What Would Marilyn Say? The Appropriation of Images in Contemporary Art

Comparing Emily Ratajkowski’s struggle on reclaiming her own image to Andy Warhol’s Marilyn series.

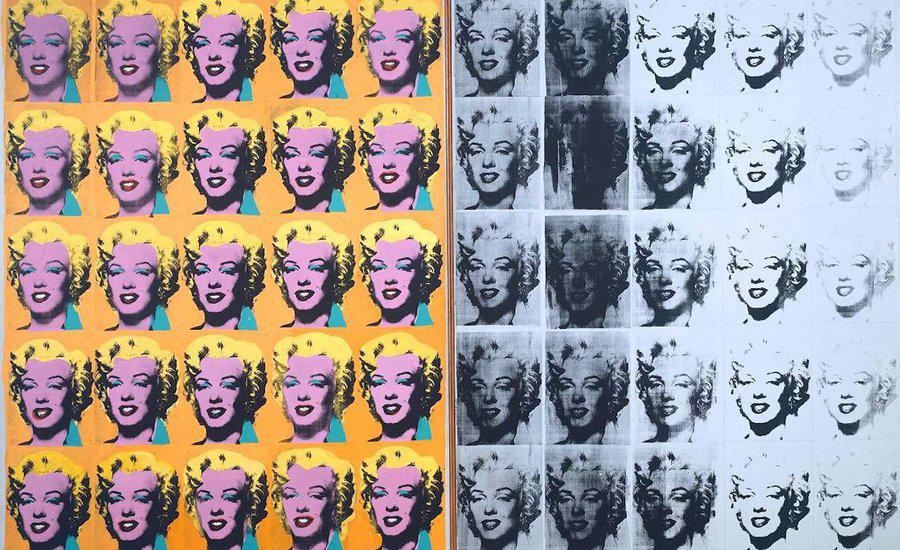

The more you look at the same exact thing, the more the meaning goes away, and the better and emptier you feel,” said Andy Warhol in regards to his repetitive images of pop culture icons like Marilyn Monroe. As I sat at my desk and read Emily Ratajkowski’s essay, Buying Myself Back: When Does a Model Own Her Own Image?, which detailed her struggle to reclaim her image from the grasps of art world giants like Richard Prince and fashion photographer Jonathan Leder, I was reminded of this statement by Warhol. We are constantly and relentlessly bombarded with images on our Instagram feeds to Facebook, to the art that hangs on our walls. With this barrage of images of predominantly women, we have forgotten that the body in the photograph is another human being with a right to her image, likeness and form. In this consumer society, women such as model and arts patron Emily Ratajkowski are reframing the conversation and speaking out—but I couldn’t help but wonder what Marilyn Monroe would say if she was still alive? What would the original pop culture icon think about Warhol’s famous work and the role she has played in the lives of female celebrities who followed in her path?

Ratajkowski is a super model with international fame and her image is easily recognizable by most people with a connection to the world of high-fashion and pop culture. Her likeness has been featured on the covers of VOGUE, Harper’s Bazaar, and Sports Illustrated but also in the “Instagram Paintings” of Richard Prince. Before reading Emily’s article in The Cut, I was oddly familiar with what she looked like nude, the size of her waist, and curves of her pouty lips. From this statement, most would assume I know Ratajkowski personally, even intimately, but that could not be more wrong. I am simply one of the model’s 26.6 million Instagram followers—a consumer of her image and her reflection. However, until I read her essay, I was not aware of what controversies lay underneath.

Female models and celebrities have been idolized in American society and culture long before Emily Ratajkowski—the most notable woman from this group being Marilyn Monroe, who was one of the first major sex symbols to gain international fame not for her professional career but for her body and image. Monroe, like Ratajkowski, fascinates on-lookers in such a way that they have obtained a near-mythical status. With this unparalleled fame comes a dark side in which photographers, artists and others believe they have the ability and right to do as they please with these women’s likeness as if they did not exist.

