Young In Hong: Exploring Forgotten Communities

Two years after her participation at the renowned “Korea Artist Price 2019” at MMCA, Korean born and Bristol based artist Young In Hong is holding her first exhibition at PKM Gallery, unveiling a powerful multi-sensorial narrative through large-scale embroidery work, sound installations and photo-score series.

In her art practice, as well as in her ongoing show “We Where”, she investigates forgotten communities, approaches to individual and collective history, and questions of equality and boundaries: all themes of highly importance today, which we may call political, as in, they question the existing orders we are living within.

Artist as well as academic, Young in Hong work approaches complexity in a compelling and poetic manner, capturing the viewer in an aesthetic experience which politely suggests to look beyond or within an artwork, and question the world around us.

In her interview, she dives deep into the leitmotifs of the exhibition as well as of her whole artistic practice and career.

“For me, equality is not about a = b, but rather more about recognising the space between a and b, which allows us to further explore the relation between the two…a space that opens up the opportunity to become the other.”

Young In Hong, Colourful Land (An Homage to Robert Morris), 2021, Felt fabric, metal chain, and earring hooks, 430 x 25 x 240 cm (c) Courtesy of the artist & PKM Gallery

Your current show at PKM gallery exhibited 8 of your new works and concentrates on the topic of “communities” with a special focus on forgotten or marginalised ones. Could you tell us more about this concept and briefly about the artwork presented at the show?

While working for We Where I tried to investigate the forgotten and underrepresented communities of our time. I thought about Confucian and folkloric communities in the past where symbols were a crucial means to represent their community’s collective lives. When re-structuring those symbolic images and meanings in One Gate between Two Worlds, I looked at animals, particularly gorillas and monkeys who collectively live and communicate in ways that humans cannot fully understand. My long-term interest has been generating a new community through art making and looking at specific rituals interwoven with the psychological dimension of current society. In my more recent work, ‘community’ becomes multi-species beyond humans.

In the next room, I introduced a new sound installation Thi and Anjan, where I collaborated with a female straw weaving community who work collectively and try to sustain the culturally undermined practice of straw weaving. My interest in community building and it’s notions are often to do with underrepresented cultural practices.

Your work presented at PKM spans across a multifaceted macrocosm of materials and techniques from embroidery to physical and sound installations. You mention William Morris as an inspiration, what is your relationship with your choice of materials, but also with materials themselves?

I learned classical music when I was young, later trained in traditional sculpture and then studied fine art. After my studies, in order to sustain my international career, working on textiles provided an efficient way to exhibit, travel and produce work because they are foldable, light weight thus easy to carry with or store. Perhaps the interdisciplinarity of my work was a natural consequence of my educational backgrounds as well as the nomadic pattern of working and exhibiting in my earlier career.

I’ve been even more interested in craft recently, intentionally working with craft people while continuously learning those skills through collaborations. The textile crafts I do, do not require highly difficult techniques. Craft is a sharable language because its skills are accessible and therefore represent a more shareable language with broader audiences. There is pleasure in the process of making too because the outcome is beautiful.

I sympathise with William Morris when he saw the ideal form of art from the middle ages and its communal values. He was an interdisciplinary artist as well as a craftsman always questioning the existing structures of society.

You asked about my relationship with the choice of materials. I improvise materials. I don’t choose them. If you meant mediums, I work mainly with textile methods, sound and performances. They are often starting with research-based processes ending in different or combined mediums.

Young In Hong, A Colourful Waterfall and the Stars, 2021, Copper Pipe, 3 glass balls, various fabric, rubber, wood, electric cable, and 3 LED lamps, 215 x 220 x 40 cm (c) Courtesy of the artist & PKM Gallery

You learned embroidery and weaving techniques from daily interactions at Seoul local markets, and perhaps these same techniques are also related to your investigation on the female working class in Korea. Could you tell us more about this research?

I was very lucky to have an opportunity to work with a sewer in Old Delhi just after I finished my MA. It was a first collaboration opportunity with a sewer to produce embroidery drawings. Afterwards, I met with female sewers in Dongdaemun market district in Korea to co-produce my project. I learned a lot of useful skills including how to fix my sewing machine during this period. Those skills were learned in person by sewing women who spent their entire adult lives as sewers, that means a lot to me now.

Machine sewing used to be a job for country women who came to Seoul to earn money to support their family. It was a skill they could immediately get a job without specific training or a certificate and it only paid minimum wages to survive. I appreciate that I happened to learn and can sustain this skill as part of my practice that carries the history of undermining women’s labour in modern Korea. Dongdaemun used to be where these sewers were working since early modernisation. This market district is still the most inspiring place for me to go whenever I visit Korea. I get inspired by the busy market districts where garment accessories are ceaselessly designed and produced.

