Dorothea Tanning: Surrealism and Gothic Nightmares

Last of the post-war surrealists, Dorothea Tanning’s uncanny paintings and unnerving sculptures are still pushing the boundaries in galleries around the world.

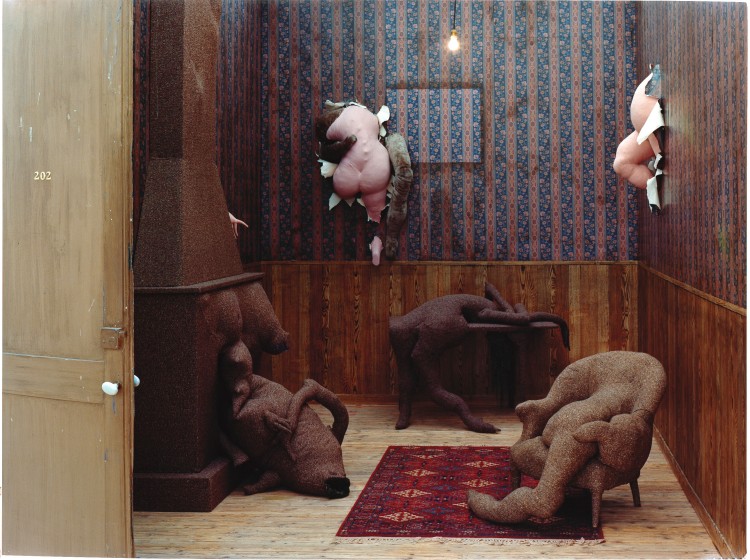

Have you ever entered a hotel room and something seemed unsettling? Nothing immediate, nor visibly wrong, just an air of unease. Then you notice it – a leg is protruding from the fireplace and a contorted arm is growing from an armchair. Figures are appearing around you, not quite alien, but not quite human, an uncanny balance. They seem to be pulsating and bones are protruding, yet they are made from cushioned pillows. Seeing this, one might question if they are within a dream or a Hieronymous Bosch-esque nightmare. So is the feeling evoked from walking into Dorothea Tanning’s 1970 installation Chambre 202, Hôtel du Pavot. This seedy hotel room has been described by critics as the final masterpiece of surrealism and is evidence of one of the greatest surrealists.

Dorothea Tanning was born in 1910 in the small town of Galesburg, Illinois. From an early age she was encouraged by her parents to attend art school, but quit after a week, stating: “I thought you had to go to art school. It would be a kind of initiation like being baptised — in paint. They took my money, only for me to sit down and draw. I threw down my charcoal and left.” Tanning then moved to Chicago, supporting herself as a commercial painter, before discovering Surrealism in New York.

Tanning’s early paintings immediately displayed her taste for the unsettling moods and fantastic uncertainty of Gothic novels. Her childhood bedroom was known to be lined wall to wall with authors such as Poe, Maupassant, Coleridge and Flaubert, authors who she claimed “forever corrupted my psyche.” She moved to New York in 1940, at a time when the Second World War saw an influx of European cultural migration, an influx that gave a post-war doldrum society a shot in the arm. In New York, Tanning was exposed to the centre of the avant-garde world, visiting the seminal 1936 exhibition, Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism. Inspired, she painted the self portrait Birthday 1942, which attracted the attention of fellow artist Max Ernst, they later married and quickly became the two most prominent exponents of the New York Surrealist movement.

Surrealism opened a path for Tanning to materialise Freudian psychoanalysis, that was rarely explored outside of literary academia. In her memoir, Between Lives, Tanning wrote: “it can safely be said that during this last century, our way of seeing the world was profoundly changed by contact with the surreal.” The founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, was exploring the unconscious mind through the study of dreams. He positioned recurring images found in sleep as the answer to understanding our conscious actions. Tanning adapted Freud through the expression of painting, giving her unconscious the ability to express itself, by creating images that blur the lines between reality and fantasy.

One of her most famous paintings; Eine Kleine Nachtmusik 1943 (A Little Night Music) depicts two children walking through a dreary hallway, approaching an uncannily oversized sunflower. Doll-like, their hair is consciously aware, moving independently to the head. In the hall, three doors remain closed whilst one is ajar, revealing a bright light, a recurring image in Tanning’s works. The door, neither open, nor closed, is a surrealist motif creating a fear and unquenched desire to know desperately what lurks behind, but that reveal is never coming. Retrospectively observers have suggested the unnamed horror behind the door, parallels the images that would later appear in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Others have interpreted the door as the exit from the conscious to the subconscious.

In the 1960s and 70s, Dorothea Tanning moved away from painting unsettling moods, to recreating them within a physical space. Installations of soft sculpture creatures bulging from upholstery that face the viewer were a groundbreaking step for Tanning to take. She described the figures as “living materials becoming living sculptures, their life span something like ours.” Using fabrics lined with stuffing and contorted with sewing pins, the figures are as beautiful as they are grotesque. They stand and sit alongside the viewer and, with one pacing glance, appear to be pulsating. One of Tanning’s earlier examples was Rainy Day Canapé 1970, ‘in which’, as one critic described, ‘a body appears to be struggling to birth itself from inside the upholstery of a couch’. Nue Couchée 1970 (translated as ‘reclining nude’) is a surrealist challenge on the patriarchal view of the female sitter of classical works. Rather than the passive female euphorically laying for a painter, Tanning’s figure is tormented, struggling to untwist itself. The exposed back is connected to spindly limbs that lock and knot, suggesting the self conscious torment of the female sitter made visible.

Throughout her 80-year-career, what Tanning felt most aggrieved about was being placed within a category. ‘Artist’s wife’, ‘surrealist’, ‘woman artist’ – she opposed the classifying language used by critics, that no matter how well-intended, attempted to define her. In an interview, Tanning responded to a description that brought up her gender, claiming: “there is no such thing [as a woman artist] – or person. It’s just as much a contradiction in terms as ‘man artist’ or ‘elephant artist’.”

Dorothea Tanning is criminally unknown for how much her work has inspired later artists; Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining and David Lynch’s Twin Peaks and Eraserhead all owe a great deal of their imagery to Tanning. Artists such as Louise Bourgeois and Sarah Lucas hold Tanning as a key influence, especially her sculptural pieces. Photographers such as Sally Mann draw from Tanning’s eroticism, when depicting the human form, from adolescence to adulthood.

By the time she was In her eighties, Dorothea Tanning had reworked her surrealist outlook and turned increasingly to language, writing two anthologies of poetry. She died in 2012, at the age of 101.

Despite the end of her London solo show, Tanning’s sculptures and installations can still be found at the Tate Modern. She also is currently on view in New York, at the Gallery of Heather James Fine Art’s new exhibition The Female Gaze: Women surrealists in the Americas and Europe. The exhibition is showing female surrealists from Leonora Carrington to Dorothea Tanning, available to the 31st July.

Featured Image: Dorothea Tanning, ‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik,’ 1940.