Maja Ruznic’s sensational exhibition, Name of the Voice, is currently on view at Hales Gallery, London until 24 October.

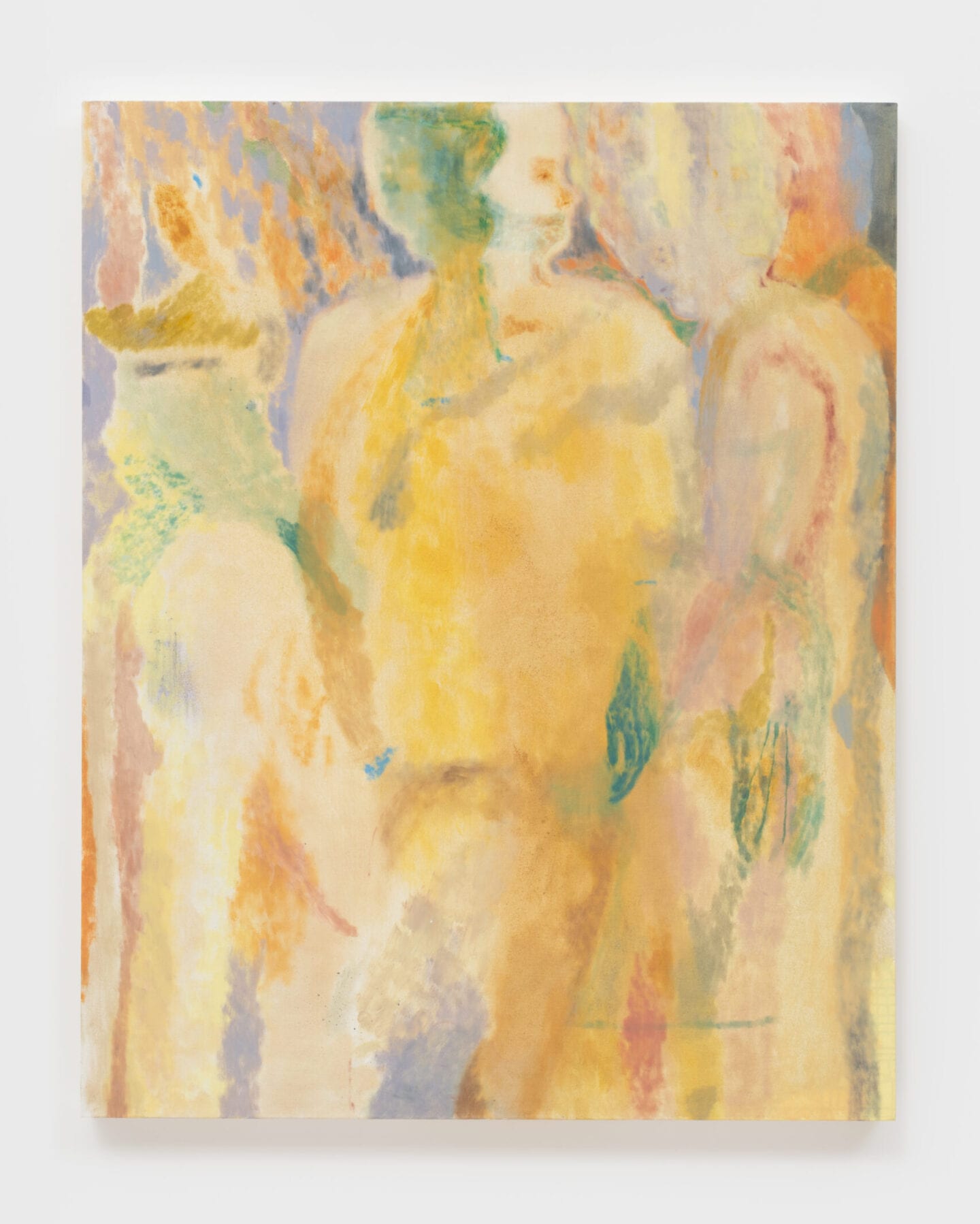

New Mexico-based artist Maja Ruznic paints her emotions and memories that explore identity, melancholia, and the human psyche. Ruznic’s paintings are soaked and stained with thin layers of oil pigment, exposing the canvas’ organic nature and rendering the works an airy watercolour-like quality. Born of the artist’s dream state, ethereal figures blend into one another across her vivid, abstract paintings, allowing enigmatic narratives to slowly emerge. Her swaths of pastel colours flood the picture plane with a translucent, spiritual rhythm.

