Faith Ringgold: American People

A long overdue retrospective dedicated to Faith Ringgold has finally opened at The New Museum in New York, and is the most comprehensive exhibition to date dedicated to the groundbreaking artist’s vision.

Artist, author, educator, and organizer, over her 40 years career Faith Ringgold has been able to link the multi-disciplinary practices of the Harlem Renaissance to the political art of young Black artists working today.

Despite predominantly starting from a genuine narration of her experience as a woman, mother and artists of color in the United States, her work has been able to amplify the struggles for social justice and equity of an entire community and unmask well before the Black Life Matters movement some of the complexities of American identity that the country still had to address.

A few weeks before the end of the exhibition, we sat down and discussed about it with its curator and New Museum Artistic Director, Massimiliano Gioni.

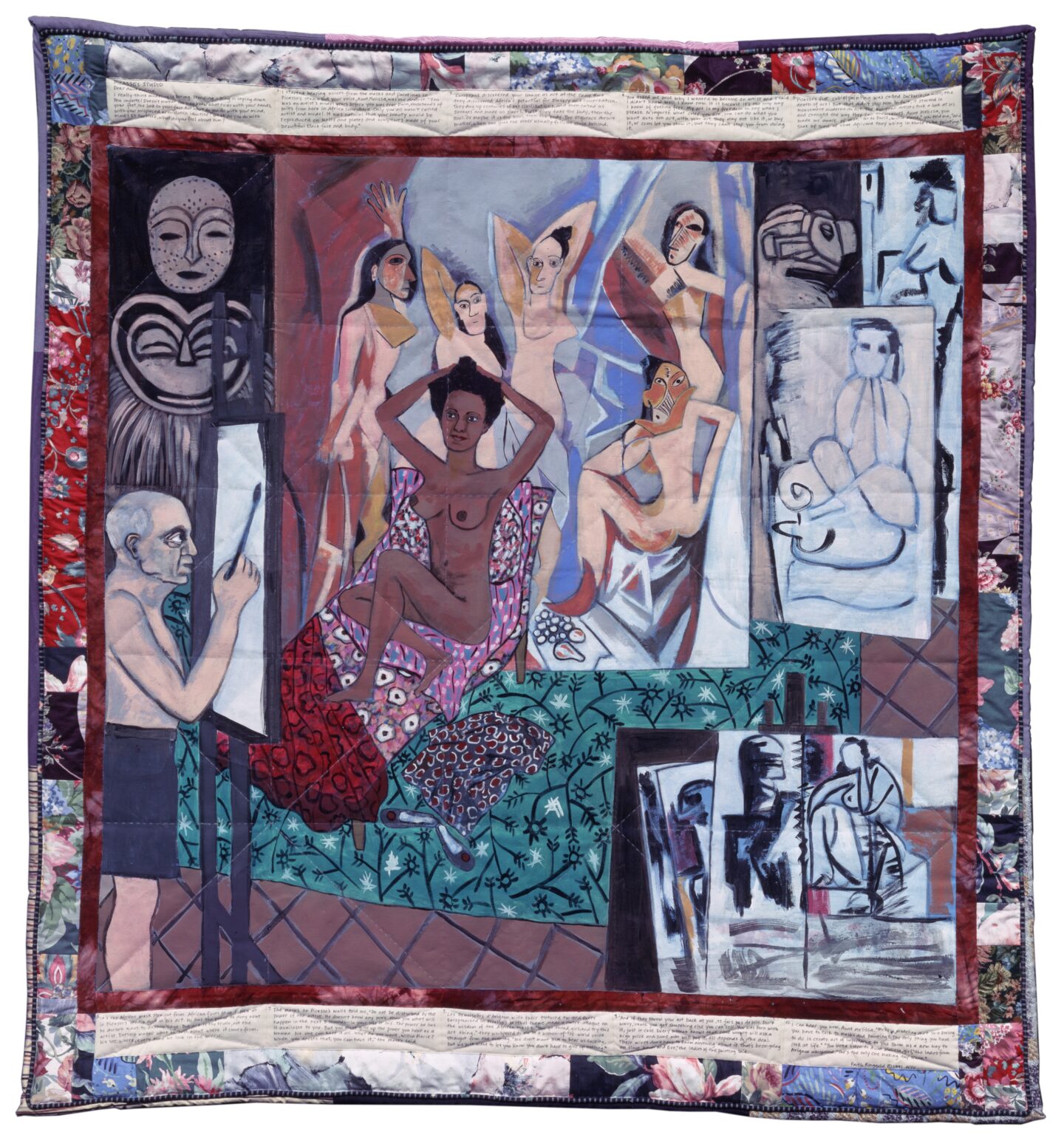

Although Faith has been one of the most influential figures in American art of the last century, her role (as many others) has just recently started to be fully acknowledged. A major step was MoMA’s epic decision to show her work from the “American People” series right in front of Picasso, with its expansion and rehanging of the permanent display.

