We visit the Swiss art dealer’s Upper East Side gallery to discuss the global art market and building an international powerhouse.

Swiss art dealer Dominique Lévy has mastered the art business and created a global empire. With a career spanning almost three decades, the 52-year old businesswoman has one of the most impressive resumes in the industry. From being hired by Simon de Pury to work at Sotheby’s in Switzerland, to getting headhunted by François Pinault to create and lead the private sales department at Christie’s, to co-founding a gallery with Robert Mnuchin, and then founding Dominique Lévy Gallery in 2013. By 2017, Brett Gorvy, the former chairman and international head of post-war and contemporary art at Christie’s, joined forces with Lévy and her gallery became known as what it is today: Lévy Gorvy, an international powerhouse that has expanded from New York and London to Zurich and Hong Kong.

Unlike most galleries in New York, Lévy Gorvy is located in a historical red brick building on Madison Avenue originally built in 1931 for Fifth Avenue Bank. “All of our galleries have a soul,” Lévy says. Known for its critically acclaimed museum-quality exhibitions such as the “Calder / Kelly” or “Warhol Women” show, the gallery’s mission is to have a diverse roster of artists that create a space for meaningful discussion and conversation. Upcoming shows include a special duo exhibition with Yves Klein and Agnes Martin, and a solo show featuring Mickalene Thomas in the fall.