Warhol was a fame seeker, a mass-media worshipper, but most of all, he was a consumer of images. Inside the disco ball-laden dance floors of Studio 54, Warhol found the women who became his most beloved subjects. Women such as Liza Minelli, Liz Taylor, Debbie Harry and Joan Collins, all became the obvious crowd pleasers of Warhol’s oeuvre, but none were ever as famous or as seemingly important as Marilyn Monroe was to Warhol and his career.

Just as Richard Prince used a screenshot of Emily’s Instagram feed, Warhol reproduced a press photograph taken by Gene Kornman in 1953 to advertise the film Niagara starring Monroe. Both of the artists chose carefully curated images of the female stars. Emily’s Instagram feed is the contemporary version of Marilyn’s press photographs, images chosen for their highlight reel effect. However, the crux of the issue lies in the implication that the women featured in these artworks should feel a sense of gratitude, be faltered or appreciative of being “chosen” by these superstar male artists to be featured in their artworks. Little does the viewer of these works often know that the woman they are staring at in the work did not consent to the production and use of her image—their voices are not heard but their bodies are worshipped and consumed.

Emily takes this issue head on in her essay by stating: “It seemed strange to me that he [Emily’s boyfriend at the time] or I should have to buy back a picture of myself — especially one I had posted on Instagram, which up until then had felt like the only place where I could control how I present myself to the world, a shrine to my autonomy. If I wanted to see that picture every day, I could just look at my own grid.”

It seems obvious that the Instagram post should belong to her and not Prince, right? Why does Prince feel he has the right to reproduce Emily’s Instagram along with those of so many other female celebrities and social media stars? Even when Emily stands up and fights back, she is met with a hostile, male-dominated art world that tries to silence her disapproval, to tell her that her reflection is not her own, but theirs.