That said, I think that the title of the show is quite significant, and beyond the direct reference to the series further attest Ringgold’s role in American art history. Can you tell us more about the reasons behind this specific title?

American People Series #20: Die did become somewhat famous after its inclusion in the reopening of MoMA in 2019—but despite that, not many people had seen Ringgold’s American People Series in depth. It was also the title of Ringgold’s first exhibition outside of Harlem, which took place at the cooperatively run Spectrum Gallery on 57th Street in late 1967. On top of this, we felt that the title American People really embodied the full show: her revolutionary work is so important to the understanding of the civil rights, Black Power, and feminist movements. These cultural shifts drastically changed the fabric of American history and thus of the American people. In her early work made during the 1960s and ’70s and all the way through the 1990s with her series The American Collection, we really see how she experiments with methods of rewriting or reconstituting American history from the perspective of Black Americans–especially Black women

Ringgold’s six-decade practice is so multilayered and rich of themes. Is there any particular curatorial approach you’ve decided to adopt in putting together this extensive retrospective, and in organizing the works into sections?

We’re known for giving the first major New York museum shows to both emerging and established artists—for example, not long ago we presented Hans Haacke’s first New York solo show since the 1990s. This coming summer we’ll show Robert Colescott who hasn’t had a show in New York City since the late 1980s. Here we had a national treasure like Faith Ringgold who had not yet received the institutional recognition she deserved in her own native city of New York. It was since the late 1990s, that Ringgold hadn’t had a show in New York and we liked the fact that her very last museum show had happened at the old New Museum, on Broadway, back in 1998. Before then, her last institutional show in New York had occurred at the Studio Museum in 1984.

