With Every Instagram Post, Katy Hessel of ‘The Great Women Artists’ is Rewriting Art History

The founder of cult-instagram account ‘The Great Women Artists’ talks about idealised beauty, women’s art at auction and creating systemic change for women in art.

ONE FRIDAY NIGHT in 2018, the hammer fell at Sotheby’s auction house, New Bond Street. Jenny Saville had just become the world’s most expensive living female artist, her 1992 work ‘Propped’ selling for $12.4 million.

It’s a monumental sum, but compared to her male counterpart David Hockney, Saville’s record at auction accounts for just 10% of Hockney’s 1972 ‘Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)’ which sold a month later for $90.3 million.

This financial chasm between male and women artists comes as no surprise. As the value of an artwork is boosted by its provenance (artist and work history) and the artist’s exhibition history, far greater industry recognition is needed if female artists are to equal their male peers in auction houses.

Women are slowly gaining footholds however. In May 2018, the work of Nigerian-born American artist Toyin Ojih Odutola sold for $62.5k – close to five times its estimate and the same went for Jordan Casteel’s work, which at a selling price of $81.24k, was nearly four times its estimate. These sales are impressive, considering the age of Ojih Odutola (34) and Casteel (30) and that it was the first time at auction for both these artists.

“Our duty as art historians or art lovers is to pay our attention to these female artists and understand their greatness. They need to be placed on a pedestal and lifted to the same height as their male counterparts.” —Katy Hessel, The Great Women Artists

If we are to buck the trend which sees art by women artists valued less than that of male artists, female artists need more exhibitions, higher representation in galleries and by consequence, higher public awareness of their work. At Art Basel 2019, just a 1/3 of the exhibitions (both public and commercial) were by women and a comparison of the 3,050 galleries on Artsy’s database shows while 48% represent female artists, women account for no more than a quarter of the artists in these galleries.

Only in February, London-based artist and art consultant Tai Shani tweeted about her continual struggle to make ends meet, despite having major UK shows and tutoring at the Royal College of Art. When displayed in black and white figures, the maths of the art world communicates the difficult reality that female artists are facing.

I picked up these art market insights from Katy Hessel’s ‘Women at Auction’ talk, delivered at Christie’s auction house in London. Katy – an authority on women’s art – was galvanized into action while at a major art fair, shocked to discover that no female artists were exhibiting. Determined to inscribe women into the annals of art history, she launched ‘The Great Women Artists’ instagram account, seeking to disrupt the norm in which female artists have been overlooked or forgotten.

Since she founded the account four years ago, Katy has amassed a cult-following of 53k+. She shines a light on exceptional female artists from around the globe, sharing a mix of new talent and old masters along with a short, insightful explainer text. What’s invaluable is the platform that Katy’s instagram provides, both for the artists she showcases and for our wider education about female artists.

Nothing short of an inspiration, Katy is down to earth and unboundedly passionate about female artists gaining the recognition they deserve. I met Katy for cup of tea on a typically drizzly London day, to chat about social media, the women artists that inspire her and how we can create systemic change for female artists.

'The Great Women Artists' is now a hugely influential instagram account. Why is social media an invaluable tool, particularly for female artists?

Instagram is much more reflective of art history than galleries currently are. There are so many female artists on Instagram; finally we have a platform that is truly reflective of what art (and the world) really is. There is an enormous diversity of female artists on Instagram too, from classically trained painters and videographers to artists such as Unskilled Worker. She’s a London-based self-taught artist who started practicing when she was 48, now she collaborates with Gucci!

Instagram is also a great introduction to art, which at times can be so elitist and inaccessible. The internet strips off that stuffiness and opens the conversation up, making art is digestible. There is still the same thought and depth of expression, but without all the highbrow theories. Instagram makes art democratic. It’s easy to find art that personally resonates with you. There’s a whole host of artists that young people can connect to, because they are creating art based on social phenomena or political developments. Alice Skinner is an activist artist and illustrator. She might draw in response to yesterday’s political event and then publish on instagram. You wouldn’t necessarily get that immediacy inside a gallery. Instagram is a platform for all different ages to take you seriously and the entire art world is on it. We’ve got to grab onto it and utilize the online space.

You attended Sotheby's Masters' Week spotlight on 'The Female Triumphant' in January. Why was this a turning point for women artists in many ways?

It was a first in so many ways. Never before have the works of so many female Masters been together in one room. It was powerful. Victoria Beckham partnered with the auction house for this celebration of female Masters and her influence helped reach young, contemporary audiences. Showing old works to new audiences means people can engage with this section of art history that they were unaware of.

