The Next Generation of Art Dealers Take Manhattan and Shine Light on New Talent

Trotter&Sholer kicks off their grand opening with a solo exhibition featuring Malaysian artist Azzah Sultan, whose work features traditional Malaysian batik fabrics and textiles. On view until 27 September.

It is time to make way for the next generation of New York gallerists. With businesses perishing and many commercial rent prices at an all time low, three ambitious young art dealers have leased a new gallery on the Lower East Side for the grand opening of Trotter&Sholer, founded by Jenna Ferrey, Angie Phrasavath, and Elisabeth Johs. Their premiere exhibition, Anak Dara features a solo show with Malaysian artist, Azzah Sultan, shining light on an untraditional voice in an industry that is traditionally oversaturated with Western contemporaries.

The term Anak Dara literally translates to virgin, but is used colloquially to mean young unmarried girl. Sultan re-frames the term in a contemporary context as both the Malay word and the English word carry cultural baggage and assumptions, which are compounded for Sultan by elements of religious and cultural otherness. With a father as a diplomat, Sultan has spent most of her life living with her family in several different countries, including Malaysia, Abu Dhabi, Saudi Arabia, Finland, and Bahrain, and on her own in the United States.

The body of work for Anak Dara almost serves as an altarpiece, enshrining the artist’s culture by representing it through visuals, smells, colors, and texture. Through the use of mixed media, Sultan is allowing the viewer to be overwhelmed with various visual signifiers as a tribute to her multicultural background and an investigation of how she perceives herself through painting, fabrics, video installation, and objects of personal memories.

“I saw a piece of her work in a show that my friend curated at the Sotheby’s Institute called Home Sweet Home, made out of headscarves that women sent to her sewed into an American flag,” Ferrey says of the exhibition. “My background is religion and multiculturalism so I really wanted to incorporate her work into our first exhibition.”

