Helene Schjerfbeck: A Portrait of Finland’s Forgotten Icon

After 130 years, The Royal Academy in London is giving one of Finland’s greatest modernists a long overdue solo show.

Upon hearing the name Helene Schjerfbeck, many will confess their unfamiliarity. However, ask the majority of people from Nordic countries, and they will observe her as one of the finest icons of Finland’s art history, who is criminally ignored in Western circles. Now for the first time in 130 years, the Finnish Painter has her first solo London exhibition at the Royal Academy. Schjerfbeck, who produced over a thousand works of art in her lifetime, has finally achieved recognition in London, with a retrospective exhibition ranging from naturalistic subtlety to brutally honest self portraits.

The child of an office manager in Finnish Railways, Helene Schjerfbeck was born in 1862. She broke her hip at the young age of four, an incident that left her permanently lame. She was unable to attend school and spent much of her childhood as a lonely child in silent country rooms, a setting that became a lifelong subject of her paintings. Her relief, she wrote, came with the presence of some pen and pencils – the gift of “the whole world”

Despite her ill health, Scherjbeck was widely travelled, commuting frequently to Paris where she was known to indulge in tremendously stylish fashion from Galeries Lafayette. She was famed for wearing vividly colourful tailored coats, high collars and fine jewellery. This expensive taste rarely made its way into her art, which focused on the more grounded aspects of a quiet society.

In her early twenties, she travelled to Cornwall in England, where she met an artist, only ever referred to as “the Englishman.” They had a brief relationship, yet he refused to marry her, citing her poor health as the reason. The denial evidently had an effect on the artist who retreated into relative seclusion in the Finnish countryside. Nonetheless, she kept in touch with artists from Paris and kept up to date on some of the most seismic shifts in modern art. After this initial retreat, she produced some of her most raw and radically abstracted paintings that were revolutionarily pioneering. Her work was due to be shown globally, but the outbreak of both wars, led to most exhibitions being cancelled.

Due to her lameness, Schjerfbeck struggled with untreatable pain, which had an effect on how often she could paint. Sometimes she was only able to work for an hour or two a day.

The exhibition offers only around seventy of her works, as most remain in Finland. Despite this, one can witness one of the greatest time lapses of an artist’s life. The changing style of her works are incredibly telling of the internal and external pains and tragedies that became of her life. The self, no matter what subject is on view, is at the forefront of each image.

Her early works were inspired by impressionist painters, such as Manet. However, unlike the impressionists her work suggests a subtle sense of gritty realism and sadness, that are closer to Rothko then Renoir. The Convalescent depicts a young and forlong girl playing with a flower in an empty kitchen, perhaps a portrait of the artist as a young girl, idly waiting for time to pass.

My Mother depicts an intensely phantom like woman at the end of her life, possibly an attempt by Schjerfbeck to understand her mother through the medium of paint. There were overwhelming maternal difficulties between the two and the image reflects this lack of sentimentality. Like most of her later works, the painting is split into flat patches of colour and simplified forms. The subjects gaze is averted away from the painter, a repeating pattern that suggests one has walked in on an air of contemplation. This movement into modernism is where Schjerfbeck is at the height of her talent, and where gallery viewers flock.

As one walks through the exhibition, they will come to a darkened room in which Schjerfbeck examines her physical decline in a collection of grindingly honest self-portraits. The feeling of watching this young woman age, is quite uncomfortable, and evokes the same feeling of being in the presence of someone who is terminally ill. Schjerfbeck wrote to a friend of her choice for self-portraiture: “this way the model is always available, although it isn’t always pleasant to see oneself.” Perhaps her most well-known piece, Self-portrait, Black Background, dominates the room. Painted in the middle of her life, we no longer see the fresh faced girl of previous self-examinations. Instead, a pale woman, with her chin facing up seems to be questioning the viewers fascination with physical decline.

