Quiet as It’s Kept: 10 (Not So Quiet) Women at the Whitney Biennial 2022

The Whitney Biennial has officially opened, presenting a very diverse selection of 63 artists and collectives that span across various mediums, generations, and geographic provenance.

Widely considered one of the most important surveys defining the American contemporary art scene as we know, the Whitney Biennial often also shapes the art market for its participating artists.

Rather than embracing big stands or an unified theme, this year’s edition aims to reflect the precarity of our moment and to complicate what ‘American’ means, and highlighting a long overdue attention for other narratives of the Americas, such as the ones of indigenous communities, Chicanos and Asian American people.

We toured the preview and identified 10 women artists who you should definitely keep an eye on!

RENÉE GREEN (Cleveland, 1959)

Right at the entrance of the Whitney Biennial you’ll find Green’colorful banners “Lessons” ( 1989) which present a series of poetic reflections on museums and their collections—it includes a collection within itself.

Known for her densely layered, multifaceted artworks, these Space Poems – as Green calls them- are experiments in associative thinking fused with the artist’s interest in printmaking, design, typography, and architecture. They have already also appeared in other intersectional spaces as lobbies and corridors of other museums, such as most recently the ICA Boston (that also acquired them), the Walker Art Center, MoMa Media Lounge, among the others . The artist is represented by Bortolami in New York, and Galerie Nagel and Daxler, Berlin.

LUCY RAVEN (Tucson, 1977)

Lucy Raven explores the system of power and distribution of resources through complex multimedia installations and hypnotic video narrations.

In this Whitney Biennial her video Demolition of the Wall (Album II) (2022) invades the dedicated room and expands in all the Whitney Biennial exhibition space with the echo of an explosion she recorded in a region of New Mexico used for tests by the US Department of Defence and energy. Part of her trilogy “Westerns”, the work reflects the US military power aspirations, and its implications in the world’s politics, staging the contrasts between the “Western” as part of a long expansionist myth long celebrated in the Americana movies, and this “Western” territories of military tests.

Despite never having had any gallery before, an announcement just a few days before the opening revealed that she will directly jump to the roster of a powerhouse as Lisson Gallery. Raven had previously drawn widespread acclaim for her memorable film Ready Mix(2021), presented last year at the Dia Art Foundation in New York. Later this year, she will premiere a new film installation at the WIELS Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels.

LISA ALVARADO (San Antonio, 1982)

Rooted in her San Antonio Childhood, Lisa Alvarado’s bright and dizzying colorful works are deeply animated by the lights of the South, feeling “at once spiritual and grounded in the physical, natural world,” as she has described.

Partially inspired by Mayan textiles and in strong connection with her identity as Chicana, her often double-sided canvases are built of gestural strokes creating electric patterns that eventually evokes natural texture from the dessert.

For the Whitney Biennial she’s presenting a new series of these suspended abstract paintings map, that, as Alvarado has written, are a form of navigation that is attuned to the body’s pulsations and breaths.

Alvarado is rapidly emerging as one of the brightest rising American Chicana artists, having already been presented at Frieze Art Fair, Glasgow’s Modern Institute, Ballroom Marfa, among the others. Curious fact: her art is not only painting as she’s a prodigious harmonium player as well, after falling in love for music and jazz in Windy City’s bustling music scene.

EMILY BARKER (San Diego, 1992)

Emily Barker is an artist and activist based in Los Angeles whose practice interestingly intersects the institutional critique, to address in particular the accessibility of spaces, and how these often erase disabled bodies. Being affected to a chronic illness, Barker practices a language about marginalization and hidden obstacles that they encounters on her way everyday as disabled person. At the Whitney they’re presenting Kitchen (2019), an imposing transparent structure they built based on their own experiences using a wheelchair and exaggerating the height of the countertops—which, at five feet and nine inches, are the average height of adult men in the United States – aiming to show how “the seemingly mundane built environment and the mass production of objects harms people every day.” In Death by 7,865 Papercuts , they highlights the inaccessibility of healthcare and insurance systems by assembling photocopied medical bills and documents from 3 years of their life into columns of papers that may recall the minimal forms of artists such as Donald Judd or Felix Gonzalez-Torres, as “sheer volume of bureaucracy with which one has to deal after a spinal-cord injury and with chronic illness.”

REBECCA BELMORE (Upsala, Canada, 1960)

Rebecca Belmore is an Anishinaabekwe primarily performance artist whose socially aware works are centred around politics of representation and identity, focusing in particular on violence and injustice against First Nations people, and especially women.

In this Whitney Biennial she’s presenting this sleeping bag that suggests the contour of a human body, despite being totally empty inside, and surrounded by thousands of empty bullet casings which work both as its protection and threat. The sculpture titled ishkode (fire), 2021 alludes to the centrality and precarity of the earth itself, within the relational regime the mankind is establishing nowadays with it.

