Women Curating Women: Donna Karan and Mashonda Tifrere’s ‘King Woman’ Exhibition

On International Women’s Day, ArtLeadHer opened King Woman, a collaborative curation between Tifrere and Karan at Urban Zen, 705 Greenwich Street, New York City.

THIS WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH, we attended ArtLeadHer’s ‘Women Curating Women’ panel, which featured opening remarks by fashion icon and philanthropist, Donna Karan, and panelists Carmen Hermo (Associate Curator, Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art), Joeonna Bellorado-Samuels (Director, Jack Shainman Gallery), and Ysabel Pinyol (Curatorial Director, Mana Contemporary). The discussion was moderated by ArtLeadHer’s founder, Mashonda Tifrere, whose mission is to empower women in the art world.

Both Karan and Tifrere have a history of using their public platforms to foster cultural initiatives within and beyond the arts. Tifrere, through ArtLeadHer, looks to increase representation of women in the visual arts by presenting a forum for emerging female artists to exhibit work among established industry names and by channeling resources to provide structured visual arts education opportunities for underserved girls in New York City and New Jersey. The exhibition and programming venue, Urban Zen, was formerly home to Donna Karen’s late husband Stephen Weiss’ art studio and has since been repurposed into a cultural venue honoring his legacy. Donna Karan, with her Urban Zen Foundation, aims to support preservation of culture around the world, bringing care back to healthcare, wellness, and education.

Said Karan of the partnership: “When I look at Mashonda and all that she is doing with ArtLeadHer, she’s connecting the dots between women, art and our community. She brings together the most beautiful artists, highlights their talent and soul. She’s raising awareness and inspiring change, and that truly expresses what Urban Zen is about – creativity, collaboration, communication, community and positive change.”