How does this relate to the artwork presented at PKM Gallery?

A Colourful Waterfall and The Stars and Woven and Echoed, they were made based on remarks by former textile female workers who fought for gender equality and fair pay in the 1960s -1970s. I researched and collected their stories for one of my performances called Un-Splitting in 2019. These textile works are re-worked outcomes of Un-Splitting through different mediums. Here quoted words and sentences have been turned upside-down and fragmented in order to re-structure large-scale tapestry and textile collage. For me this process was almost like re-writing their individual narratives in order to liberate them from a patriarchal history that hardly gave attention to their voices for a very long time.

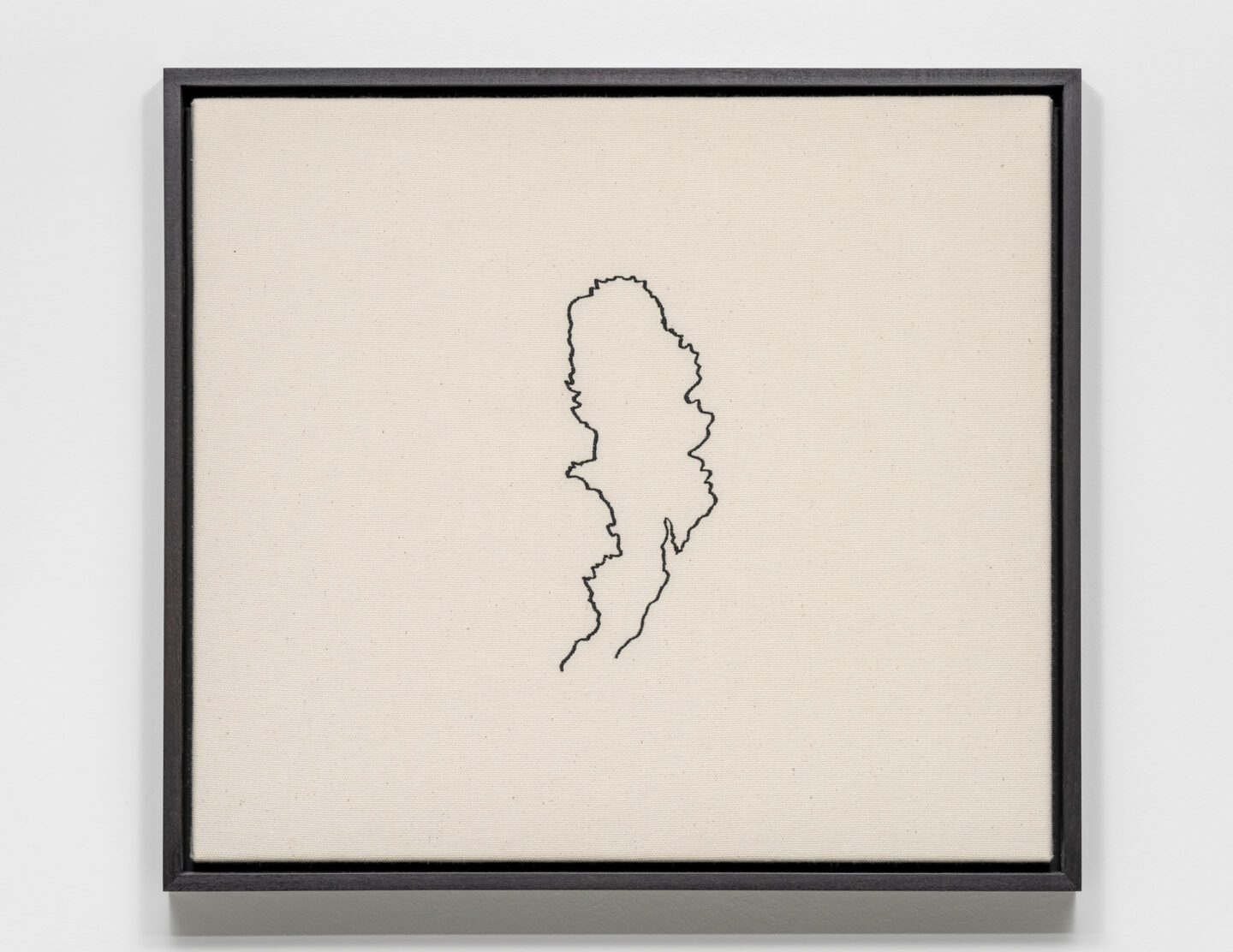

Young In Hong, One Gate between Two Worlds, 2021, Dyed cotton, leather, viscose rayon threads, and rug canvas (on the back), 322 x 297 cm (c) Courtesy of the artist & PKM Gallery.

One of the leitmotifs of your work is the concept of equality. Could you tell us more about your understanding of equality?