Reminiscent of an Agnes Martin room, Ruznic’s current exhibition at Hales Gallery creates a sacred space for meditation. Her colour harmonies emanate outward, enveloping the viewer in a calming, maternal-like embrace. In fact, all of Ruznic’s paintings in this exhibition were inspired by her mother, with whom she escaped the Bosnian War, and spent three years in refugee camps in Austria. Ruznic and her mother eventually immigrated to the United States. She went on to study at the University of California, Berkeley, later receiving an MFA from the California College of Arts. Since then, Ruznic has exhibited internationally. She was a recipient of the Hopper Prize in 2018, and her painting was acquired by the Dallas Museum of Art in 2019.

Can you tell us about your background, and how your childhood has shaped you as an artist?

I was around 8 when the war started in Bosnia, and my mom and I fled the country. I was raised without a father so it was just the two of us for a long time. The war started in 1992 and during those years we lived in various refugee camps in Europe. We finally settled down in California in 1995. The biggest way my childhood has influenced my art is the sense of melancholia. The melancholy feeling that a lot of my works have comes from what I call ‘The Great Sadness’ that was always around when I was a kid. I think the fact that I was around a lot of grief, sadness, danger, and hunger at a really young age created a space in my heart and soul that makes me feel those things all the time, and I think they naturally make their way into my paintings.

Your dreamlike paintings weave together layers of abstract figures and narratives. What do they convey?

I think all my paintings in this show are about my relationship with my mother. I don’t usually think about what the painting is about before I start, but the painting ends up telling me something I didn’t know before. Often while I’m painting there’s a moment where I get really tender…I feel my heart open up and I almost get teary-eyed. But after a painting is finished, it’s not really up to me to decide what it’s doing. It’s up to the viewer to see it.

I do hear people say that my paintings make them feel a melancholy mood, which is important to me. I think we live in a world that is so positive that it almost seems superficial. I think there’s nothing wrong with sitting with emotions that are uncomfortable. The artwork can be a portal to what sits beneath the emotions that we first encounter. Perhaps there’s something beneath sadness, maybe it’s anger, and then maybe beneath anger is actually great joy. So I think the layers in my paintings represent the way our emotional and psychological space flutters in and out. I don’t think any person can maintain a feeling for too long, as emotions fluctuate so much on any given day. I want my paintings to evoke that sense of fluttering emotion, almost like a butterfly.

What is the inspiration behind your paintings?

The aspect of painting almost feels like a prayer. I go into my studio and I feel like it’s an act of devotion to mix my colours and to paint. My marks and the colours that I’ve chosen show me something about myself. Whatever the content is, it emerges slowly, through colour and form.

It’s important to me that my art creates a place where we can go and let our guard down, like a Buddhist temple or a church. Everything in the world is so polarized, and we’re so focused on who is to blame. I want my paintings to be a safe place for everyone, whatever your political or religious background. I’m reading a book right now called When Things Fall Apart by Pema Chödrön, and she talks about tonglen meditation, where you breathe in the suffering of everyone, and breathe out the desire for joy for everyone in the world. I want my paintings to convey that and provide a space for people to sift through their emotions. I think humans are more similar than we are different, and I would like my paintings to be a place where all the ways in which we are similar can exist.

We were very moved by your current exhibition with Hales Gallery in London. What is your favourite piece in this exhibition, and what does it mean to you?

The most important piece in the show to me is Mother (2020). I remember getting really emotional when I was working on it. A distinct memory came to me while I was painting the piece: when the war started I wasn’t with my mother, I was with my grandparents, and I hadn’t seen my mom in a week or so. But that day, she literally emerged from the fog. She had found us. I remember turning around and seeing my mom in the distance, feeling so happy and running towards her with my arms wide open. She scooped me up into her embrace and I remember smelling her. So Mother is about that memory of me being reunited with my mother, but I didn’t set out to make the painting with the memory—it came to me on its own. Those blues had a big impact on me—they opened up something for me like a third eye, making everything wide and spacious.

How do you achieve the watercolour-like effect in your paintings? Can you tell us about your creative process and the mediums you usually work with?