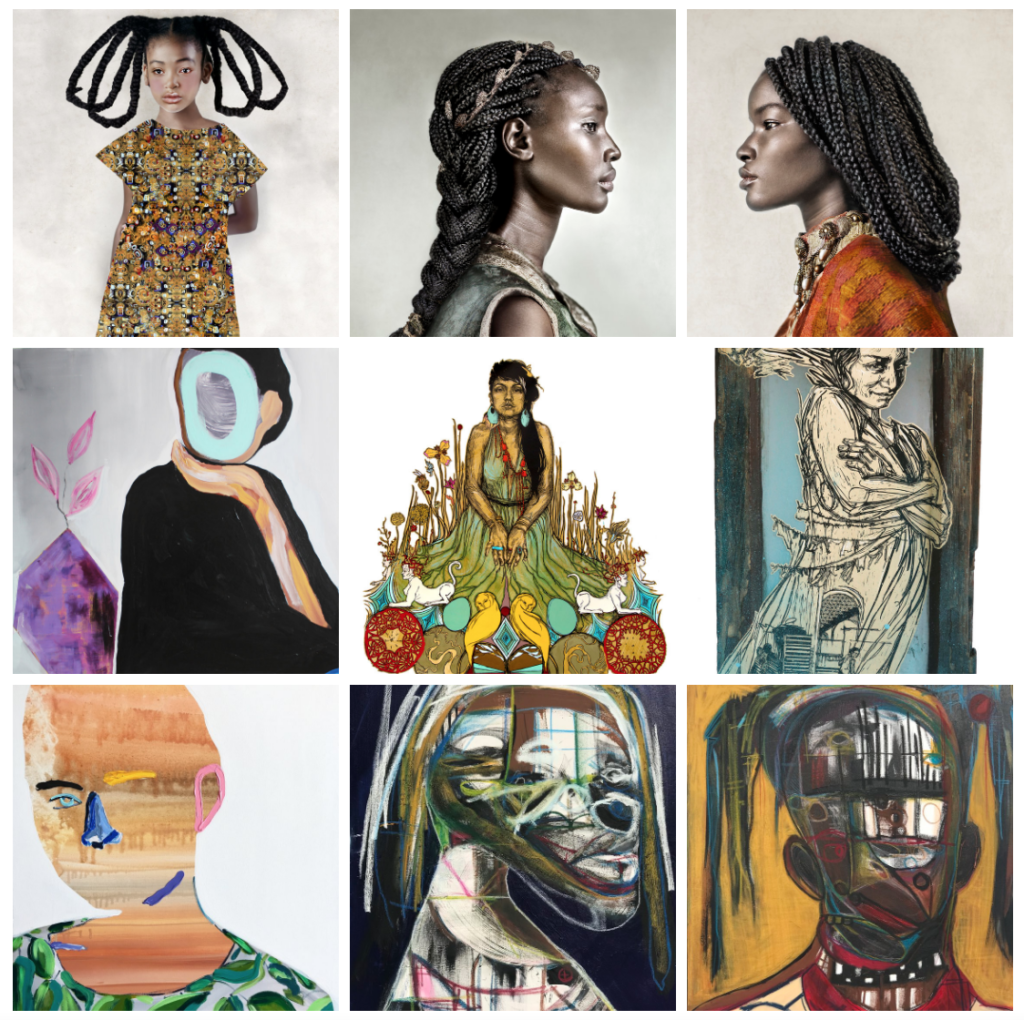

The exhibition’s title, King Woman, embodies Tifrere’s goal for the show: to highlight work by women and to celebrate those who question history and defy limitations. Artists selected for this show have found a way to project their own gender identity in a powerful and unabashed way, showing that women can be more than a Goddess or a Queen and are capable of being “King,” the pinnacle of power, strength, and skill. The exhibition presents works with a dynamic range of styles, including figurative work, traditional to digitally enhanced photography, hyper-realism, and explosive gestural paintings.

King Woman is on view at Urban Zen at 705 Greenwich Street until April 7, 2019 and features work from Genesis Tramaine, Swoon, Tawny Chatmon, Yulia Bas, and more.

Mashonda Tifrere: The goal is to definitely get to 50/50 but where would you say we are now?

CARMEN HERMO: It’s an exciting time. I think that we all feel that feminism is in the air and that our current political climate is causing a lot of institutions, collectors, and powerful people in the art world that maybe it’s not quite as active as in the 70s, but at the same time these same questions are being asked. I’d say today things are doing better in museums. We can see like last year in LA, there was something like six solo shows dedicated to women artists. We can see how museums are building it into their calendar, to highlight women artists in depth. But then at the same time you can see how there are still disparities. 70% of MFA students are women, but just about 40% of artists represented by galleries are women, so you can kind of see how the rubber sort of hits the road once it comes to being a professional artist and have your work seen and known.

This question is for you, Joeonna, what have been some of your greatest struggles and triumphs as a professional advocate for women artists?

JOEONNA BELLORADO-SAMUELS: I’d say some of my greatest triumphs have been working with specifically a few artists from the very, very beginning of their professional careers. Not even necessarily by representing them but just in terms of friendship, community, being another ear for them to process the way that they maneuver in the professional world and deal with their galleries even if they weren’t with me. But also, working with artists really closely from the very beginning and kind of helping them, usher them, doing what I’m supposed to be doing but also being able to see that arc of their career. It’s why we do it. So that’s been really wonderful.

I’m thinking about, when working with women artists, the constant struggle of thinking about their market. And that has been something that a number of female artists that I’ve worked with have expressed a lot of concerns about, that we have to combat this idea that their markets are always kind of behind their male counterparts. So that’s something that’s an active disappointment.

What do you think the number one thing that keeps them behind?

JBS: I mean there’s so many different factors in terms of where a price structure can be for an artist, so that’s a much broader conversation, but I think that it comes down to very simple micro and macro economic issues, in terms of supply, demand.

To mix it up a bit, since we have a lot of artists in the audience today, what are the key things any artist should take into consideration during a studio visit with a curator such as yourselves?

YSABEL PINYOL: Well yes, we do a lot of studio visits. Weekly, daily, constantly. That’s what we do. I really appreciate when I walk into a studio and there’s an effort of presenting the work to me. It’s very important that the artist has thought through how he or she will present the work and how will they talk about it. Recently there’s a lot of pressure on artists having to talk eloquently about their work, which is a little bit contradictory, because they are visual artists and don’t necessarily have the skills of writing and talking.

JBS: For me, I would like the artists to know that I’m a little nervous being in the studio also and I’m never quite sure what the artist’s expectations of me being in that space are. It’s important to have some questions or have an idea of what you want your experience in the artist’s studio to be. I’m never sure if this should be a critique, or is this just me listening, you try to feel it out. I hope that we can have a conversation about your work. I always pull back a little bit until I have a good sense of where they are and what they want to express.

CH: I co-sign all that. I think I like to have moments where you break it down and have a person-to-person conversation. I think it’s really great when you can get that sense from an artist that they’re proud or excited to tell you what you’re looking at. But it can also be kind of nice to just get to know each other more as people. Sometimes these are just the beginning of conversations and they continue for months or years. Keep in touch, update, also realize that our relationships can be really long as well.

JBS: One other thing is I’m super interested to hear what the artist is thinking about, not necessarily what is represented in their studio.

I have a question for each of you now. Joeonna, we can start with you. What are some of the key steps you’ve taken towards developing your most successful women artists like Nina Chanel Abney and Toyin Ojih Odutola? And how do you nurture those relationships?