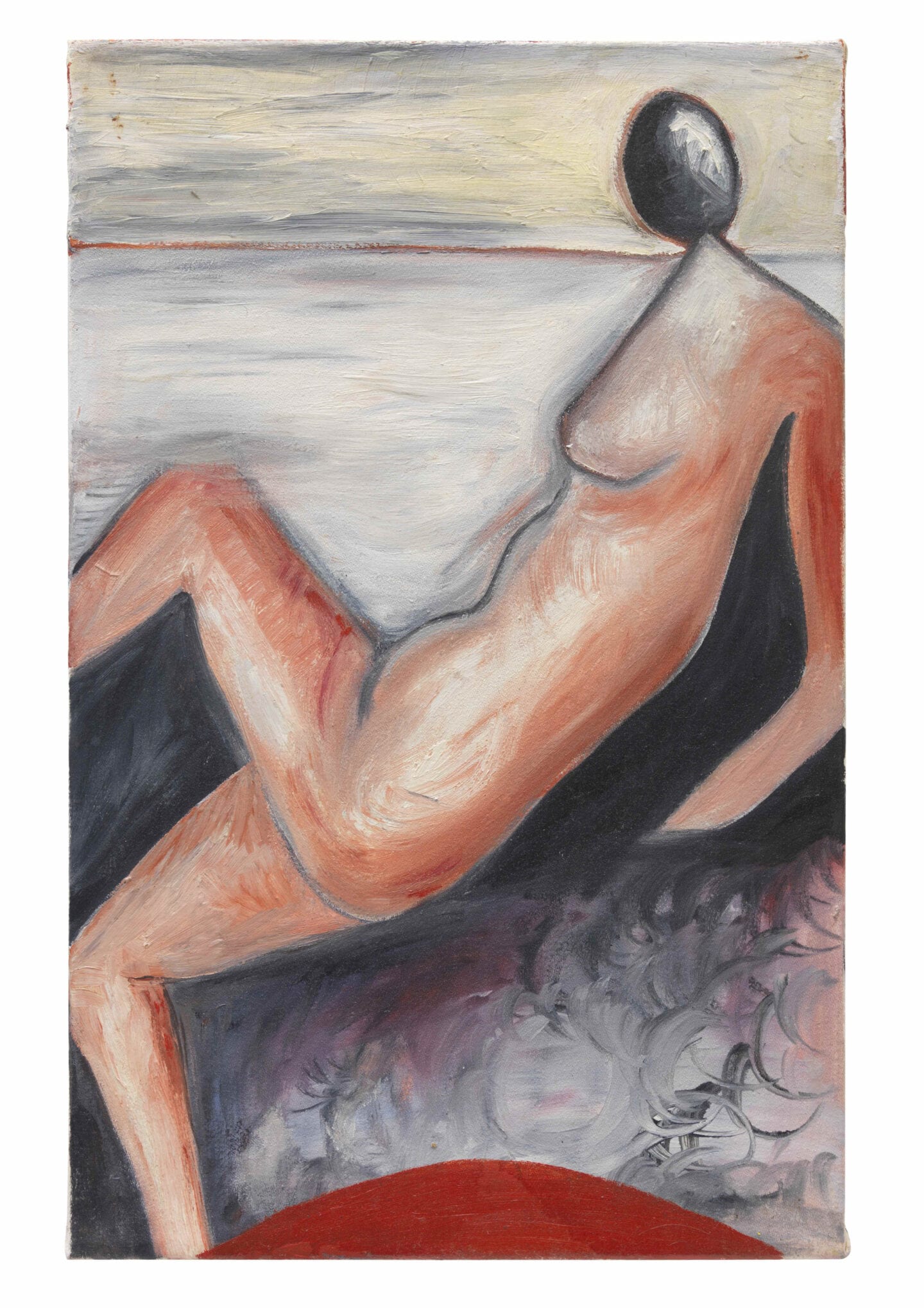

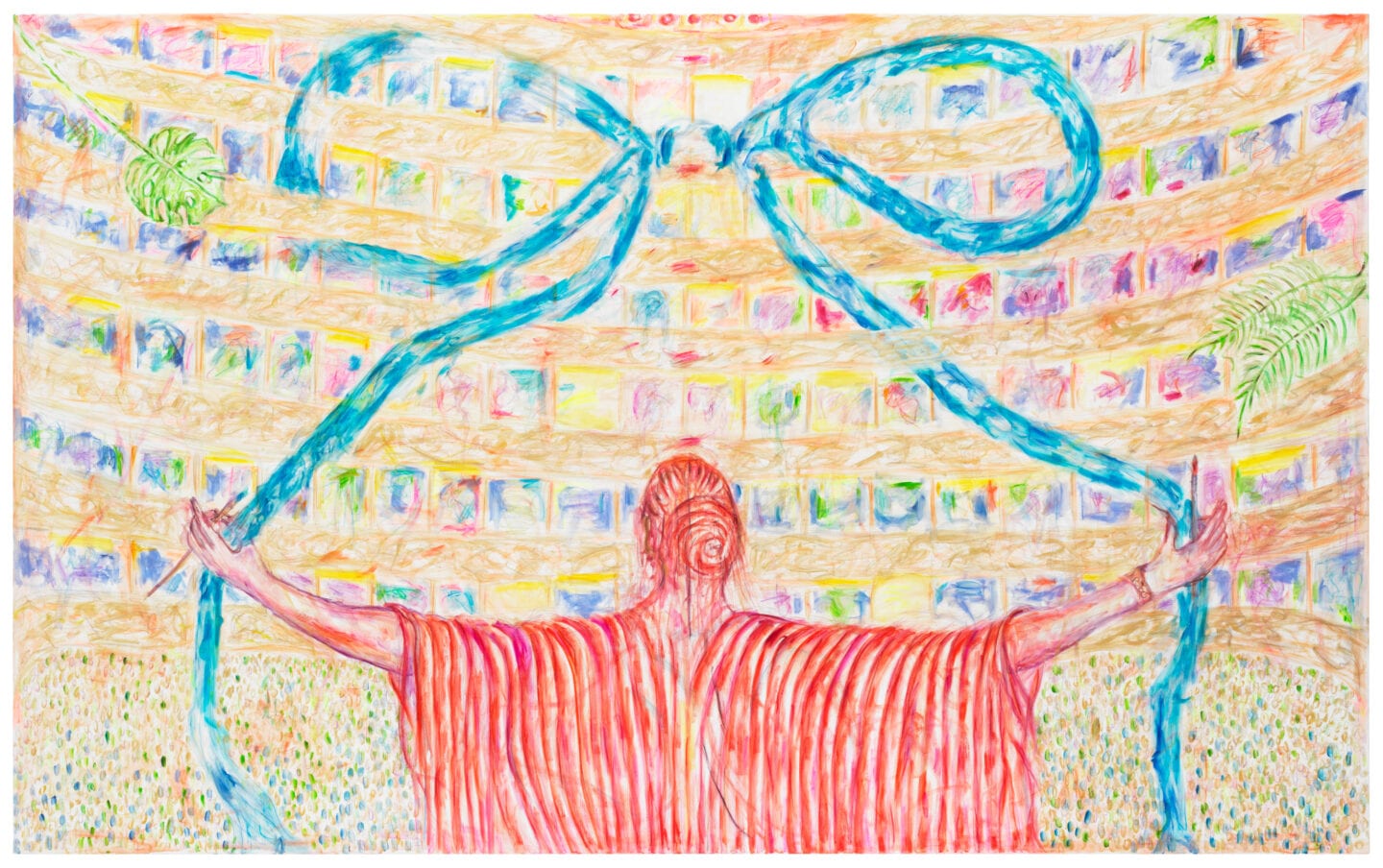

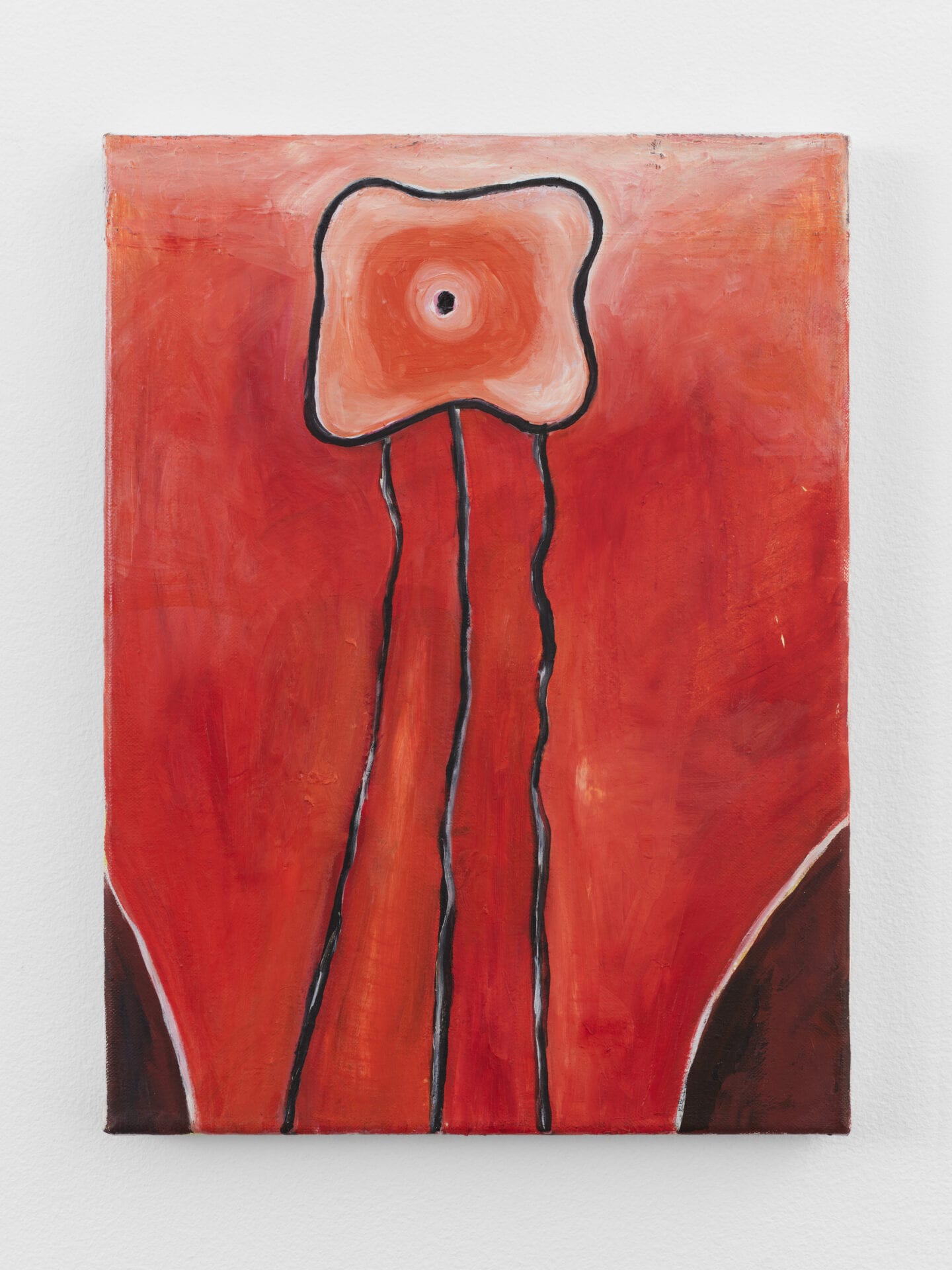

Lévy Gorvy’s current exhibition features Jutta Koether, a German artist whose work mines the discourses that shaped Cologne culture in the 1980s as well as those she encountered when she moved to New York in 1991, constructing an eclectic artistic genealogy that runs from early-modern perspective painting through Symbolism, Post-Impressionism, and Surrealism, on view until April 18th.

“I believe as an art gallerist you are a wanderer. There’s a great poem by Antonio Machado and it says something like: ‘There is no path, the path is made by walking.’ And at the end of the day as a gallerist, that’s my core mission.” — Dominique Lévy

How did you begin your career in the art world?

I wanted to be a theater actress. I went to Paris and I was spending more time looking at art. I grew up in a family of collectors and particularly for my mother, art was like a breath of oxygen in Switzerland where a lot of things are rigid and stifled. Very soon, anything to do with art and artists was stimulating, energizing, puzzling—all these tumultuous emotions. Although I studied theater and political sciences, I feel I was raised and fueled to be