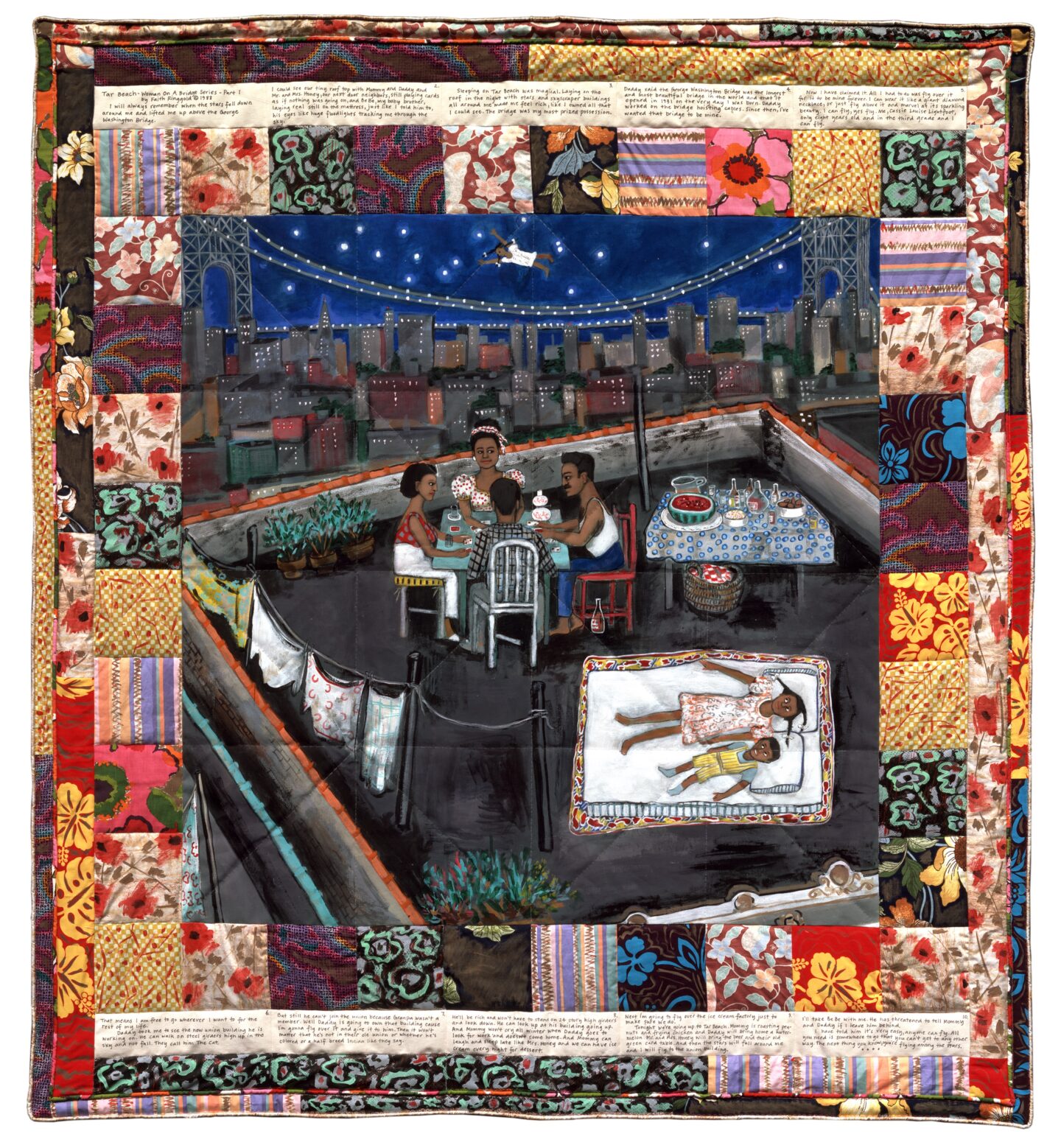

Ringgold’s work is unique in that it reaches well beyond the confines of the art world—she is not only a great, legendary artist, but she is also a writer and an educator. Like many of the artists we present at the New Museum, her work is crucial to understanding not only the history of art but the history of America. Completely disregarding and reinventing traditional definitions of “taste,” Ringgold blurs the lines between high art and craft, between accepted hierarchies and subversive practices. These are just a few reasons why we needed to make this wonderful show. And then also there was Tar Beach: who hasn’t read Tar Beach?!

In terms of organizing the show, I am a bit of a completist and a little obsessive. I am a maximalist; it’s in my name… So the idea of bringing together her 1967 three murals from the American People Series (Die, The Flag is Bleeding, and U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power) for the first time in a New York museum since they were shown together at the Studio Museum in 1984 was just too thrilling. And we set out to bring together many other examples of Ringgold’s work from different moments in her career, attempting whenever possible to display complete bodies of work and series. We didn’t succeed for each and every series but we were able to go quite deep.