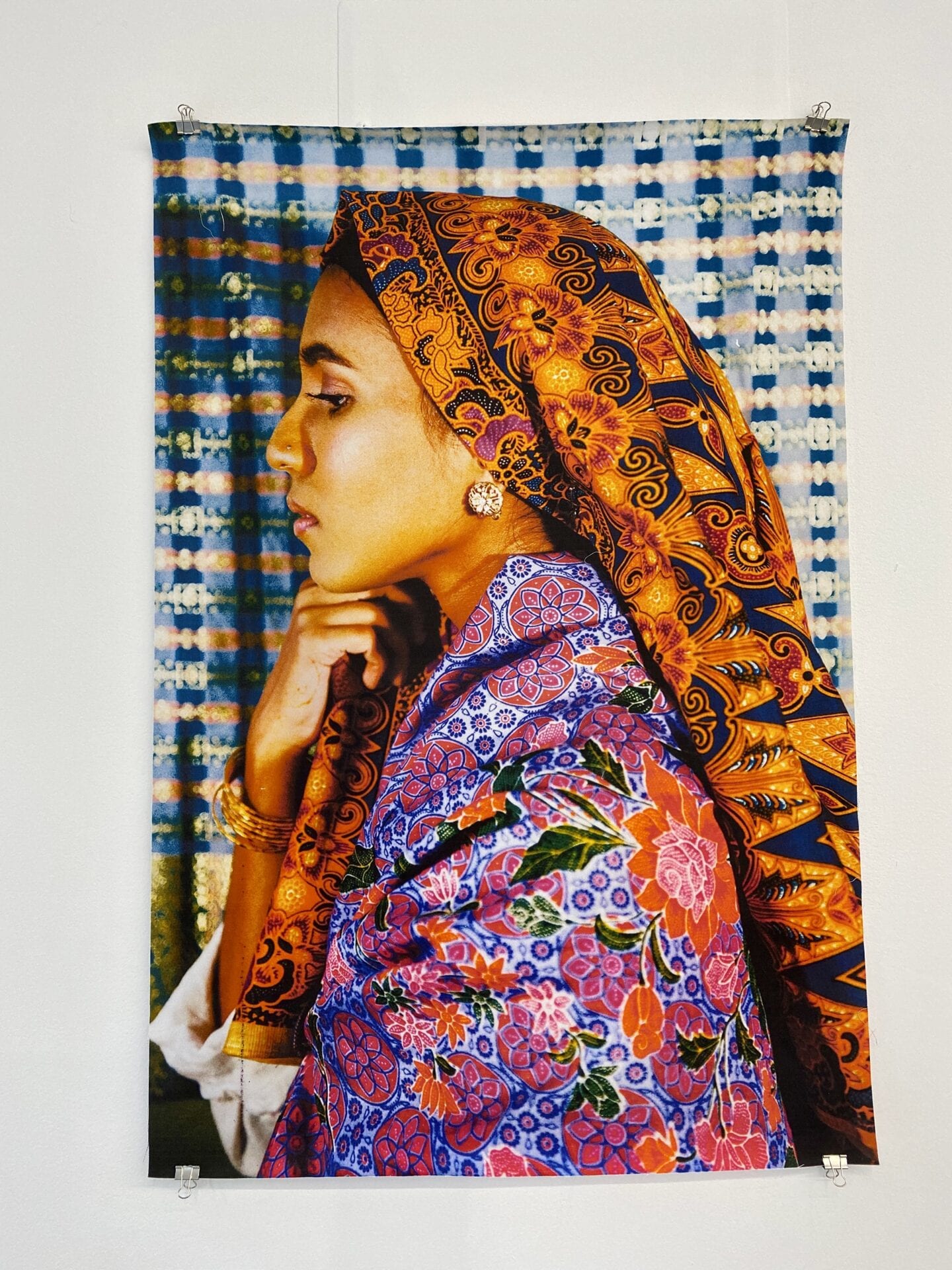

We spoke with the young artist who discusses finding her artistic voice, and reframing her art from the lense of a hijabi Muslim woman to the cultural threads that are woven throughout her life with the use of traditional Malaysian batik fabrics and textiles.

Tell us about this current exhibition.