in the arts, and whether it was being involved with a dance company or theater company or working with artists, it had to be with creativity. The turning moment was at the end of my political studies. I met a teacher who was in Paris teaching art sociology, and that blew me away how the artists were a pulse in expressing in different ways what was happening and being told about. I fell in love with an old building and I did an exhibition with such a quirky ridiculous name at the time in French called “Artists of Today in Yesterday’s House” or something like that. I was twenty-one and I invited all these artists to make installations in this old 18th century house—and I knew I’d found my place, there and then.

How did you go from Dominique Lévy Gallery to Lévy Gorvy?

After I settled in this building, 909 Madison Avenue and created Dominique Lévy Gallery, I knew within the future I wanted a partnership and I knew I wanted to work with Brett Gorvy, since we had worked together at Christie’s 20 years before. It happened very organically through conversation and realizing we had common ethics, common passions, and common taste. We may go at the business in a very different way—we are very different individuals—but our core values are the same. And so we merged.

Describe the mission behind your gallery.

I would say the mission starts with creativity and love. I live with this wonderful quote from Deepak Chopra on my desk, and it says: “Love without action is meaningless and action without love is irrelevant.” I think what we do is very important and seminal because showing art, allowing artists to express their best self, allows the world to be a better place. And therefore the core mission of this gallery is to be art centric. Not artist or client or museum-centric, but art centric. Art is as important to me as any kind of science or any kind of other profession. It’s not a side job for people who have money, which is often what we hear. I think creation and creativity are essential in anyone’s evolvement. If you look at any artist that’s above 80, they’re more agile, more creative, more generous, than any lawyer or banker above 80. That tells you a lot.

“I refuse to say ‘woman gallerist,’ ‘woman dealer,’ or ‘woman artist,’ because I’m a gallerist. I’m a dealer. My artists are artists. You don’t talk about a man painter so I’m not going to talk about a woman painter. I try to fight this. I don’t want this to be a defining factor for quality.” — Dominique Lévy

What is a typical day for you as a gallerist?