JBS: All of the keys revolve around, to answer both those questions in the same way, is that I am their advocate. Kind of cliche, but definitely the truth. It is my responsibility and really my job to really support them. To do administrative things that they don’t need or want to be doing, to help guide them, to help strategize with them. And I would say recently – I won’t put the artist on blast – but something happened. She asked me to separate business from friendship. And we had a conversation about how that was just completely impossible. The artists I’ve worked with have become family and that’s certainly not how I think about how we have worked together for so many years. They’re one and the same, and they can be. It doesn’t have to be two separate things. And it shouldn’t. I would say in the most successful years of working with people, it’s because we’ve been such a team and such a partnership.

Carmen, as a woman curating women, what are you most mindful of when partnering with artists whose work represents biases?

CH: Of course, we are in 2019, and we can really think about how feminists have done great work and changed the world, but historically you can see how even feminists have excluded narratives, excluded people, made bad decisions, etc. I have really amazing conversations with a lot of my colleagues who are women, who sort of have this take that in 2019, it is also our responsibility to be able to say these are the artists that you should have been showing and thinking about. Where are they? That same question about representation that you brought to bare in the beginning. A lot of people probably know that Judy Chicago’s epic work of “The Dinner Party” is on view at the Brooklyn Museum. It’s totally the definition of a game-changer, for a lot of people it represents feminist art of the 70s. And it’s really from the 70s, there’s so many different ways to really enter that work, to talk about the lack of representation of women in history, the amazing use of ceramics and embroidery to talk about women’s work in art history, but then also see, too, how her biases as a white woman from upper-middle class background is warped into it as well, looking back on some of its limits and the questions it continues to ask us.

Ysabel, you were at one time a gallery owner at your home town of Barcelona. Is the atmosphere of women leading different abroad versus being in the states?

YP: I’ve only been in this country for 10 years, and only when I arrived here I was more concerned of all these feminist thoughts and so on. Where I’m from, Barcelona, Catalonia, it’s a millennial city. It was settled by Greeks, Romans, there are orphans from Egyptian civilizations. Egypt, at some point was very matriarchal, and I feel like there’s a lot of that you can see – not in Spain, but in Barcelona and Catalonia in particular. Port cities are used for immigration, they are open-minded. They are very entrepreneurial and women always have a lot to play in this part. I think that Barcelona definitely has a lot of visibility with women in politics, women in the arts, women in science. It’s just because of this historical background that maybe the region has.

How was it for you coming here and having to hear about and deal with the way women are treated so differently from you own experiences abroad?

YP: It’s still an eye-opener for me. Within these last 10 years, I’m like, oh, this is happening. Oh, inequality within race. Oh, Inequality within gender.

It’s drastically different.

YP: Very different. I come from the way I was raised and from my own experience.

So this question is to all of you. What’s been your experience with gaining support from women in your industry? Are women truly empowering one another in the art world and how can we be better?

JBS: I had the privilege of working with a lot of women, even from the very beginning of my professional career, and I would absolutely say that I was mentored heavily, always supported, always had a community of women around to directly work with. And even more than that, outside, women working in the field who recognize the need for that and made sure I was supported. And not working in isolation, understanding that as women working in isolation can allow you to continue to question what you’re doing and your values, and compensation and all these kind of things. What can we do? I think that we just have to keep that going and we have to be mentors, and we have to help our own communities and help younger women as they’re coming up to build their own.

CH: For me I was also lucky. Had great women mentors who, in some cases, didn’t spend a lot of time actively mentoring me, I feel like this is a different kind of mentorship, but really just modeled the hard work and dedication needed and I still draw so much inspiration and energy from the women in my life – from my mom to my colleagues, even from a lot of our interns. To see a lot of young people coming up in the museum, we have this great fellowship program, and I learn so much from them because they’re kind of like the cutting edge, in a way, so it can be really amazing to have those conversations. I also really believe in mentoring “laterally.” I don’t know if that’s a thing, but that’s what I tell myself it is. It can be so competitive and so busy, and it’s just great to take a moment and say: “Let’s get coffee and talk about your exhibition idea, I have some questions I want to run through you.” Reaching out to the people that are next to you, too, as colleagues is just really generative.

YP: From my experience at Mana, we’re pretty much 95% all women. We’re very good listeners – and I think that’s a huge asset that we have. We help each other, we’re very self-sufficient when the right tools are provided, so we make a great team.

Donna Karen: The thing that I’m really curious from all of you is are there any specific things you see between a woman artist and a man, and how do you define that?

JBS: No I don’t think there are inherent differences or characteristics. I always think it’s really interesting when people come into an art fair and people look at a work and immediately gender the artist without knowing anything about them. Obviously it stands out to me when they’re wrong. But it happens quite a bit and I think it’s really interesting to think about the ways that we look at art and how we plant gender on a color or figuration material, and the ways that those are used and employed.

