Penny Slinger: Tantric Transformations

London born, LA-based artist Penny Slinger celebrated female sexuality in a solo exhibition at Richard Saltoun Gallery earlier this summer. Sex, surrealism, and tantra merge in her work to create a sensuous experience of womanhood and discovering the conceptual self.

From June to August, the work of self-proclaimed “feminist surrealist,” Penny Slinger, adorned the walls of Richard Saltoun Gallery in Mayfair, London. The solo exhibition, Tantric Transformations, marked Slinger as the fourth female artist hosted in the current Richard Saltoun 100% Women campaign. This is a twelve-month project, launched in March that “aims to redress the persistent gender imbalance” in artist representation seen throughout art history and still prevalent in museum spaces today. Richard Saltoun, Gallery founder and director, takes pride in having “achieved gender parity in our roster of artists – 50% of the artists we represent or exhibit frequently are women.” Yet, 100% Women further protests a louder incentive for female artist recognition in the yearlong dedication to an exclusively female exhibition program, as well as wider events such as artist talks and film screenings. Find out more on Twitter and Instagram using #365daysofwomen.

Slinger’s art; criticised as porn, praised as self-expression, is best described as an exploration of female sexuality. Fitting to its context of creation – the 1970s were a period of radical feminism – Slinger utilised daring artistic mediums that ranged from collage to sculpture to Xerox print, to enable her own body as implicative of her womanhood. As one wanders through the exhibition, it becomes clear that Slinger is both artist and muse.