There’s no such thing. Every day has its good moments, difficult moments, challenges, discoveries, urgencies, time to create, time to think. I really think there’s no typical day. It ranges from in-house meetings, to artist meetings, to exhibition design, to books, to writers, to finding works of art, selling works of art, buying works of art, looking at what is around and what colleagues are doing, and to be interesting and engaging in a creative world.

“The art market is an enormous study which comes with experience first—nothing can compete for the years in this market because you’ve seen first-hand how it changes up and down… I think the issue with today is you have 80% of unknowledgeable market makers, and 20% knowledgeable market makers.” — Dominique Lévy

What resources do you use to keep up with the art market trends?

I’m more focused on market value. I don’t like trends, and I’m absolutely not interested in trends. I refuse them and I fight against them. But market and understanding value of art is sometimes a trend and it involves a lot of understanding about taste, region, where are the buyers from, and what are they looking for now, and what is indeed trendy, what is overvalued, undervalued, what is serious, not serious, what has legitimacy, or not. The art market is an enormous study which comes with experience first—nothing can compete for the years in this market because you’ve seen first-hand how it changes up and down. Databases—today there are multiple, whether it’s Artnet or Mei Moses—things like that. And then really knowledge of the art. I think the issue with today is you have 80% of unknowledgeable market makers, and 20% knowledgeable market makers. And the difference is just the eye and the art knowledge. People look at Artnet and tell you a Picasso from that year is worth this. But then if they really were to look at the painting versus another one from the same period, the same size, it’s two different stories. And so you have a side market that is quite trendy, as you would say, but it’s far from the real market. The real market needs real art history knowledge, plus, market knowledge.

How do you pick an artist?

That is a very thorough and organic process. You have what you like and dislike, what you love and what you don’t love, what you know and what you don’t know. You want your program to have a certain diversity but still coherence. You don’t want to have quantity—at least for me—some galleries love quantity but we don’t. Therefore, you want to have an approach where you feel an artist has consistency and a really trained practice, and consistency in questioning and renewing. We don’t work with unknown artists who are just beginning—this is not our mission. We work with established artists who we try to bring to the next platform and the next level. We try to take artists who we really wholeheartedly believe in. We really feel by being fostered by us, they’re going to be nurtured and nourished and they’re going to become the best of themselves. I believe in relationships and love relationships. A relationship is valid as long as you give the best of you and you see the best of the other. I think with an artist, it’s the same. I tend to be drawn to artists who are very engaged, very opinionated. I tend to be drawn to painting and sculpture more than video and installation. I tend to be drawn to artists that are very generous and idealistic. Artists that see large. Artists that have an incredible freedom even if that is against the market and will not let the market frazzle them. I tend to be drawn to rigor, and the right mix between rigor and complete fantasy, and freedom with extraordinary discipline. I take the artist where the tension is through history, where’s there’s polar opposition, and you bring them together. A centered meaningful practice.

Differences in taste from collector base in New York, London, Hong Kong, and Zurich?

There is not much difference. We are in a global market. What is different is the relationship with collectors. You relate very differently with an 80-year old Zurich collector than a 25-year old new tech Seattle collector. They’re both as extraordinary, but there’s a different relationship, different history, different approach. What’s different is not the taste and it’s not what people want. It’s the history. New collector versus old collector, European versus American versus Asian. The people are different.

With online sales becoming more popular, how is the gallery world changing?

It’s changed tremendously the last five years. It used to be that the gallery is the most important place for a collector because a collector understood that you couldn’t collect an artist without seeing a real exhibition, that you wouldn’t get the best access without a real conversation, that you wouldn’t be in a relationship if you don’t buy and sell and grow with your gallerist—and the best collections have been done with gallerists and collectors hand in hand. In the last five years the auction houses have taken a new level of the market and the artists have taken a much more commodity market. But it hasn’t changed our core mission. Our core mission is still to display art in the highest possible quality that we can. The same commitment, the same core mission. It’s just more hectic, it’s more often superficial, and of course you know—we’re selling art on Instagram, sometimes, but not as much. For the kind of art we work with, it’s not what Artsy or what some of these platforms do. It’s one thing if you’re selling print and if you’re selling furniture—I buy all my furniture on the internet, you know. I know furniture so well and I know the dealers that I can absolutely go on 1st Dibs and find extraordinary things if I want to furnish an exhibition or a house. Unless you really really know the artist—why not? I recently bought something from an artist I really knew on photograph.