CH: I think that’s a great answer. Especially that momentary assumption or thinking you know something about the artist. In the Feminist Center we have a show up right now called “Half the Picture,” a feminist look at the collection and it draws from the holdings of the museum and I always make the joke: “True warning. There are men in this exhibition.” And of course, it’s just a handful, like Vito Acconci, Andy Warhol, Käthe Kollwitz – really amazing powerful artists. And I feel like it’s been surprising for some of our visitors – the standout works are Nona Faustine, Wendy Red Star, Harmony Hammond – but to really think about, what does feminism look like? What’s this powerful political statement look like when it’s all of us saying it? When we think about the future of feminism – which we do a lot at the museum – we can learn from how women artists from the 60s and 70s were trailblazing and saying it’s okay for me to talk about my personal experience in my work. And you can see how the groundbreaking efforts that they made just sort of normalized art today. That shows too, an idea can come from a gendered experience, but artwork can speak to so many different people and inspire, like you were saying, you can’t really put your assumptions onto a work until you know where that artist is coming from.

YP: Yeah, I mean it’s exactly this. Feminism is about equality. So my question is: Is it good art or is it bad art? What makes something good? A genuine voice, right? What makes it bad? Just derivatives from so many other things. So that’s the way, at least, I look at art. I don’t look at the gender, I look at: Is it good, is it bad?

CH: I think it really is still important to do shows like this and have places like the Feminist Center, and to make sure you know that your gallery has a certain percentage of representation – so it is about equity and it’s about looking for the work for what it is, but also to realize we are dealing with centuries of inequality within the genders and it’s going to take work to really see that change.

MT: For me, as a collector, it’s never about “Do I like it because a man did it?” or “Do I like it because a woman did it?” It’s about how the work makes me feel and can I wake up every day and look at it? Can I pass it down to my children? I think when you look at it from that perspective, gender doesn’t matter.

Male audience member: As you guys continue to do the work that you’re doing to level the playing field for women artists, how, if at all, does that mirror some of the struggles that you ladies face when trying to break ground in the spaces that you occupy, especially because a lot of the spaces are male dominated?

CH: It’s a very real question, so I appreciate that. I’m sure we are all sitting here thinking about those awkward moments where we wish we could have ground our heel down on a collector’s foot when he was being inappropriate to our face. All those moments where you have to draw strength from within. So I feel like, as someone who gets to work across generations, I can see how much better things are, than someone like Judy Chicago who was told: “You need to choose between being a woman and an artist, you can’t be both.” We have come so far from that kind of blatantness to experience the small ways in which women are devalued. Also we see it playing out nationally, as well – but to kind of center that and realize that’s where the activation and ongoing work. I’m sure that’s sort of relatable to so many different kinds of experiences and backgrounds.

JBS: In terms of the workspace, I listen to women, no matter where they are in terms of the hierarchy. I give them credit for the work they have contributed, and I talk to women in other spaces and my own about compensation – I think that’s something that I certainly struggled with and wasn’t taught. There’s definitely a conscious thought to put those things into practice in a really concrete way. As far as the artists, I would say that I do dig my heels a little deeper for certain things the women artists are fighting for and facing, not finding support or expecting them to acquiesce to the way that things are and trying to move that forward somehow.

YP: I just had this recent experience with our fall program at Mana where we were representing ongoing exhibitions of Andy Warhol, John Chamberlain, Dan Flavin, Fred Sandback – and all of a sudden I’m looking at the program and I’m like: “Wait. These are all white men from 60s and 70s minimal conceptual art.” So we also curated this exhibition of female artists in New York from the 60s and 70s, like Judy Chicago, Dorothea Rockburne, Linda Francis, to make sure that we included all the voices.

Female audience member: I’m personally an advocate of UN Women’s “He for She” campaign. I think it’s really important that everyone is part of the conversation for equality. We need men standing up if a woman is not being included in an exhibition. So my question for yourselves is: What do you see the role of your male colleagues in this conversation to champion and represent women in “herstory” – history, of course.

JBS: To pay attention and do exactly what it is that we’re doing, and not expected to be patted on the back for that.

CH: Well said. Alliance is important but sometimes alliance can sort of feel like just a co-sign. It needs to be more active than that. It needs to be taking time out of your day, using your power, using your platform, to advocate for exactly what you were saying. You can see how male artists and male colleagues of mine are in it and want to be pushing that conversation forward. Unfortunately, there are still lots of people who will listen to them more than they will listen to us. That’s an unfortunate reality, but it’s important for all of us to move forward together. Not too many back pats, but encouragement and unity – solidarity, really.