I spent 6 or 7 years only painting with watercolours, so I learnt all my techniques doing that. I would fill a jar with water and watercolours, and pour it on a piece of paper. I would let it dry so that stains would appear. I would then start pulling characters out of the stains. Afterwards, I started doing that with oil.

With the show at Hales, I used acrylic paint because I was pregnant. I would create buckets of diluted acrylic paint, pour them on the canvas and let them sit for a few hours. Then I would put the painting up, get a cup of coffee, and just stare at the stains. Based on that, I would start pulling out things that I saw emerge—like a stain would dry and it would become the shape of hand, and that would be my starting point. I would then start using oil paint to articulate that hand. My colours are very diluted as I use linseed oil and wax. I don’t think of my paintings as layers of paint, but rather layers of stains. The stains create different shapes, and overtime those shapes start to take on the form of people or backgrounds or veils.

Tell us how you choose the colour palette for each painting. Do you associate certain colours with specific emotions?

The palette of the works at Hales is very emotional, perhaps because I was pregnant. There are a lot of blues in the show. Blue is a really sacred colour for me. That ultramarine blue, with a bit of titanium white, and cobalt blue—it does something to my psychic that feels like an opening. For the new body of works that I’m currently working on, I pick up things on my hikes, like a leaf or a feather or a rock, and bring them back to the studio. I then mix my palette based on the things that I saw outside or collected. I really love the palette here in New Mexico, all the colours are so subdued and dreamy.

Tell us about your artist studio. How would you describe the space and the way you work in it?

Now that we have Mila, our two-month-old daughter, I use my time very differently. When she’s sleeping and my husband Josh is in the house, I go to my studio which is just outside. It’s huge, airy, and beautiful. I feel really comfortable in my studio in a way I have never felt before. When I was living in LA I was always painting in shared spaces, which don’t feel very private. So I think having a beautiful and big studio has affected the kind of work that I make, because I know I will never be interrupted. It feels very cozy and spacious living in New Mexico too—everywhere I look there are trees. As a child who grew up with a lot of turmoil and trauma, I really appreciate this calm space which allows me to make the best work that I can.

Are there any artists who have especially inspired you?

My two main influences are Mark Rothko and Édouard Vuillard.

I saw a roomful of Rothko’s at the Tate Modern years ago, and that had a profound effect on me because I could see the weave of his canvases. Since then, I decided I didn’t want to use too much paint because that would hide the texture of the canvas. When you can see the canvas you can feel that the painting is breathing with you, and the canvas takes on the form of a spiritual being. The lightness of my paint has a lot to do with my desire to evoke a sense of breath in my paintings.

I love Vuillard because his paintings look like tapestries. I did some research and discovered that his mom was a seamstress, and he spent a lot of time around her when she was mending clothing. I feel like my attraction to Vuillard comes from spending many of my own young years next to my mom while she was repairing clothing. My mom repairs vintage garments and then resells them. I feel like there must be a connection there.

A more contemporary artist that I love is Cathy Wilkes. She’s an Irish British artist and she represented the UK in the last Biennale. There’s a beautifully emotional quality to her installations. She creates domestic scenes from which you get a sense of motherhood and memory. Louise Bourgeois is another big influence, particularly the psychoanalytical aspect of her works.

What advice would you give to your younger self?

My younger self was very worried. I studied psychology and art in college, and I was very confused when I graduated. A lot of my friends were moving to New York and getting internships, but everything for me happened a lot slower, and I was a bit depressed about my lack of direction. So I wish I could tell my younger self that everything will work out. Although I always felt like a loser compared to my friends who were getting corporate jobs, I always had a very strong conviction in my heart that I was an artist. I had a corporate job for two weeks and I quit because my soul was dying. So I would tell my younger self that I am so proud of you for quitting that corporate job, and not be so down on myself for not moving as quickly as some of my peers.

Can you share with us any exciting plans or goals you’re currently working towards?

I have an upcoming show at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, New Mexico, in March 2021. This will be my first museum solo show. The museum also has a beautiful Agnes Martin room, so it will be such a treat to have my works hang in the same space as hers.

I’ve also started making some drawings since Mila was born, and I call them ‘When Mila Sleeps Drawings.’ I’m going to have something exciting with these drawings with my New York Gallery, Karma, in the fall.