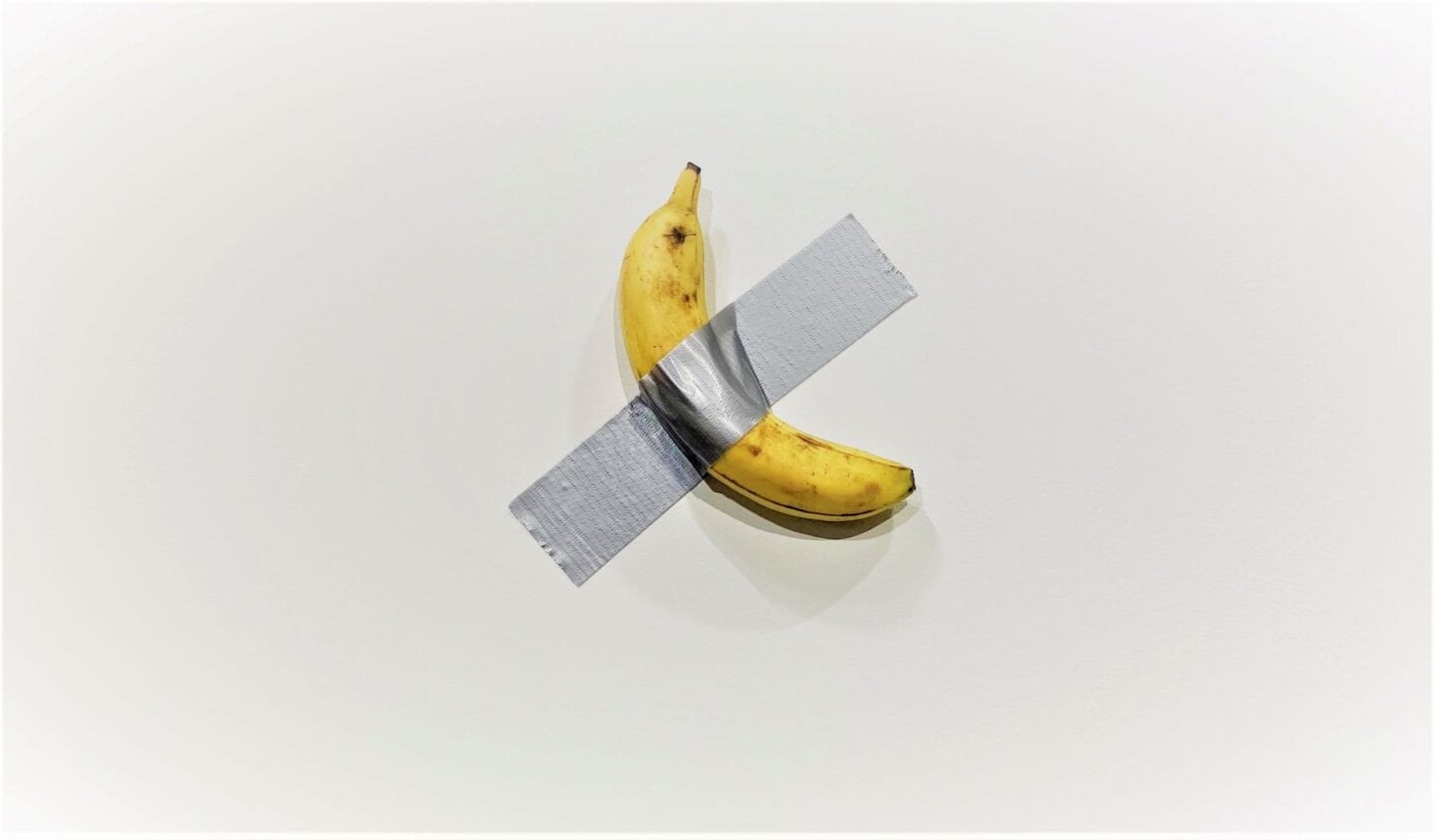

Male artists have long been viewed in a God-like way, as they seem to produce works of pure-genius out of thin air. White male artists, in particular, have often trampled on social norms and moral standards without question, rewarded with thousands of dollars and endless media hype. For instance, when Italian artist Maurizio Cattlan duct-taped a banana to a wall at Miami Art Basel in 2019, it was sold for an astounding $120,000 and featured on Page Six, being compared to Warhol’s iconic 1962 Campbell’s Soup Cans. In 2017, Jeff’s Koon’s Gazing Ball series was featured at Gagosian in Beverly Hills, dangling over various reproductions of classical masterpieces, including The Mona Lisa. As comedian Jena Friedman described in an article on Artnet: “Otherwise known as epididymal hypertension, ‘blue balls’ refer to the testicular pain that occurs after prolonged sexual stimulation without ejaculation. It’s also a great way to describe Jeff Koons’s current show at Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills.”

We, as a Western society, have created and allowed for the image of the struggling, angry and overly emotional male artist–allowing men the right to act in a deplorable manner in order to create “great” art, while female artists in the same right are often seen as radical or regarded with skepticism. However, when you say it out loud, this sounds ridiculous to the ears of women in the twenty-first century. Female artists, subjects, and muses are fighting back for the right to produce the truth about their bodies and their public image.

Women have been and continue to be viewed through the eyes of the unrelenting male artist who takes what they need from the female form–mostly our unique physical body parts in their most idealized form–and fashion them through their own desires. This creates serious societal and cultural repercussions as we as social beings take our cues from art, literature and the media. When these institutions publicly allow and proliferate women as viewed by men we end up with a society that believes a man has the right to a woman’s body without her consent.

From cat-calling, to physical harassment, women are the victims of the society men have created and when we fight back, like Ratajkowski did, we are met with scrutiny because we want to determine how we are depicted, a right denied to us for so long.

So, what would Marilyn say to all these reproductions of her image? How would she feel if she was alive today to see that she may be the most recognizable subject in the art world next to Mona Lisa? I am inclined to believe she would be shocked to see how her likeness, her image, her face is not her own just as Ratajkowski has so harshly realized. She is not remembered for her professional success but for her sultry gaze, voluminous hair and lips. Her own reflection gave Warhol international fame and stripped her of the opportunity to be more than a singular press photograph. Will the pattern continue or will women like Emily Ratajkowski lead the way to a different art world where women are compensated for the use of their images? I personally hope for the latter.