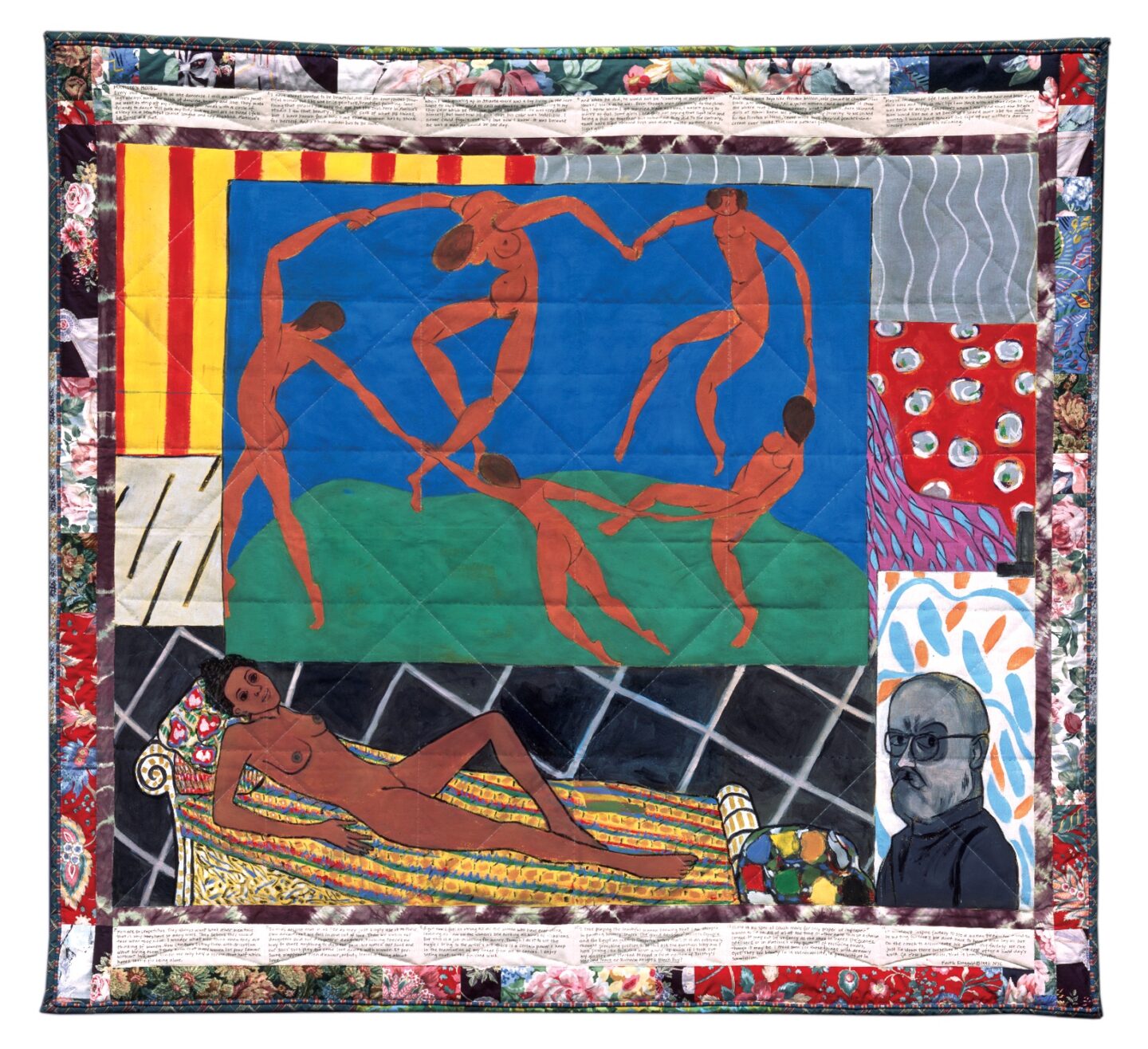

So, for example, this show marks the first time The French Collection has been brought back together in its entirety since 1998, nearly a quarter of a century ago. The American Collection is almost complete and series such as The Bitter Nest and Black Light or American People are shown in great depth.

“Faith Ringgold: American People,” 2022. Exhibition view. New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy New Museum. © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2022