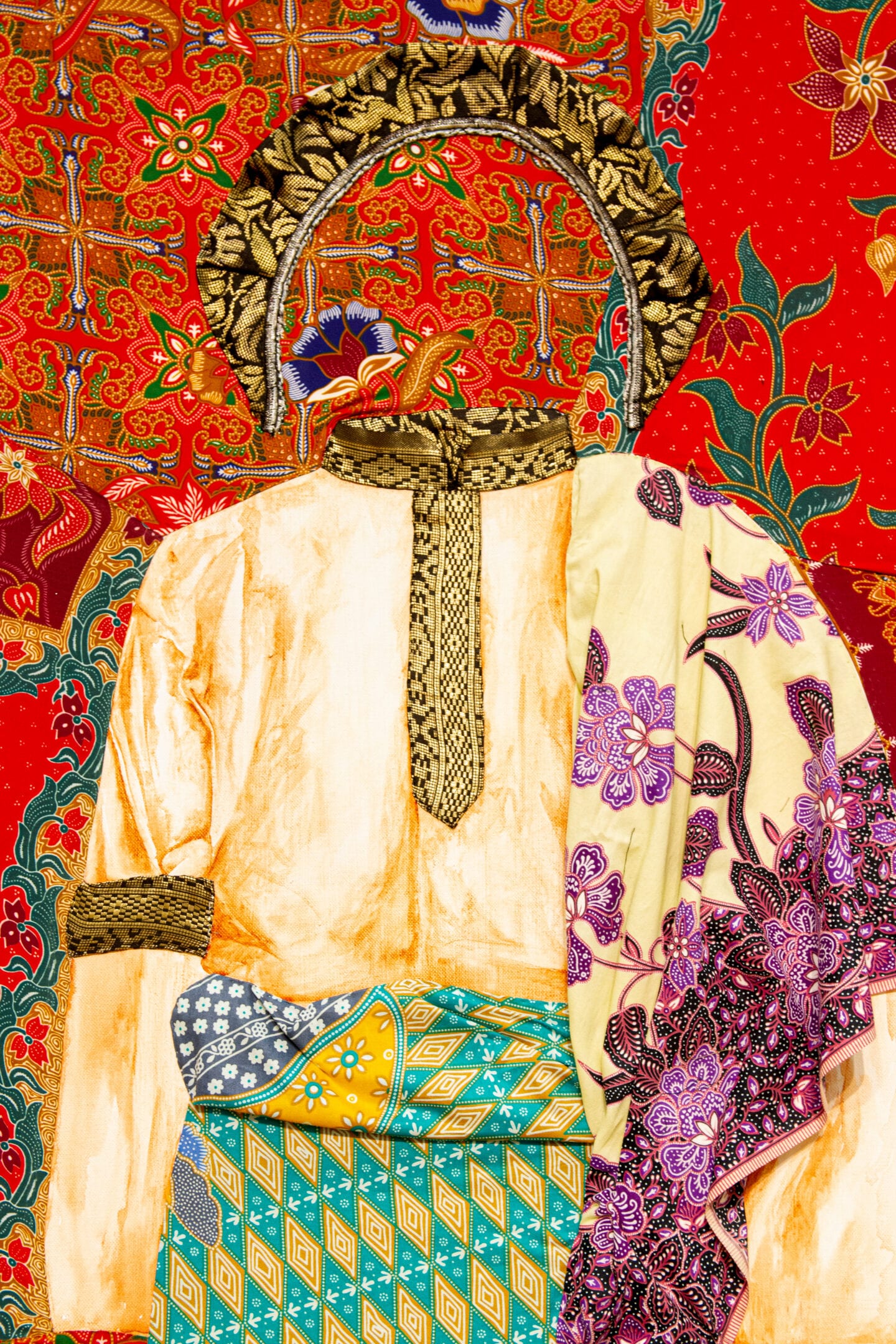

I use art as a way to represent my own Malaysian identity. Our culture, traditions, and customs are all intertwined as representations of our dignity, legacy, and family upbringings. For my art, I am interested in exploring my identity through the materiality of batik prints, my relationship with my mother, and objects of nostalgia. A piece that investigates my background is Anak Mami, an exploration of my cultural identity, looking at my Malaysian background and how it relates to my Malay, Indian and Pakistani bloodline.

The word “Mamak” is a term referring to the Indian Muslims who migrated from mostly South India to Malaysia, landing in Penang as the first port around the twelfth to the eighteenth century. They settled down in different working activities and businesses of which food was the main industry. Indian Muslims played a fundamental role in Malaysia from global trade, introducing Islam and building mosques. The garments incorporated in this work are pieces borrowed from my mother and father. The jewelry of Indian and Malay mix was borrowed from my mother. This mixing of patterns has brought light to my relationship with the cultures I grew up with. Malaysia is a diverse community mix made up of Malays, Indians, and Chinese races that the intersectionality of these races is what makes up the Malaysian rich cultural community. Nonetheless, coming from a mixed background you are often categorized as one or the other.

How did you know you wanted to be an artist?

For me growing up, art was always the one constant source of stability for me because I moved around a lot. It was always a way for me to keep developing and express myself. I was always fascinated with how people were able to express very important issues through a visual and audio presentation, I realized a lot of my school work would always take the route of a creative step, when I turned 15 I started to believe that this is something that I could do for real, which was when I applied to art school.

How does your religion and multi-cultural identity influence your work?

