Hangama Amiri: A Thread Between Yale and Afghanistan

Afghan-Canadian artist Hangama Amiri left Afghanistan when she was only six, embarking in an adventurous journey as refugee which brought her first to Pakistan and later Tajikistan, before being resettled in Canada in 2005.

Fast forward to the present, she recently graduated from the prestigious Yale MFA program in the Painting and Printmaking Department attracting the attention of the international art world: just last month Toronto-leading gallery Cooper Cole announced her representation, and this December her solo presentation at NADA Miami by Towards Gallery was awarded an inaugural MobileCoin Art Prize.

Still, her home country still is much present in her work, which pursues a reinterpretation of traditional Afghan textile and embroidered fabrics, aiming to celebrate the achievements of contemporary Afghan women, at least before the Taliban’s take-over last month.

We talked with her about these connection with her home country and its culture, in occasion of Qatra Qatra/Drop by Drop – Perspectives from Afghanistan at Fondazione Imago Mundi, Treviso (until Jan 9th) a group show aiming to keep under the spotlight the situation of Afghanistan, while exploring its contemporary art scene through the work of 4 courageous Afghan women.

Despite leaving Afghanistan at the age of six, your native country and its culture are still much present in your works. In your practice you draw directly from Afghan costumes, and the Islamic culture. In particular, with the reinterpretation of traditional Afghan textile and embroidered fabrics, with your works you aim to celebrate the contemporary lifestyle of Afghan women. Can you tell us more about this practice and how this purposely embraces and reinvents the culture of your native country?

Growing up abroad far from Afghanistan, I constantly had a desire to re-experience those childhood memories of shopping with my cousins in the bazaar or going to the tailor shop with my aunts to sew their own more modern style clothing. These are the kinds of memories that continue to motivate me to learn more about the culture I departed from at such a young age without me choosing it.

As an artist today, however, I have the privilege to reinterpret those stories while also simultaneously looking at the contemporary daily lifestyles of Afghan women. During my visits back to Kabul, for example, I witnessed fashionably dressed modern Afghan women working in the malls, in beauty parlors, sipping coffee in cafes, and on tv screens as singers, journalists, and hosts for a range of entertainment programs. Witnessing both the powerful and fragile changes around their mobility and public visibility was such a strong contrast compared to how my own mom and five aunts lived experiences were back in the early 90’s. The existence of a hybrid contemporary Afghan culture, that embraced both traditional garments and more modern clothing, is what ultimately influenced me to use a range of fabrics within my own work. I therefore use traditional Afghan embroidered fabrics—like those worn by women during their wedding ceremonies—alongside more modern fabrics such as denim and polyester, which I am especially fond of because of its shimmering surface.

Unfortunately, as I, and many others have witnessed, the power of Talban regime has once again taken hold of Afghanistan and women’s visibility in public spaces is in question. Women in Afghanistan are now more than ever rightly worried about their future, identity, and autonomy in their society. I will continue to reference these women’s taste in fashion, self-empowerment, beautification, and economic power in my work as a way to honor how Afghan women always look more towards progressive change amidst the instability and change around them.

Mariam Beauty Salon and Journalist, the two works you’re presenting in Qatra Qatra are both also part of this ongoing exploration into the traditional Afghan textile art, while questioning standards of beauty and the rights of women across different levels of Afghan society. Both works, in fact, challenge this traditionalism and its social norms that only serve to maintain the status-quo of a patriarchal and male-dominated society. Can you tell us a little bit about the stories of the women woven in these embroideries?