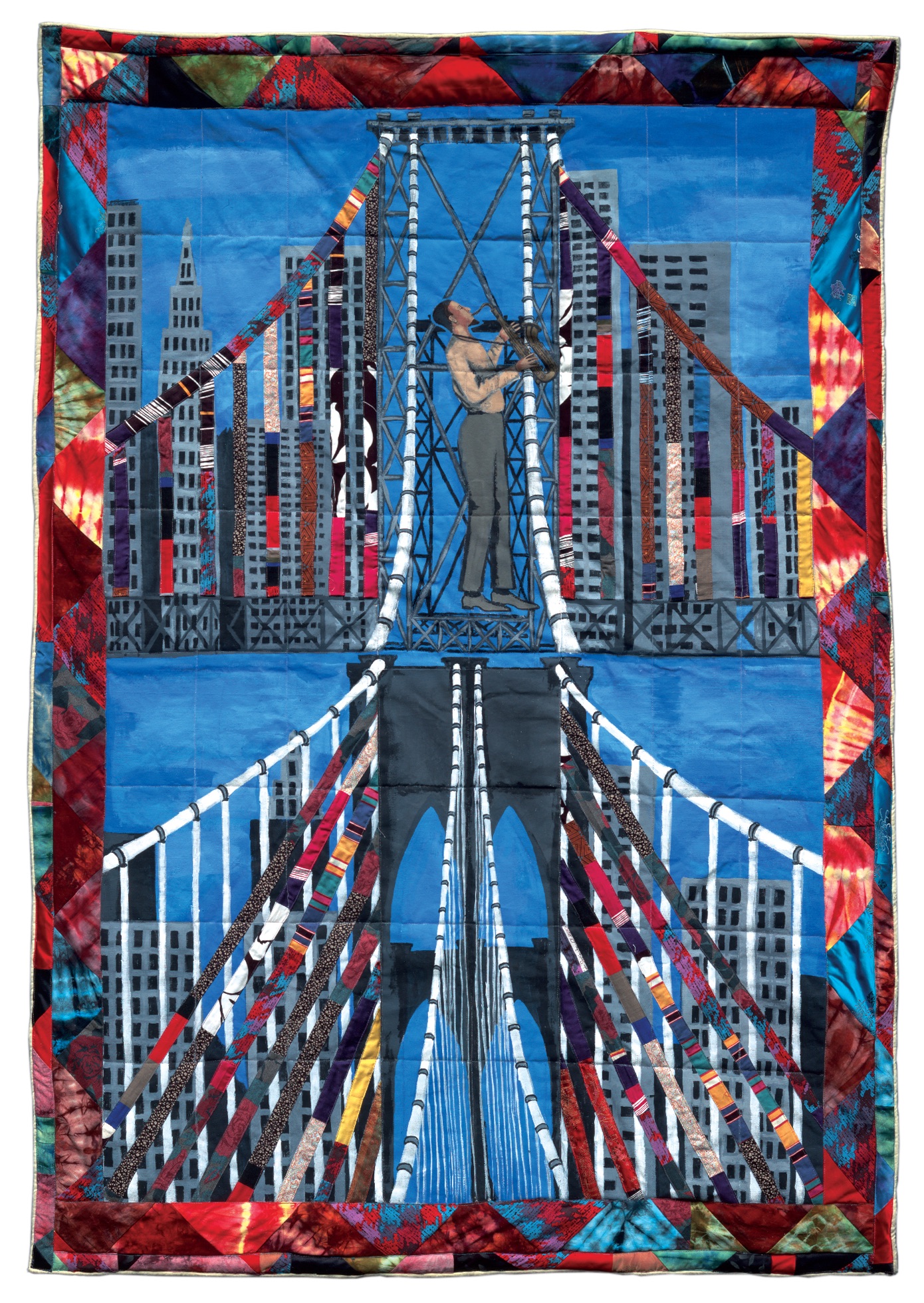

We also wanted to highlight Ringgold’s lesser-known work in sculpture—which she wonderfully described as “soft sculptures.” What a subversive use of terminology, when compared to the hard and obtuse sculptures of her mostly male Minimalist contemporaries… Together with her work with quilts, textiles, and fabrics, this sculptural body of work reveals Ringgold as the revolutionary artist she has always been, determined to deconstruct ideas around craft and hierarchies of aesthetics and power.

Finally, together with the exhibition’s co-curators Gary Carrion-Murayari and Madeline Weisburg, we also wanted to think of Ringgold as a writer—not only as the author of celebrated children’s books, but also as an experimental writer who, in her story quilts, has anticipated conversations around auto-fiction and what today is referred to as “critical fabulation” or “speculative fabulation”—a way of rewriting the past at the intersection of fiction and historical research. Throughout her work as an artist and as a writer, Ringgold emerged as a consummate storyteller who has stressed how important it is that we understand modernism and 20th century culture as a polyphony of voices rather than a monolithic and monochromatic history.

“Faith Ringgold: American People,” 2022. Exhibition view. New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy New Museum. © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2022

In many of her works Faith Ringgold addressed without filters the complexities of the American experience, but always starting from a distinctively personal perspective as woman, mother and artist. Which kind of issues do you think that she was particularly able to address in her works, and how were those tackled from a distinctively feminine perspective?

Ringgold both shaped and was galvanized by the Women’s Liberation Movement in the early 1970s and has consistently brought a feminist–more so than feminine–ethos to her work. In the very early ’70s, she started working with textiles and other craft-based techniques–fields long associated with “women’s work,” and thus, deemed lesser, unworthy counterparts to painting and sculpture. For Ringgold these artistic methods were to be read against the backdrop of the Feminist movement–they were an expression of her politics, which were always a tight combination of the personal and the collective. I love how she has often said she started working on unstretched fabric because she didn’t want to wait for her husband to come home and help her move the large canvases. Such a candid declaration of independence that is both almost confessional and very private but so immediately political…

In the 1970s, Ringgold also became very active as an organizer for a number of political causes aligned with the goals of the feminist movement. In the New Museum exhibition, visitors can see documentation of her organizing work with feminist groups including Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation (WSABAL), the Ad Hoc Women Artists’ Committee, and Women Artists in Revolution (WAR), who fought to make New York City museums more equitable for women and artists of color. This type of activism didn’t just end in the 1970s; her feminist perspective has been a mainstay of her entire career.