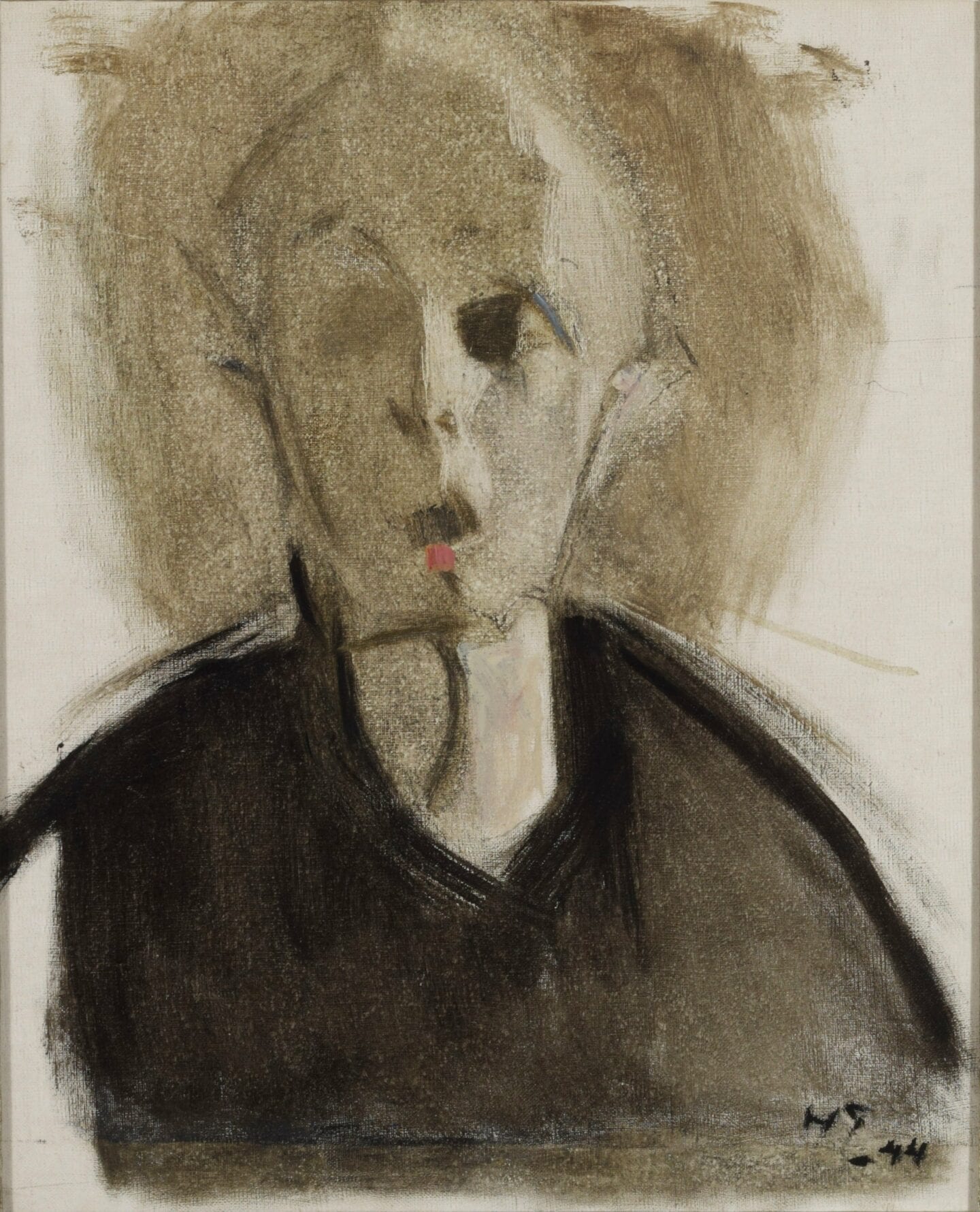

Lastly one comes across Self-portrait with Red Spot, painted in 1944 when Schjerfbeck was 77. Two grey colours, with the suggestion of a face, indicate the end of one’s life. The feeling of an artist coming to terms with her own mortality, and fascinated with the physicality of that change is both comforting and melancholic. The fast and vivid early paintings have slowly dispersed into slow blocks of colour. These later works are evident of a move towards the brutal fascination with the human form that foreshadowed the portraiture of Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach.

An exhibition of her modernist portraits, landscapes and still lifes at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) in London, is finally giving this master of the visual autobiography the credit she deserves. The exhibition is now open running through to October 27th 2019.