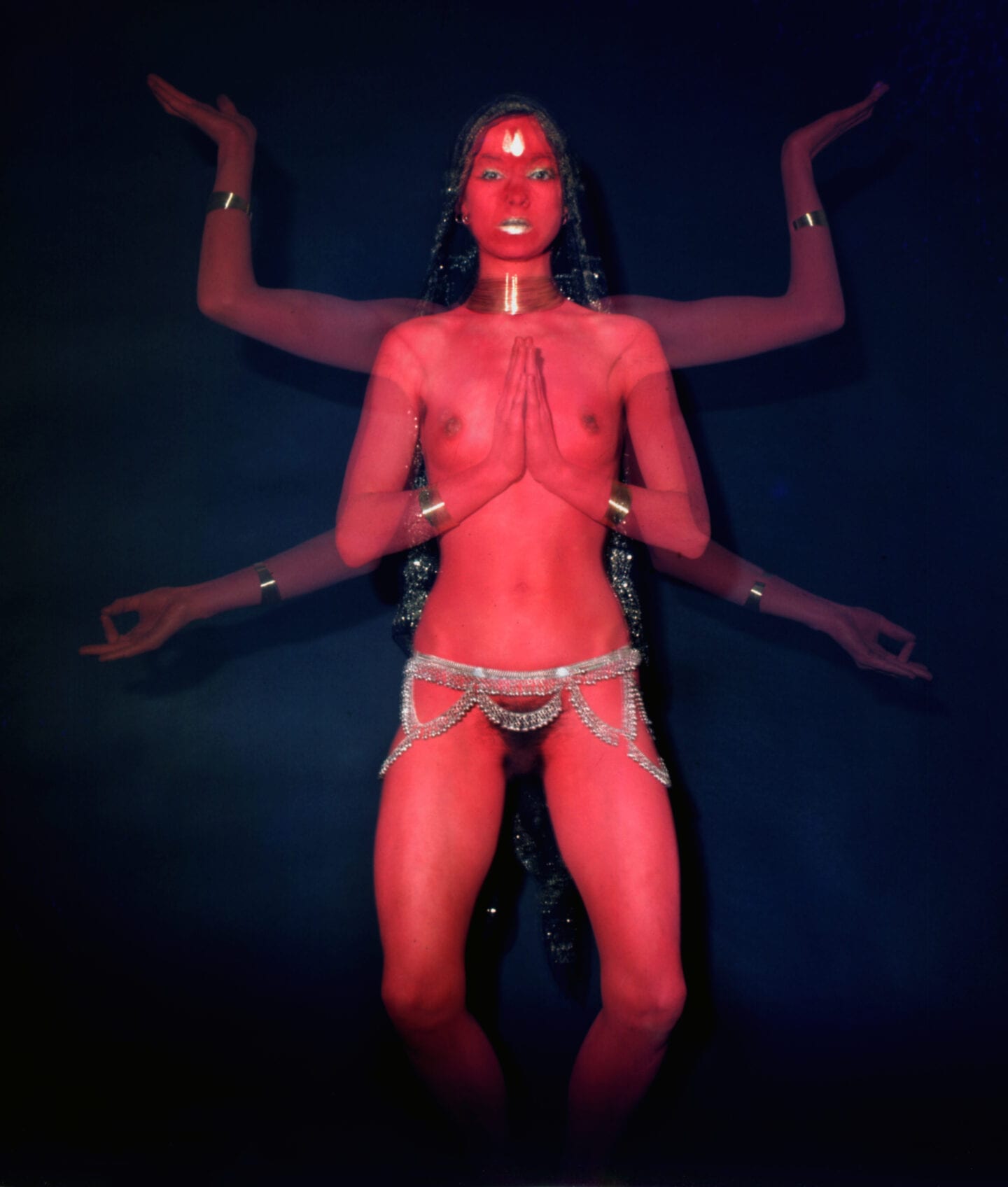

In deciphering Slinger’s unique style, which one may delineate as an amalgamation of surrealism, female sexuality, and tantra, there seem to be notable events that formed Slinger’s artistic gusto. Firstly, in 1969 Slinger was introduced to German Surrealist, Max Ernst, who arguably influenced the abstraction in her artwork. Then, in 1971, Slinger visited an exhibition at Hayward Gallery, Tantra, the Indian Cult of Ecstasy, to which she wrote that, “I saw a Yantra (mystic diagram) dedicated to the Goddess of Kali and understood abstraction for the first time.” From that moment, tantra infiltrated into most of her artwork as expressive of her femininity and the conceptual self. In both Surrealism and Tantric art, the mode of representation is understood as transformative, as if, in abstracting the artwork from realism, and dressing an image of the self in tantric iconography, a psychoanalytical understanding of female sexuality is revealed.

As stated by Slinger herself, “I’m more interested in the nature of the psyche, of stripping not just the naked body but seeing what’s going on underneath”. It has been claimed that Slinger’s artwork awakens the desires; the erotica in her work prompts a perverse enticement into one’s own repressed desires that echoes Freudian theory. Similarly to Freud, Slinger explores sexuality as a dissector into the unconscious. In a 1973 article in the women’s magazine, Spare Rib, Laura Mulvey, who is a British feminist film theorist and contemporary of Slinger, critically analysed Slinger’s exhibition, Opening, at Angela Flowers Gallery. The exhibition had a central theme of orality, which Mulvey deduced as a libidinal fascination of the mouth, in this regard, she disputed Slinger’s artwork as representative of the unconscious development of a sexual identity initiated by the Oedipus complex.

To quote the article, Mulvey said that, “phantasy persists in the traces of an unconscious desire” through which Slinger “showed us how powerfully a woman is able to transform surrealism” to uncover these desires.