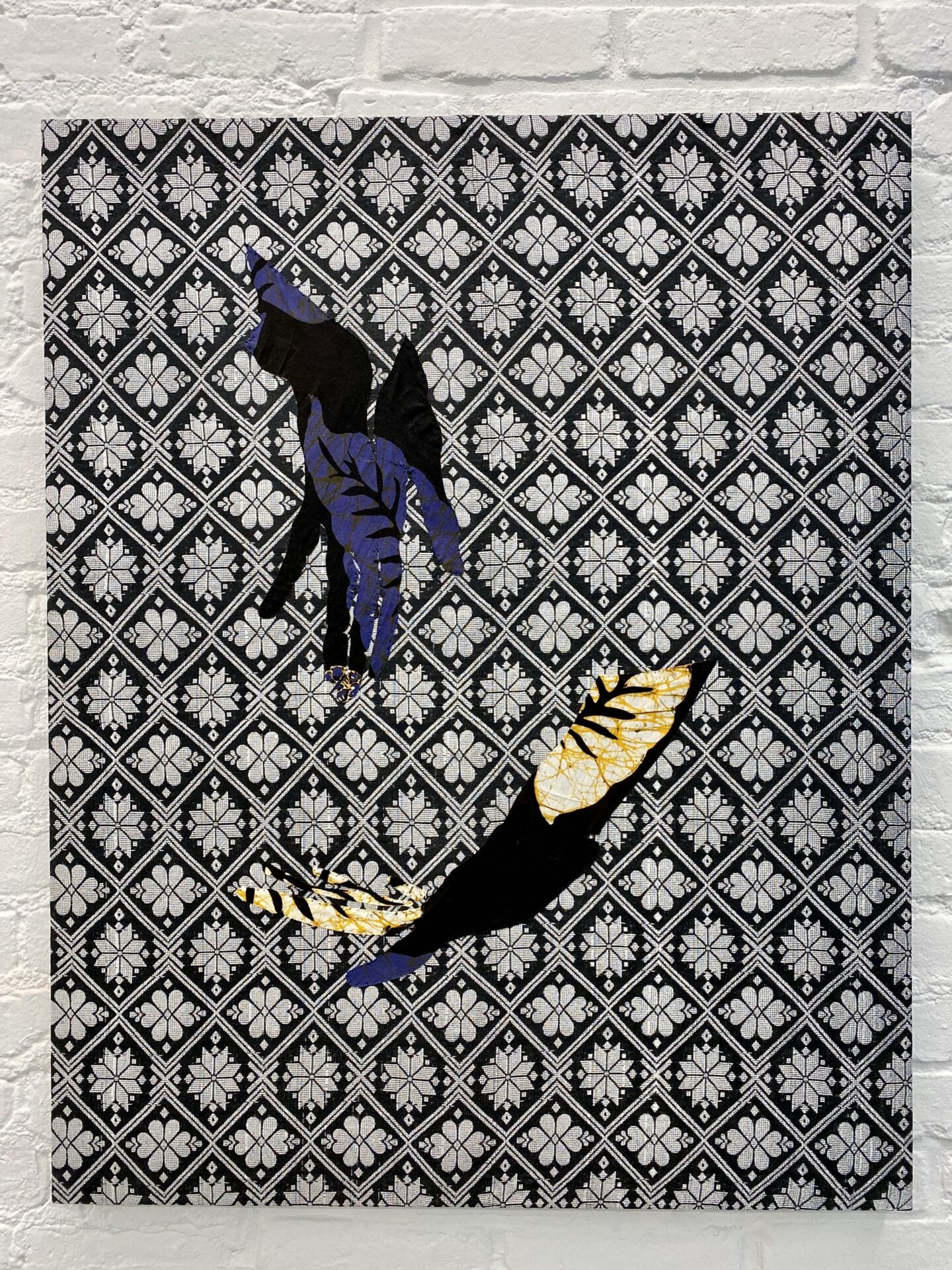

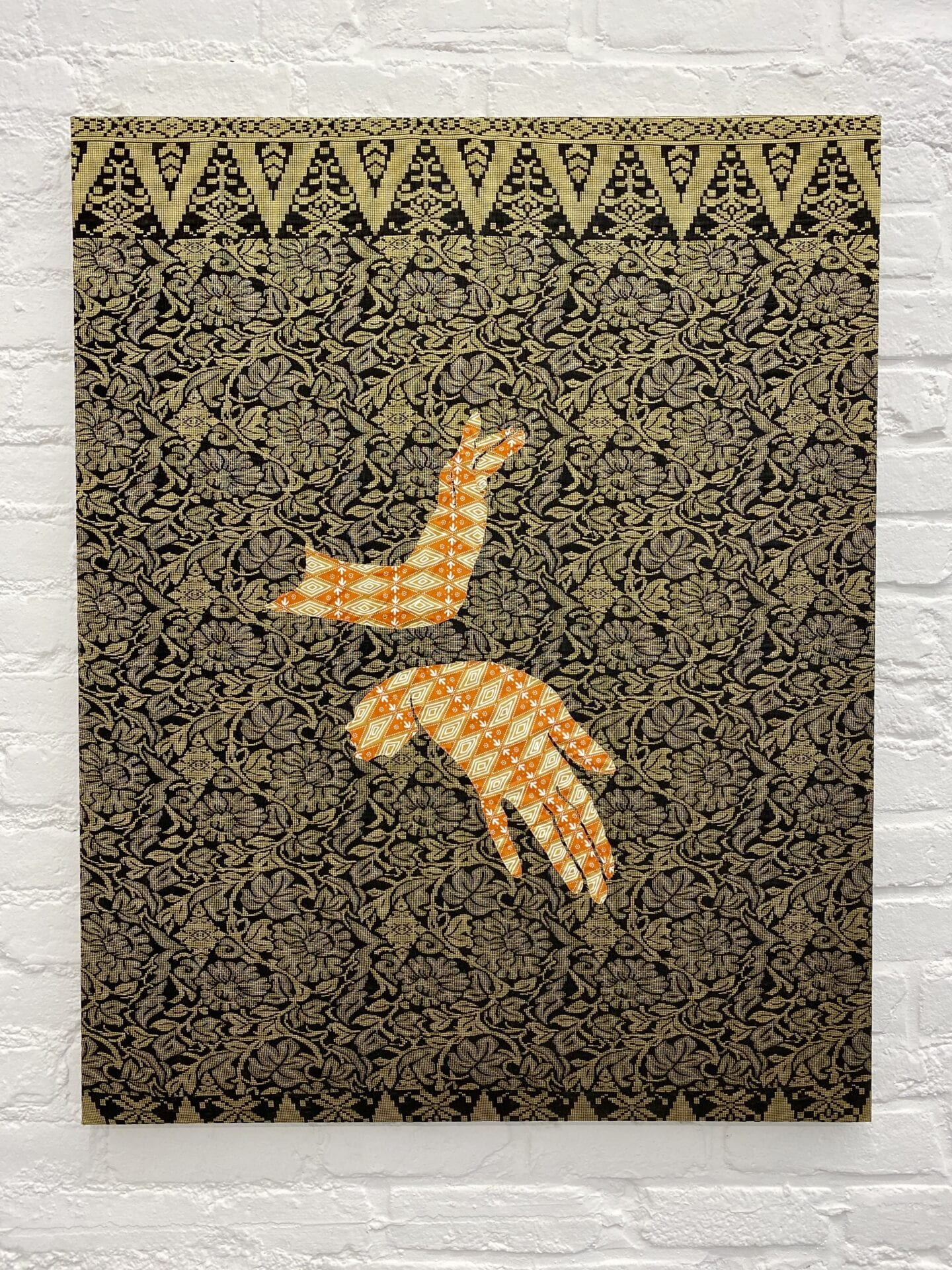

Growing up in Malaysia, our culture and customs are all very important areas of familial focus. It is important to not lose touch of who we are; the rite of passage to transfer knowledge which is traditional to pass on from one generation to another. For me, religion and culture is a fundamental point of my identity, as I am physically seen as Muslim with my hijab. But within my art I try to display those parts of my identity in a more nuanced way, where it doesn’t just symbolize the entirety of who I am but it is just a part of me. There is still so much more to me, and this the use of the lack of body within the Anak Dara series of work. The lack of the body is resolved through fabrics draping of the form or layering of videos to create ghost-like outlines of the body, the only representation of a human form we can see is through my mother’s hands as well as my own that is reflected in several performances for the Anak Dara show. The term “Anak Dara” is a Malay term that translates to a young and unmarried child. It’s a term of endearment my mother often uses. Here “Anak Dara” is an ode to the diaspora of leaving home and the journey of recovering what was lost through materiality, performance, and the power of my mother’s voice.

Where do you source the fabric in your work and what inspired these in your pieces?

A lot of the fabrics and materials I have used in my body of work come from my hometown in Penang, Malaysia. I was able to find fabrics, spices and objects of nostalgia simply by exploring my hometown with my parents and having them a part of the process of collecting these materials. A word that has stuck with me whilst exploring my thesis idea is Adawx, a Tsimshian native term to illustrate the oral history, recording, recollections of traditional practices and storytelling.

Through the use of translating my mother’s instructions on how to make sambal, a Malaysian chili paste dish, I am translating an oral history through performance art in my piece Memasak, meaning “to cook.” Preservation of traditions is very important to not forget your past, I am preserving my memories of my mother through these actions and using food as a personal fabrication. By wearing clothes in my mother’s fashion style, using batik fabric and Malaysian patterns, these objects empower my identity and engage with the viewer to intensify and create a cultural environment through the video.