In addition to her Canada Pavilion at the Venice Biennial in 2005, Rebecca has presented in multiple institutional moments including documenta 14 (2017), 3rd Tirana Biennale, and the IV Bienal de la Habana, in 1991. With the rise of indigenous practices in contemporary art and this Whitney participation with such a poignant work, we can expect her practice to get back to some great institutional (and probably also market) attention soon.

THERESA HAK KYUNG CHA (Busan, 1951)

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha is definitely one of those figures long overlooked, that with those flagship events finally get their long deserved recognition. The avant-garde artist, novelist, producer, director, is best known for her 1982 novel, Dictee, where she explored minority identity in an experimental and radical style, but which is also largely considered also to have cost her life, being murdered in New York by a security guard few months later.

Organized in collaboration with the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) this group of artist books, films, documentations of performance is a tribute to this pioneer artist within this year Biennial, and the first presentation after more than thirty years after the Withney dedicated her a solo exhibition in 1993.

Her art practice was very radical but also very poetic, creating a thrilling body of conceptual and performative art that explored notions of displacement, linguistic misunderstanding, rejection and immigrant life that, as her razor sharp novels, provided a key contribution in the reckoning of Asian American identities and literature.

NA MIRA (Lawrence, KS, 1982)

The work of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha is a favored subject of Na Mira, who is presenting on the Whitney 6° Floor Night Vision (Red as never been), 2022, a touching but also hypnotic video that commemorates her death. Adopting a disorienting aesthetic of glitches and infrared, the artist erase any sense of place and time, driving the viewer in nightmare-like dimension. The installation includes the sound of a Korean radio station that is transmitted by an unknown source in the artist’s studio as well as audio from Mira’s recreation of a performances at the site of artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s 1982 murder and the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea.

Mira has explained: “scenes from the past repeat as the footage continues to move in the present . . . what is past continues to be held with us.”

Past and present memories and factual elements interact in an open-ended back and forth as the artist embodies the experience of the trauma, guiding the viewer into the historical subconscious.

ARIA DEAN (Los Angeles, 1993)

Aria Dean is known first as curator and editor of the platform Rhizome, but she’s also rapidly emerging as visual artist, especially after having been recently included in the Hammer Museum’s biennial Made in L.A. 2020 and having already presented her work at REDCAT, Los Angeles (2021); Greene Naftali, New York (2021); Chateau Shatto, Los Angeles; Artists Space, New York (2020); Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, Geneva (2019); and the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York (2018), among the others.

Challenging boundering between abstraction and figuration, her multi-platform body of work is centered around trenchant critiques of representational systems.

Often adopting an extremely minimal language, she addresses issues of race, power, through no better identified forms that she first digital designed and then translated into industrial materials. At the Whitney Biennial she’s presenting Little Island/Gut Punch (2022), a green chromakey monolythe: fabricated in the same color of greenscreen it playfully interact and challenge the idea of anti-illusionists targeted by 1960s minimalist sculptures, as pretext to address the possible lack of links between forms, reality and the concepts behind, more in general in our daily experience of the world and in ideologies that media society can propose.

COCO FUSCO (New York, 1960)

For years Fusco has been an icon of the fight for the recognition of Latino/Latinx community within the American Society, which resulted in being eventually awarded last year’s 2021 Latinx Artists Fellowship.

As Cuban-American, her work often drew from the history of the relations between these two countries, as well as more broad themes of race, discriminations and all the colonial bias embedded in American popular culture.

After her most recent memorable speech against economic violence impersonating the chimpanzee-dressed psychologist Dr.Zica from Planet of the Apes, and the historically important and shocking Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West, she and Guillermo Gómez-Peña performed at the Whitney Biennial in 1993, she’s now back with another highly provocative but much more sentimental video: Your Eyes Will be an Empty World, (2021) features footage of the artists going errand by boat around Hart Island, which since 1869 was first used as prison labor to bury more than a million people in mass graves also after the civil wars and especially with the pandemics. Later, it was turned into the city of New York Public cemetery operated by the city’ department of correction over all the pandemic.

Starting from a critical reflection on these historical parallels the artist draws a series of reflections on the sense of death, its perception, and how this has changed and sometimes manipulated over time, and in particular over the pandemic. Presented as an hypnotic artist voice-over on contastically poetic aerial views of the island’s bright nature, this work setss somehow a change of tone for the artist, for an intimate but extremely poignant work on universal messages.

The artist will be also part of the upcoming Venice Biennale, and she’s represented by Alexander Gray Associates.