“Unless you know very well what you’re doing you should never buy art without standing in front of it. Because that moment, that magic, that emotion, that surprise—you have to be there.” — Dominique Lévy

Tell us about your personal art collection. What are some pieces that we could find in your home?

I’m very private with my art collection but it is built on the question of the self and the theme of identity. I was very interested in how you define your man artist or woman artist or American artist an English artist. And then it grew to works that I find challenge me. I quite like angst in works, so I have works by Arshile Gorky or Mike Kelley or Picasso that have a lot of angst. Sculpture by Rebecca Warren or others that are tough to look at. Even works by Hans Bellmer, Cindy Sherman—they’re all dealing with that kind of—I don’t want to say they’re dark, some are dark—they’re more about humanness and the human condition. And I’ve gone to abstraction—I collect the work of Julie Mehretu, she deals with displacement and identity in an abstract way. I’m passionate about ceramics, I collect clown shoes, I collect 20th century furniture, it’s all a way of living with creative objects that really—even if you look at my office from crystal to Franz West: every object there is a significance for me part of my constant search. I believe as an art gallerist you are a wanderer. There’s a great poem by Antonio Machado and it says something like: “There is no path, the path is made by walking.” And at the end of the day as a gallerist, that’s my core mission. I want to be surprised, I want to learn, and I want to share that. Collecting is not to me an activity, collecting is a way of living. Completely.

A little birdie told me you’re also a ceramicist and you created ceramics for the staff show.

Yes! I took my courage and I decided I’m going to lead by example. I started being a potter two years ago. I’m far from a place where I feel like I could show, but at the gallery it was different. It centers you and makes you see a lot of things differently.

Name your favorite female artists.

Jutta Koether—of course I’d say that, because she’s here. Jana Euler. Amy Sillman—very high on the top. Charline von Heyl. Of course I admire Pat Steir, to me she’s very current. I’m drawn to a lot of women artists because we show them a lot. I love Rebecca Warren because as a woman she decided to become a sculptor, and it’s not a place that’s obvious for women. I’m passionate about Vija Celmins, I’m passionate about Agnes Martin, I love Eva Hesse, I love Louise Bourgeois, and actually I realized my first buy was an early photograph by Claude Cahun. She’s the first one who dealt with the self. Extraordinary woman. During the war and right after.

That’s quite a long list.

I’ve been at this for more than 30 years. If you give me two more minutes then maybe it would be doubled! I don’t have a favorite, you know. As a collector and as a gallerist, I want to say that if you were to ask me what’s your favorite ceramic, when I wake up when I brush my teeth when I go to bed and all in between I would have come up with ten different ones. It’s more what I’m interested in. I’m interested in textures, I’m interested in colors. I’m interested in shapes, I’m interested in a multifaceted approach. Pat Steir, for example, is a painter yes. But she’s also a performance artist and the way she engages with the painting she’s a profoundly conceptual artist. How do you reunite all three? There’s never one reason why I collect an artist or choose for an artist at the gallery. There always has to be a discussion that we can be there tomorrow morning talking about Pat–and that would be the answer of why I love her work and why I’m committed to her work. If I can tell you in ten minutes why this artist? Then it’s not an artist I usually would be showing.

You like artists that spark conversation.

Yes. I think every great artist in history from the first frescos to today, spark conversation. My goal today as a 20th century gallery is to discuss the relevance of that conversation. I love exhibitions that have pas-de-deux. We did the beautiful Calder / Kelly show, all these dialogues of the exhibition to me make everything we do more relevant.

What is some business advice you can give to other women entering the art business?

