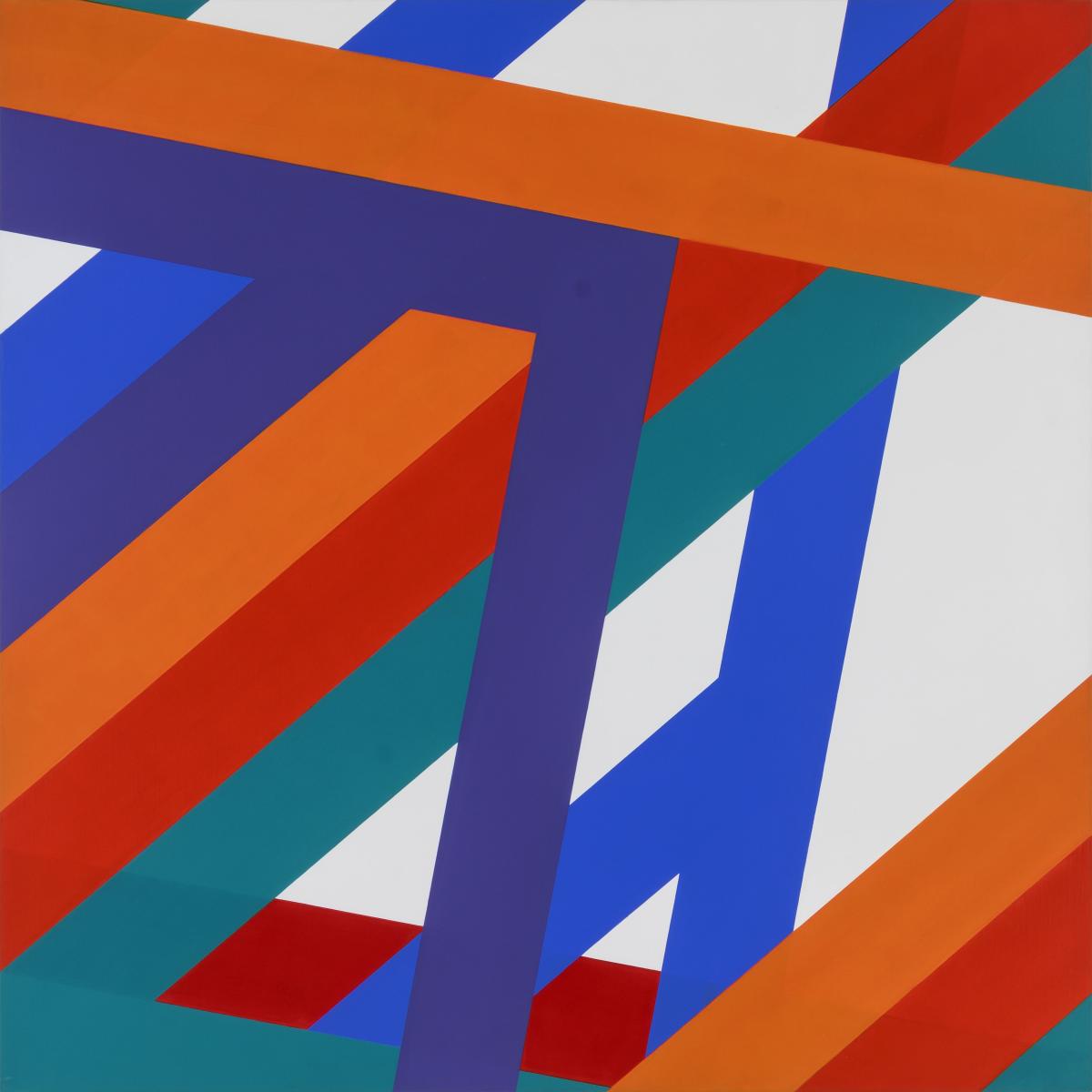

As one reaches the end of the exhibition, the Cold War was reaching its finality. Yet for the first time, Maurer’s work isn’t depressingly evident of her social surroundings. The room is bright and idyllic with what Maurer called “space paintings,”, acrylic installations of overlapping colour that disregard the conventionally curated space. Each canvas is flat, yet influenced by the colour theory of Josef Albers, there is an illusion of three-dimensional mobility. The room is filled with bright murals of parallel and intersecting lines that transcend corners and ceilings. Arguably, it isn’t Maurer’s best work, but it certainly evokes a better present moment in our society, no matter how questionable that may be.

Dóra Maurer is now a professor at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Budapest, and a curator. ‘Dóra Maurer’ is a free exhibition running at The Tate Modern in London until July 2020. Featured Image: Dóra Maurer, ‘Seven Twists I-VI’, 1979. Image Courtesy of Tate.