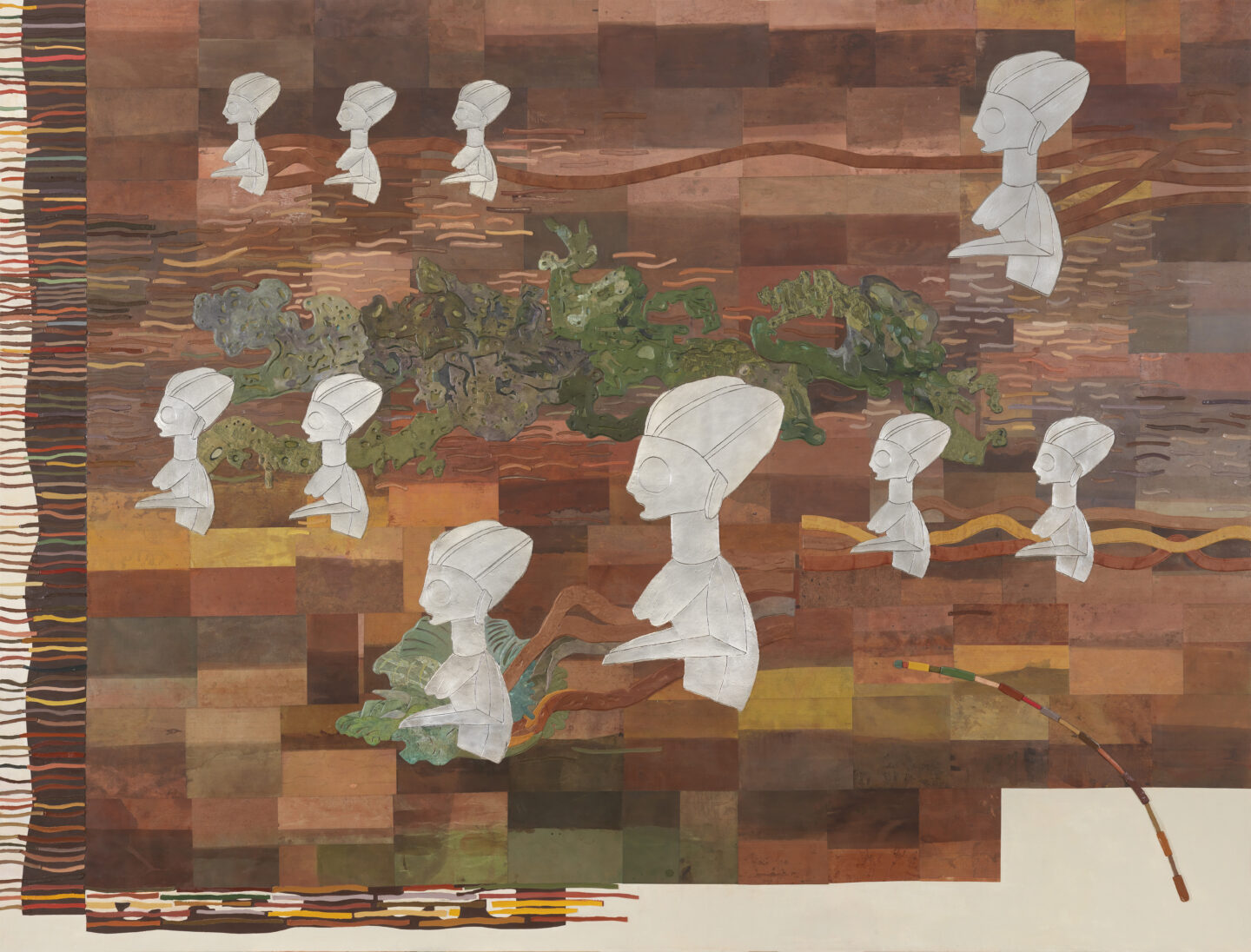

ELLEN GALLENGHER (Providence, 1965)

Ellen Gallengher works on a kind of contemporary archeology of African American culture, as a form of resistance and identitarian revindication.

In her (Ecstatic Draught of Fishes (2022), presented in this Biennial, she creates a multi-part work featuring apparently paradoxical entanglements and connections between matter and history. These works may suggest a cultural fragmentation, but at the same time they also invoke to the need to imagine some possible constellations of meaning, so that cultural memories can start to be reconstructed starting also from minimal symbols that survived the erauseìure of the official history.

Gallagher has written: “The precious material of culture that, far from being left behind, sank to the bottom of the sea, suddenly resurfaced as a fossilized network. Irretrievable loss made insurgent memory. As if to say that culture is never only physical, nor only in the mind. In the face of relentless destructive attacks on a culture, a steady beat of anti-Blackness, what survives?”

Among the already very established artists the Whitney Biennial is paying tribute to, Gallengher is already prominent museum collections in the country as the MoMa, New York; Albright Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Art Institute of Chicago; MCA Chicago; MOCA, Los Angeles; Philadelphia Museum of Art, New York; Whitney Museum of Art, New York; Tate, London; and Centre Pompidou, Paris. She’s represented by juggernaut gallery Hauser Wirth, which dedicated her a show last year in London.

The 2022 Biennial takes over most of the Whitney from April 6 through September 5, with portions of the exhibition and some programs continuing through October 23, 2022.

This year’s edition is co-organized by David Breslin, DeMartini Family Curator and Director of Curatorial Initiatives, and Adrienne Edwards, Engell Speyer Family Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs, with Gabriel Almeida Baroja, Curatorial Project Assistant, and Margaret Kross, former Senior Curatorial Assistant.