It’s hard as a woman. And it’s not discouraging advice—it’s just, brace yourself. Because I have found that being a mother and being a business woman makes that business particularly difficult. Travel, late nights, weekend work. Particularly difficult. However it’s the most beautiful job ever and I wouldn’t change it. For business advice I’d say never believe in certitude. I think a lot of the galleries are building programs on certitudes and I think it’s one of the traits of a woman not to have certitude. We see it as a weakness, I see it as a strength. Embrace your vulnerability—that’s another strength in this business, because it allows you to choose better, to look better, to feel better. Then on a pure business way I would say curiosity, knowledge, and financial savviness. Understand currencies. Essential. Watch what’s happening in the world and the economy. We are linked with all of this. Curiosity and knowledge, enthusiasm. Instinct. But vulnerability is the key.

Who are some art dealers or gallerists you have looked up to throughout your career?

Peggy Guggenheim for sure. Xavier Fourcade and Pierre Matisse. All those other ones I never met but look up to. And the ones that I’ve met: Ernst Beyeler, Marian Goodman, and Paula Cooper. Those are people who I have great respect and admiration for beyond words.

Do you believe the art world is still a boys club?

Unfortunately yes. Not as a criticism, but as a reality. The army is a boys club, the finance world is a boys club, the cinema is a boys club. I believe every world is a boys club. I have two sons and good for them. I don’t see this as a minus, I see this as a simple reality. The only place where it’s a minus is for artists. I’m worried because now the pendulum is going the exact opposite. If you’re a woman suddenly you’re better than if you’re not a woman and that’s dangerous. I think that there’s a lot of risk for patronizing or compromising even mediocrity if you start thinking that we need to give a chance because you’re a woman. No. However, if you’re as good as any other artist, you should have as much, not more, but as much possibility as a man. And I think it’s very difficult. I refuse to say “woman gallerist,” “woman dealer,” or “woman artist,” because I’m a gallerist. I’m a dealer. My artists are artists. You don’t talk about a man painter so I’m not going to talk about a woman painter. I try to fight this. I don’t want this to be a defining factor for quality. I have two boys but if I had two girls I would raise them exactly the same way. But of course it’s a boys club.

What has been the highlight of your career?

I’ve had so many highlights you know. I’m so blessed. I think the highlight of my career was being able to go against my family and against everything I was raised for to embrace my passion. And I have the same emotions whenever a book we publish comes out or whenever we open an exhibition or whenever we open an art fair. I don’t think there’s one highlight. There’s a few moments that maybe have been transformative: going into Jasper Johns‘ studio and bursting into tears because of the magnitude of the man in the work. Or having dinner in front of Ellsworth Kelly or Vija Celmins—these people who I have so much admiration for. I think the highlights have mostly been the connections with the artists. But then it goes beyond.

“A relationship is valid as long as you give the best of you and you see the best of the other. And as soon as you have to compromise you have to question it. I think with an artist, it’s the same.” — Dominique Lévy

What is the biggest lesson you’ve learned?

To never be sure of anything.

What is your philosophy in life?

Present moment, wonderful moment.

What tactics have you used throughout your career to empower yourself and to lead as an authority figure?

Trying to inspire, desire to excel, bringing knowledge, enthusiasm, and energy in what I do. Admitting vulnerability, definitely. And where I think I’ve often failed is because of the pace of where we live and the necessity of doing things fast, often I forget to listen. It’s hard to listen when there are many voices—you lose time and there is such a lack of time.

That’s true. We are living in a space where there’s so much stimuli.

There’s no place to filter. And more and more I’m just going back to the original place which is the instinct. I’m trying to learn to say no. To myself first and foremost.

What can we expect from Lévy Gorvy the rest of 2020?

It’s a strange year. I think what’s happening out there in between the different political situations, the health situations, the climate worries, I’m hoping that we are going to expect that less is more. I want my teams to be healthy, productive, and mindful. You are going to expect a few less exhibitions and a few less art fairs, but the exhibitions will be longer and the art fairs will be better. And hopefully, which has always been what you can expect here, a place where you find interest, conversation, and discussion: where you feel that you are learning something and at least feeling something. That’s really the goal.

Featured image: Dominique Lévy in front of Jutta Koether’s Pink Ladies 2 (2019). Photography: Lucas Hoeffel for ART SHE SAYS.