All the female masters were connected through incredible stories of resilience. Women in the 15th Century were banned from apprenticeships, so they had to fight hard to become an artist. They were pioneering for their time and have not been given the platform they deserve in recent years. Belgian painter Clara Peeters wove a self-portrait into her work, decades before Velazquez. While Dutch still-life artist Rachel Ruysch was paintings, her commissions were worth more than the price of a Rembrandt who worked around a similar time. Catharina van Hemessen was a Flemish Renaissance painter who replaced Hans Holbein as King Henry VIII’s court painter of VIII. She was paid a considerably higher salary.

Some – not all – of these women were really successful during their own lifetime. The reason we are largely unfamiliar with them is because of the way art history and education has been written, with some women left out.

You curated an exhibition called ‘In the Company Of’ where you presented female artists of the 20th century alongside newer women artists. Why did you choose to blend old with new?

I see Barbara Hepworth, Lee Miller and Alice Neel as the female Greats of the 20th century. They were remarkable women but so many don’t know who they are. People just think of Lee Miller as a fashion model turned Man Ray’s lover and muse. But she was also a war photographer and an incredible Surrealist who shot brutally honest photos on the frontline. Her story is fascinating. Suffering from PTSD after the war, Miller locked away all her photographs. Even her own children didn’t realise the extent of who she was because she never spoke about her photography. Thanks to Miller’s daughter and granddaughter, her work has now been reinserted into art history. Miller was truly fearless. She took a photo naked in Hitler’s bath!

Alice Neel was an impressive portrait painter who broke every boundary in portraiture. She painted at the same time as the Abstract Expressionists in New York yet remained unshakeable, staying loyal to her own subject and style.

I wanted to introduce these women to people and then understand how they are relevant to the present day as well. Artists are constantly referencing the themes in these works, perhaps stylistically or subjectively so the exhibition was a celebration of women artists past and present – also what my Instagram does.

Women have so frequently been the object in art history but as in Lee Miller’s case, they were also artists in their own right. It is too easy to place women in the ‘beautiful’ category without understanding their true worth, that’s how society has been programmed to look at women.

How far have we come since the Guerrilla Girls and ‘do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?’

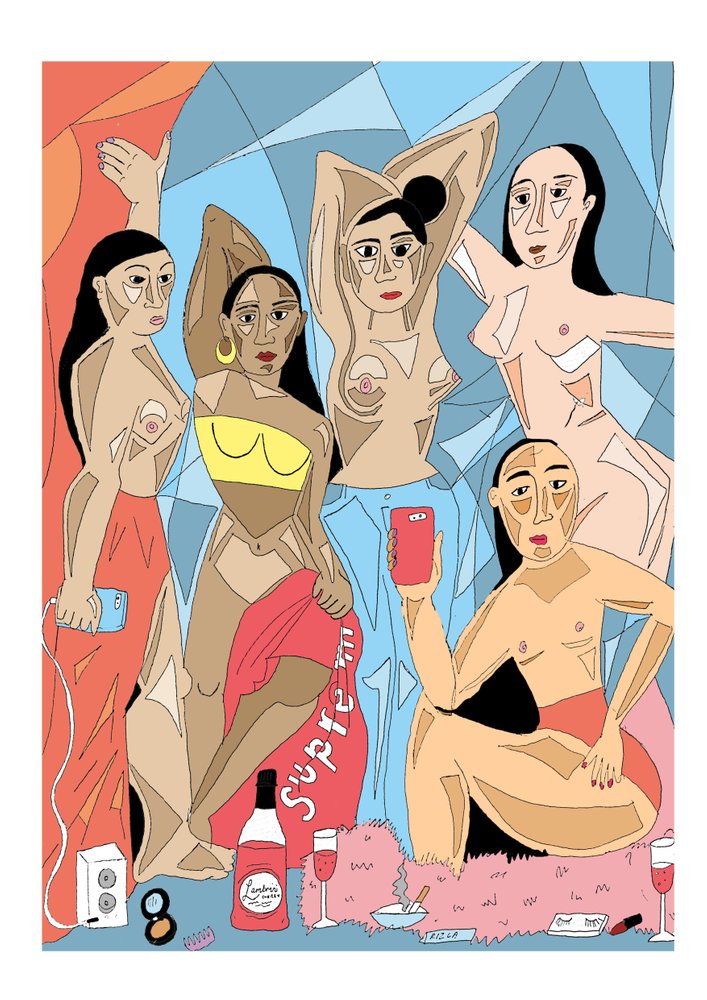

Nowadays I don’t know many women artists who paint naked women. German artist Paula Modersohn-Becker painted such emotional self-portraits and Alice Neel’s portraits are the exact opposite of idealized beauty. Her portraits get into the psyche of what is means to be a woman. So often in art, we see women as objectified beings. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres painted idealized female nudes and it set impossible standards for women to aspire to. Contrast Ingres’ The Source (1820-1856) with Alice Neel’s portraits of women naked; the difference is huge. Neel’s bulbous pregnant women are both beautiful and abject, a true representation of pregnancy that portrays the reality of being a woman. The body can allude to so many different things, the landscape, psychology, perception and more. Neel even fearlessly painted men naked, which was at times emasculating for them but it was her honest image of them.