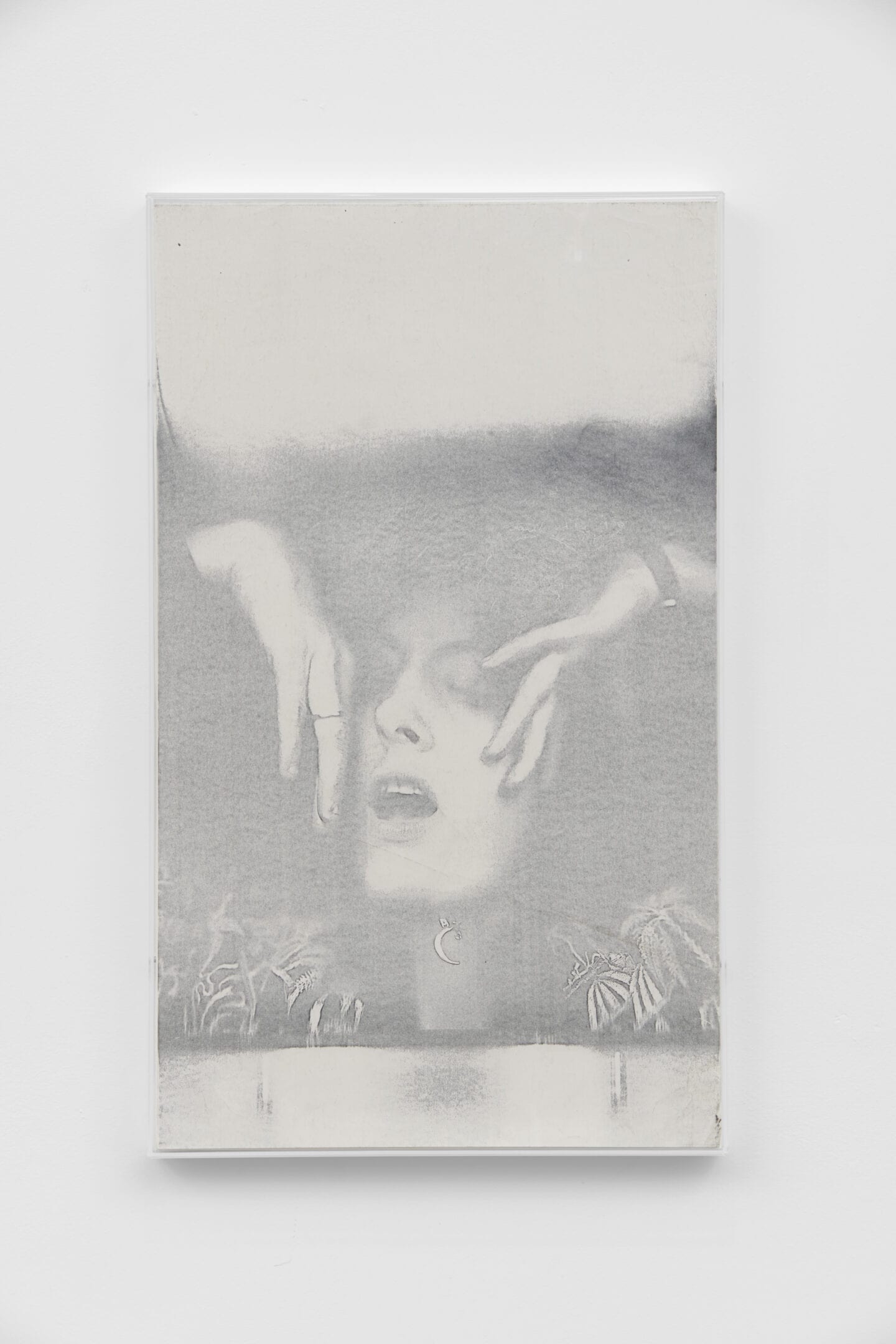

Scrolls, 1976

Photo by: Tayla Sapseid

In this respect, a psychoanalytical interpretation of Slinger’s 1976 piece, Grapevine, exhibited at Richard Saltoun Gallery, arguably reverberates Mulvey’s claim of Slinger’s libidinal fetishism upon orality. The abundant presence of grapes covering Slinger’s body promotes a sensory taste of her sexuality, accentuated by her tongue that further points the viewer to the theme of fetishist edibility. Mulvey claimed that “in the Freudian concept of phases of sexual development, the oral phase, which is the first, is dominated by the mother,” the child’s “main pleasure is in receiving nourishment” from the mother. In this way, Slinger’s surrealist expression of oral fetishism may hark back to her repressed pleasure of orality in infantile sexuality that has transpired as oral phantasy in the unconscious as an adult. It is by means of abstract surrealism that she portrays this fixation on orality. However, on another note, one could question whether surrealism, which is an attempt in accessing the unconscious, can truly represent one’s unconscious desires, if the psychology of the unconscious relies on repression to exist?

Slinger pushes the boundaries in this piece as the grainy photocopy tone against the rich purple of the grapes further stimulates the sensuality of taste, whilst the arrangement of the fruit is arguably suggestive of spiritual offering despite the obvious nudity.

Slinger’s earlier 1974 pieces in her collection, ‘Spirit Impressions’, depict her face printed on a copy machine during her career at Portsmouth College of Art. These later inspired a collaging of Xerox print and monoprint on silkscreen where she created scrolls such as Grapevine in 1976. Today, she has reworked some of her older pieces in digital photo collaging to form her Penny Red Dakini (2019), the tantric representation of full self-enlightenment. This maturation of artist medium from photocopy to digital collage, compliments Slinger’s maturation of conceptual self in tantra, which she shows as she identifies as Red Dakini. This suggests a development in selfhood throughout her art practice, leaning to the idea that iconographic abstraction and surrealism can serve to uncover one’s unconscious. Certainly, in researching Penny Slinger, it is clear that her work is as audacious and loud today as it was in the 1970s. Slinger’s demand for femininity and sexuality in one representation respects woman as a sexual and spiritual creature, when for so long women have been the objects of sexual desire, Slinger portrays the desires of female sexuality.

Having joined the first British all-women theatre group, Holocaust, in 1971, and resultantly, contributing to films such as The Other Side of the Underneath, alongside Jane Arden, Slinger was a multi-disciplinary artist for her time. Accordingly, during her solo exhibition, Richard Saltoun Gallery aired a private viewing of Richard Kovitch’s 2019 documentary of the artist’s life, Penny Slinger: Out of the Shadows. Having only been released this summer, it is a must see to gain a full image of the wondrous Penny Slinger.