The sambal dish is a very basic and staple part of any Malaysian cuisine, it enhances the flavor of the food and opens up your appetite. This performance piece is part chronicle and part remembrance, the action of my mother cutting these ingredients and incorporating them into a dish holds healing qualities for me. The image of my mother cooking in the kitchen is a very prominent one, it not only stimulates aromas that I can recollect but also traces back to the actions and events that occur surrounding the food being prepared. The gaze is important within my work, for the piece Memasak there is a huge lack of it. As a viewer, you can’t see my face and you’re unaware of where my gaze is, my mother is only be represented through her hands which creates a mirror dialogue to my hands that are being shown. There is a disruption of who is being represented within this piece and our only evidence is the colors, fabrics, jewelry, and voice that is being shown and heard.

You talked about growing up Malaysian dancing and having a performance where you wore traditional male garments. Explain the themes in your work involving gender.

The art piece Melipat hints towards the human form without actually representing its physical attributes but using clothes to fabricate the body. Each mixed media display of a figure is based from images of myself when I was young and used to perform Malaysian dancing which was taught by my mother and a way for her to expose my sister and me to our culture as we were constantly traveling and living in places outside of our home country.

There is a personal tie to the way the figure is displayed, these first started off as paintings but I decided to take it out of the two-dimensional realm and include textiles to display the body as if it was coming out of the canvas. Each canvas has an acrylic painting of garments and or a veil that drapes over to convey. the presence of a body. I cut, stitch, and fold the batik fabric to produce specific traditional Malay clothing, this is hand-stitched onto the canvas and creates a great contrast against the burnt sienna acrylic painting.

The theme of gender in my work is a little being skewed as I am adopting the fabrics to develop the body, the only hint towards my femininity is seen through my hijab, and even that is challenged in a way through the piece Melipat. One of the garments embodies an outfit that’s mainly worn by men, a baju melayu with a sampin, this was an outfit my mother chose for me to wear when I performed a Malaysian dance as a child because I was taking on a more male role within the performance itself. I like to blur the lines between what is seen as traditional roles of gender. I also am interested in the matriarchal role of how oral history is passed down from mother to child.

You told us that you began wearing the hijab before moving to the US. Explain what inspired this.

I felt like I needed something to remind me of who I am and where I am from. I always have an interesting relationship with the hijab, there are days where I feel super empowered wearing it and there are days where I question myself. But I believe that’s the very nature of the hijab, its to be able to see more of myself and not based on my physical attributes, but rather who I am through my actions and my responses to my environments. I do believe though my art is always seen as political because I wear the hijab, and although that is a lot of pressure, for me it illustrates the way society tends to treat people who don’t fit the cis and white normative box.

You mentioned that a professor once said your work could make people uncomfortable. What was your reaction to this?

The first time I heard that I was a bit taken aback but I think from then on I felt like I had to keep making work that challenged my audience. People have a perception of what I am, that I am shy, naive, and softspoken so they tend to get confused when my art is very direct. The experience taught me to not let others influence my work if it’s coming from a place of xenophobia.

You tell us how you are over the idea of being a trope within a lot of shows and that a lot of your old work focused on Islamophobia. Tell us how your work has changed within the last 7 years of your career.

There are times where it is very obvious people want to include me in shows because I fulfill their diversity quota, it does get quite tiring because they tend to not see my work for how it is but rather as a tool to show how diverse their exhibition is. For a while, I did create work that talked about what it is like living in America and dealing with Islamophobia, but after a while, it felt like that work was more pleasing to others than it was to me. So when I started making it a little be more outspoken and unapologetic, people saw it as too aggressive. There is this narrative, every time artists of color create works of art that are very to the point and confrontational it is seen as aggressive. The reason being, people are afraid to deal with their biases. Which is why it’s so important to point it out in art, once you understand your biases, then dialogue is created, slowly you start to not be ignorant towards it. After a while, I felt the need to shift my work more towards my cultural identity because that was something I always struggle with and wanted to explore more.

Lastly, who are some women artists that inspire you?

So many to chose from! But here are my biggest inspirations: Emily Jacir, Lorna Simpson, Mrinalini Mukherjee, Carrie Mae Weems, Baseera Khan, Bouchra Khalili, Meriem Bennani, Arshia Fatima Haq, and Tschabalala Self.