The idealized female beauty we see in so many art galleries stems from the way artists were taught to draw a female torso. All they had to go off was the female classical body, a white perfect marble form. The modern day equivalent of that might be Barbie – completely unattainable and not a realistic depiction of women.

Why have there traditionally been less female artists?

Women weren’t given the same opportunities as their male counterparts. They were banned from apprenticeships, restricted solely to portraiture and only permitted to become an artist if their father was one. To paint, women had to overcome greater challenges and the ones who succeeded fought back.

Also many artworks painted by women were in fact attributed to men. Most of Dutch master Judith Leyster’s oeuvre was assumed to be the work of Frans Hals or her husband Jan Miense Molenaer. It wasn’t until the turn of the century that people realised Leyster was the artist.

The front cover of Linda Nochlin’s 1971 book ‘Why have there been no great women artists’ is a prime example. The portrait of the young woman drawing that decorates the front cover was assumed to be that of French painter Jacques-Louis David but it was actually painted by Marie-Denise Villers. It is thought to be a painting of the artist herself. In the 1920s it was sold to the Metropolitan Museum for $200,000 but if they had known it was the work of a female artist, the painting wouldn’t have sold for that much. There is a status attached to male artists. There have been plenty of female artists, they have just been overlooked.

How can we address the issues of provenance and peer-recognition, essential for generating value for female artists?

People aren’t ignoring art just because it is by a woman, it is because they haven’t heard of them. There are barely any books written about female artists and if you go up to someone on the street, what is the likelihood that they will name a female artist off the top of their head? We need to build female artists into education and celebrate them.

We can create change by giving women artists more opportunities in museums. Having women at the head of museums makes a huge difference. The directors of London’s Tate Modern, Maria Balshaw and Frances Morris are very conscious of collecting an equal number of female and male artists. Right now, the Barbican in London will show Lee Krasner this summer, an American abstract expressionist painter whose art had always been overshadowed by her marriage to Jackson Pollock. Previously Krasner’s work was never at major auctions but because of this recent publicity, the penny is dropping about Krasner’s excellence and her work is appearing at auctions. It’s about giving women artists an institutional platform, because of the prestige and education bound up with this. Of course, museums have to sell tickets, but they should take the risk and exhibit the work of lesser known female artists.

How have the calls for gender parity in society at general and #MeToo impacted the art world?

Art is supposed to represent or reflect the time we are living in, in the same way that so much art now is about technology because we live in a digital era. It’s great that society is addressing issues of gender equality and shocking that it didn’t happen sooner. While we still have so much further to go, if we start now we can make a positive impact.

The Sotheby’s auction in May 2018 spotlighted women artists by giving the first seven lots to women. Much like the spotlight on ‘The Female Triumphant’ in Masters Week, it wasn’t a sale in its own right but the act of highlighting the female artists proved successful – there were seven world records for artists in that sale. It also showed that these works should be aligned in terms of their value with works by their male counterparts. On the other hand, I think that ‘female only’ sales should be avoided because then you risk pigeonholing female artists by their gender. All-female exhibitions are necessary however because it’s the curatorial aspect that has the power to address this overlooked part of the art world. At the end of the day all we want is equality, but we may need to overcompensate right now and fight a little bit harder for that.

How can we make art by female artists appeal to men and make men feel that they have a voice on these issues?

I think women champion other women so much more than men do to one another. I would hate to think that men are hesitant to join in a conversation because this may come less naturally to them. Some of the rhetoric around feminism can alienate men by making generalisations, which is the exact opposite of what needs to happen. It’s a problem within the #MeToo movement, which can polarise men and women. Men need to be on board with equality if there is to be any progress. We can’t be aggressive; the conversation should be for everyone and it should consider the experiences of both genders.

Which women artists do you currently have your eye on?

Kate Dunn is a painter that was classically trained in Florence but now has moved onto completely abstract painting. Although abstract, she still adopts classical forms into her work, creating a painting with the same dimensions as you would find at San Marco’s monastery and her strokes allude to Christ-like forms. She manages to achieve her own identity within abstraction which is hard to do.

I also love Antonia Showering, Caroline Walker, Flora Yukhnovich, Maria Berrio, Simone Doig, Erin Lawlor and Toyin Ojih Odutola, who I think is amazing.