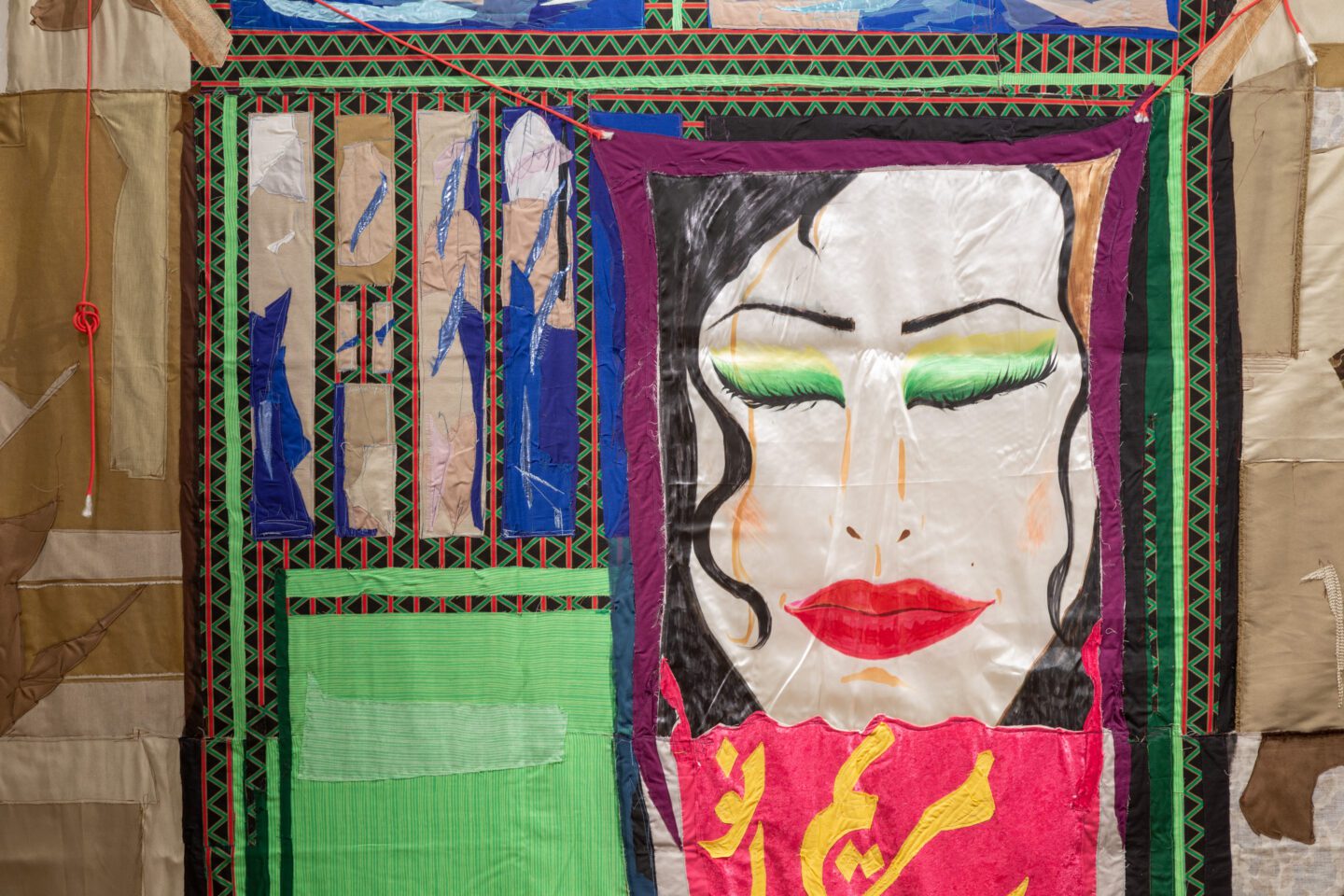

The first piece, Mariam Beauty Salon, was a part of my 2020 solo exhibition Bazaar: A Recollection of Home at T293 gallery in Rome. In this series, I focused on the entrepreneurial and leadership roles of women across a range of traditionally male dominated communities and businesses. This piece, among other works in the exhibition, engages conversation around the representation of Afghan businesswomen and the spaces they own and have named after themselves. It highlights their progress, identity, and participation in the economy over the two decades after the fall of the Taliban when beauty parlors flourished. The aim of the project was ultimately to celebrate women’s representation and their presence in the workplace within Afghanistan’s urbanized society.

The second piece, Journalist, is dedicated to Afghan women journalists from the past and present. After the Taliban regime took over control of the country in August of this year, we have seen devastating news of the harming of journalists in the city who are participating in the media and exposing local injustices. In this piece, I framed the portrait with a black border to suggest that it is a tv screen. The female journalist is shown reporting boldly while standing and gazing out at the viewer. In the background, we see the cityscape of Kabul. This piece was meant to portray my women’s character as someone who is fearlessly taking a stand against injustices as opposed to being a passive victim.

Your work has often addressed your condition as a refugee. We know you have been creating the emojis for World Refugee Day this summer promoted by UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency. Can you tell us a little bit about this project? Actually, it was a UNHCR art program offered to refugee children that had a decisive role in creating the basis of your life as an artist, wasn’t it?

Working on this project with UNHCR was meaningful to me because they were one of the two important organizations that helped my family and I immigrate to Canada in 2005. UNHCR played such an important role in my own transition to Canada and introduction to art that, when they asked me to participate in designing the emoji for world refugee day, I could not help but say yes. It meant a lot to me as a refugee to participate in the design of such an important symbol which would then be shared globally in order to bring awareness to the hardships faced by those currently being displaced around the world. My own design ended up having two hands cupping a heart symbol in between then to reflect ideas of togetherness, wholeness, belonging, and love.

Afghan-native artists working internationally may help to open up a different point of view on Afghan traditions and hopefully escape a sometimes restrictive regional identification. Have your works be shown in the international art world circuit, and how do you feel it is perceived? Do people still identify you as an Afghan artist?

Since Canada is my second home, I have been identified both as an Afghan artist and an Afghan Canadian artist. I feel like I have always been interested in ideas of in-betweenness, something that is neither from here nor from there. This echoes my own experiences of having lived in Afghanistan for a short time before moving around and eventually settling in Canada. As an artist, however, I am interested in being connected to and aware of the constant political changes in society. I therefore use art to bridge connections between the Afghan diaspora by referencing experiences centered around the home and migration, but also current events happening in Afghanistan like women’s access to education and their participation in society under the Taliban. It is a sad reality to watch from a far, but it is my responsibility as an artist to bring conversations into focus regardless of whether it is in a gallery or art fair. I take it as another form of education, bringing awareness, expanding our views, and learning from each other.

Let’s get to more casual questions – dream tea catch up (as in Afghanistan, tea is a big conversation moment): with which artist, and where?

I would love to have a tea with Kerry James Marshall at any art museum that displays historical painting along his own work so that we could talk about art of the past and the present. That would be a dream come true!

Name 3 women artists who you admire and are an inspiration for you.

For me,the three most influential women artists today are: Deana Lawson, Rina Banerjee, and Wangechi Mutu

Looking ahead, what’s next for you? I know you had some work at NADA during Miami Art week, but what’s on your schedule for this 2022?

I have two upcoming solo shows for next year. The first will take place at David B. Smith Gallery in Denver, Colorado and the second will be at Union Pacific gallery in London, UK. I am looking forward to seeing how my work will respond and develop in these two different contexts.