“Faith Ringgold: American People,” 2022. Exhibition view. New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy New Museum. © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2022

All these major retrospectives require a lot of research work behind. What was one of the most unexpected aspects you’ve discovered about her as a woman, and about her as a woman artist, while diving into all these materials?

I think one of the aspects of Ringgold’s life and career that is astonishing–more so than unexpected–has been her ability to constantly find new, and sometimes unconventional, avenues for getting her work out to the public, which is something you really see when you study the full trajectory of her career. Before she showed in commercial galleries on 57th Street, she was exhibiting art in Amiri Baraka’s traveling art caravans in Harlem. In the 1970s, she began circulating “traveling art” trunks with soft sculptures and textiles, which were essentially portable exhibitions that she would send around the country to university galleries. This brought her an entirely new audience outside of New York. In the early 1990s, she began a brand new aspect of her career as a children’s book author after the success of her 1991 book Tar Beach. With her children’s books she secured new audiences and reached out well beyond the confines of the art world, becoming a beloved author, a consummate storyteller, and a little bit of a celebrity really. Her perseverance is incredibly inspiring and the way in which she has created a new art world for herself, for her peers and for many women and for many Black artists, it’s just remarkable.

Being her mother a fashion designer and at the same time reconnecting and elevating the strong traditions of Quilts in African American communities, Faith has also largely worked on textile works. What’s the relationship between this side of her production, and her paintings? How is the choice of using this medium also relating to her being a women artist and her personality?

As you say, Ringgold’s mother, Willi Posey, was a fashion designer and dressmaker, who taught her daughter how to sew as a child. They actually worked together on art works for about a decade between the early 1970s and early ’80s, when Posey passed away. Within the Feminist Movement, new notions of authorship, collaboration and collectivity played an important role, so it’s interesting to think of Ringgold’s work with her own mother as part of a revision of conservative and traditional ideas such as that of the solitary, and typically male, genius.

Ringgold’s art is full of mother figures and matriarchal myths and matrileneal histories.

Quilting does indeed have a significant history within African American communities: for example, in the mid-nineteenth century, “quilting bees” were popularized as a social event during which women came together to talk and stitch quilts in collaboration with one another. During the civil rights movement, Black women, such as the women associated with the Freedom Quilting Bee in Rehoboth, Alabama, formed quilting cooperatives as a way for poor artisans to earn independent forms of income. Ringgold’s work fuses these interests in history, family, and politics across mediums.

Ringgold has been a fervent feminist and actively participated in the debate about identity politics, and of course racial discrimination. Which are some of her most revolutionary works resonating with her activism, and where, you feel, has been her greatest contribution in the debate around these issues?

In the show, you’ll see a selection of ephemera—press releases, fliers, letters, speeches, and posters—from the many interventions, protests, and presentations at openings and events where Ringgold advocated for reforming museums so that they could reflect the complexity and richness of American culture. It is no exaggeration to say that Ringgold’s has had a heavy hand in transforming institutions from the inside out, opening doors for many generations of artists to come.

“Faith Ringgold: American People,” 2022. Exhibition view. New Museum, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Courtesy New Museum. © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2022

Last, but not least: what distinguishes Faith Ringgold practice from other colleagues working at the time on similar issues, and what’s the legacy that she’s leaving to the generations of artists, and women artists of colors in particular, that look up to her work (i.e. Tschabalala Self, among the others)?

Ringgold’s influence is extremely far-reaching. In the gallery that brings together Die and The Flag is Bleeding and her Black Light Series, I can’t help but think of artists like Kara Walker, for her use of violence and her subversion of racist stereotypes, or of Glenn Ligon, for his use of language and his reference to music in his aesthetic and existential explorations of the colors blue and black. When it comes to textile works, younger artists such as Tschabalala Self and Diedrick Brackens come to mind. And her influence is not limited to the work of Black American artists. When I look at her works on fabric from the early 1970s, I can’t help thinking about the artists within the Pattern and Decoration Movement—a group of mostly white artists, who sought to deconstruct the rigor of conceptual art and the orthodoxy of postwar non-objective painting through craft, reimagining abstraction not as the province of European modernism but rather as a language that had emerged from minor arts, which, not accidentally, have been often very much connected to specific histories of gendered and racialized labor. In looking at some of Ringgold’s quilts and fabric works, I’ve also found myself thinking of an artist like Mike Kelley. Ringgold, long before Kelley, saw blankets, quilts, and textiles as charged receptacles of desires and anxieties as well as simple tools for protection and care.