I am interested in the notion of equality and in testing how equality is practised, as well as how it can be questioned through art making. For me, equality is not about a = b, but rather more about recognising the space between a and b, which allows us to further explore the relation between the two. In this way, thinking of the animal is, to me, thinking of equality in terms of the space between human and animal, a space that opens up the opportunity to ‘become the other’.

Your artwork “One gate between two worlds” is particularly impressive. It uses references to shrine iconography to discuss the change in our relationship with our ancestors between the pre-modern and contemporary era, but also questions the human gaze towards animals. Could you tell us more about this piece?

There was an underlying theme threading through the exhibition, which is about the coexistence of the spiritual world – the imperceptible – and the real world -the material. In One Gate between Two Worlds this has been represented specifically through this shrine iconography that functioned as a gate between the spiritual and the secular worlds. I wanted to humorously translate it into the heavenly space where gorillas and monkeys are resting as if they are our ancestors. The images of these animals were filmed in Bristol Zoo where they were captivated and observed by humans. I tried to reverse the hierarchical setting by locating them in the sacred space to look down at us as our gazes meet.

In pre-modern Korea, people believed that our ancestors’ souls were always with us. There have been various rituals revealing this folkloric belief system as the shrine pictures show. These rituals have been oppressed throughout the nation’s modernisation because they contradicted the image of industrialised modern Korea. The work and its theatrical image are intended to remind us that some of those rituals disappeared.

“I guess, my interest in ‘the conditions of women in Korea’ isn’t strictly limited to a nation-specific narrative, but is more to do with seeking for ‘other’ sides of self/us, a kind of force that has not been fully understood, thus containing a potential for exploration.”

Your work deals with historical subjects and you often work with concepts linked to modern and postmodern eras focusing on individual and collective history. The postmodern turn allows us to go beyond the idea of understanding history as a unified block, and we increasingly look at alternative histories: to re-write, be critical and see other possibilities beyond established ones. How do you approach these themes in your work, especially in your performance pieces?

I am interested in history. I intend to make each of my work to be a kind of ritual– whether performance or textile work – that re-actualises forgotten historical spaces and times on my own terms. I began producing performances in 2012, which was relatively later in my career yet I was lucky enough to introduce my performances in key international venues thereafter.

When I participated in Gwangju Biennale in 2014, I proposed a performance called 5100: Pentagon, and was given an opportunity to access photo archives documenting the Gwangju uprising in 1980. This made me think about a time and space in the past not fully explored due to strict media control. It was interesting for me that we now have a collective memory based on very limited accessible images.

5100: Pentagon was a piece produced based on the structure of a flashmob. Anyone without restrictions of age, gender and art experience could apply and join based on information distributed online. As long as there was one participant, the performance would go on. The performance included a series of movements choreographed based on the image of bodies of victims or dictators found in the photos, so when teens and elderly people came and performed through their own bodies, the history was re-written differently each time by different individuals.

It was a very emotional experience for the participants as well as the viewers. Because it was based on Gwangju residents’ own history, not only were there participants who had experienced the uprising themselves, young people were also passionate.

Voluntary participation, affective memory and collective agreement altogether allowed the performance to become an actualisation of new history. In this way, when producing performances, I aim to question the authority of art, artists and the boundary of the artwork itself. When the work is in the hands of a random general public, there is always the risk of failing when no one turns up for instance.

“When producing performances, I aim to question the authority of art, artists and the boundary of the artwork itself.”

In your work there are several references to the conditions of women in Korea, how do you envision this discourse today?

Gender inequality is normalised in every corner of society. We now have more terminologies to express and various platforms to share this with others. Yet, in East Asia as well as in the third world countries, where society has long been restrictive, gender hierarchy tends to be firmer although it’s appearing forms and degrees may vary in recent times. Questioning those worn out legacies is one of the roles of the artist, I think.

However, male vs female discourse doesn’t seem productive any longer, seeing beyond the bisectional division of gender and acknowledging marginalised communities in society seem more urgent.

In my recent work, animals and women tend to appear together as in the main gallery, PKM or they become intertwined as in the Un-Splitting (2019) performance. I guess, my interest in ‘the conditions of women in Korea’ isn’t strictly limited to a nation-specific narrative, but is more to do with seeking for ‘other’ sides of self/us, a kind of force that has not been fully understood, thus containing a potential for exploration.

Do you consider your art political?

To me, art being political doesn’t necessarily mean making art in direct response to the current socio-political issues, rather it’s more about questioning the existing orders we are living within. In this sense, good works of art are political, I believe. Political art will allow us to experience perceptual shifts or challenges, which is different to a mere delivery of concept or a set of ideas. In this sense I continuously pursue my work towards its political role.