Saving Trees Through Art: Nikolina Kovalenko

Russian artist Nikolina Kovalenko’s latest project, Saving Trees Through Art, provides support for those rebuilding the Amazon rainforest. For each of her diptychs sold, collectors send part of the profits to local Brazilian projects striving to decrease and reverse deforestation.

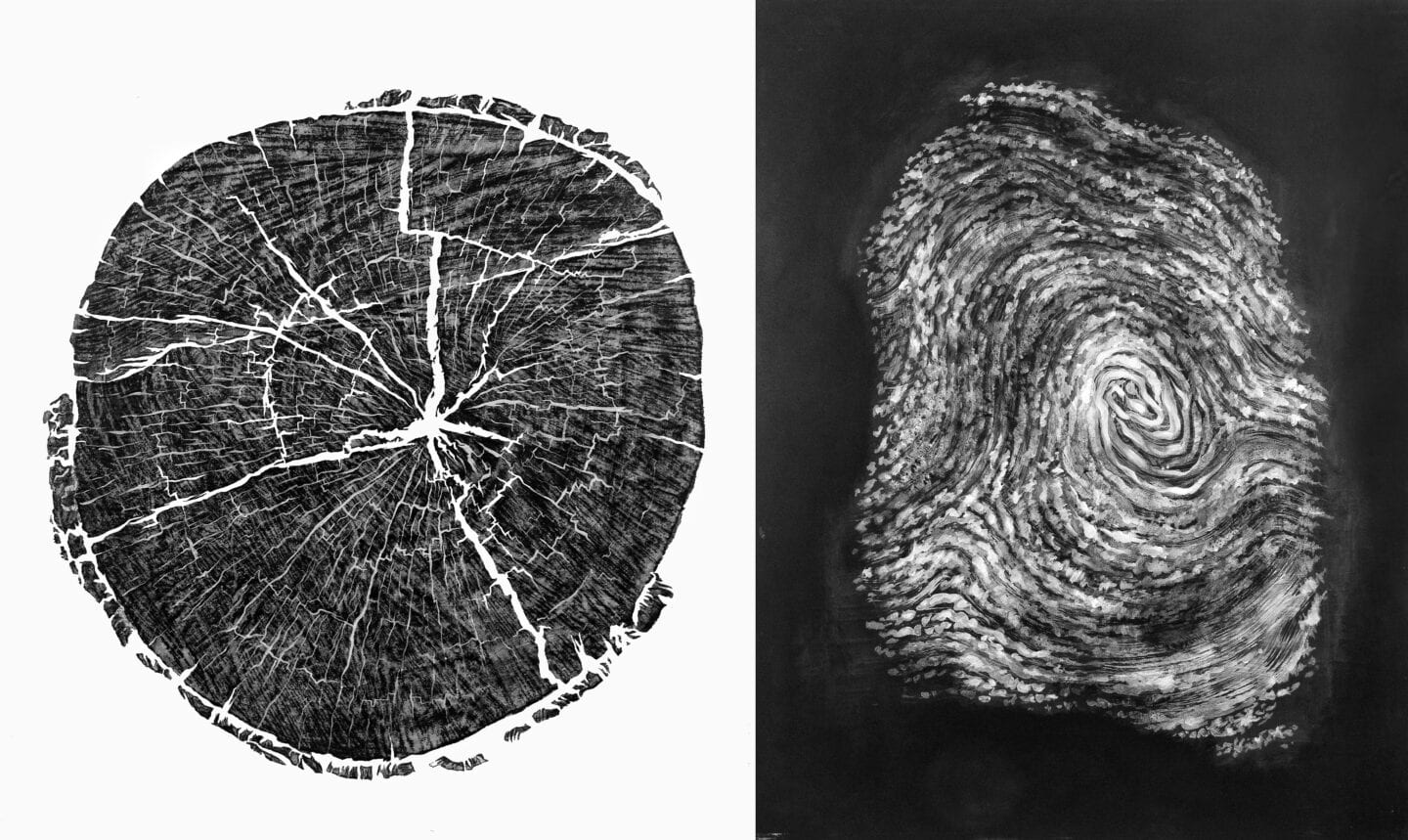

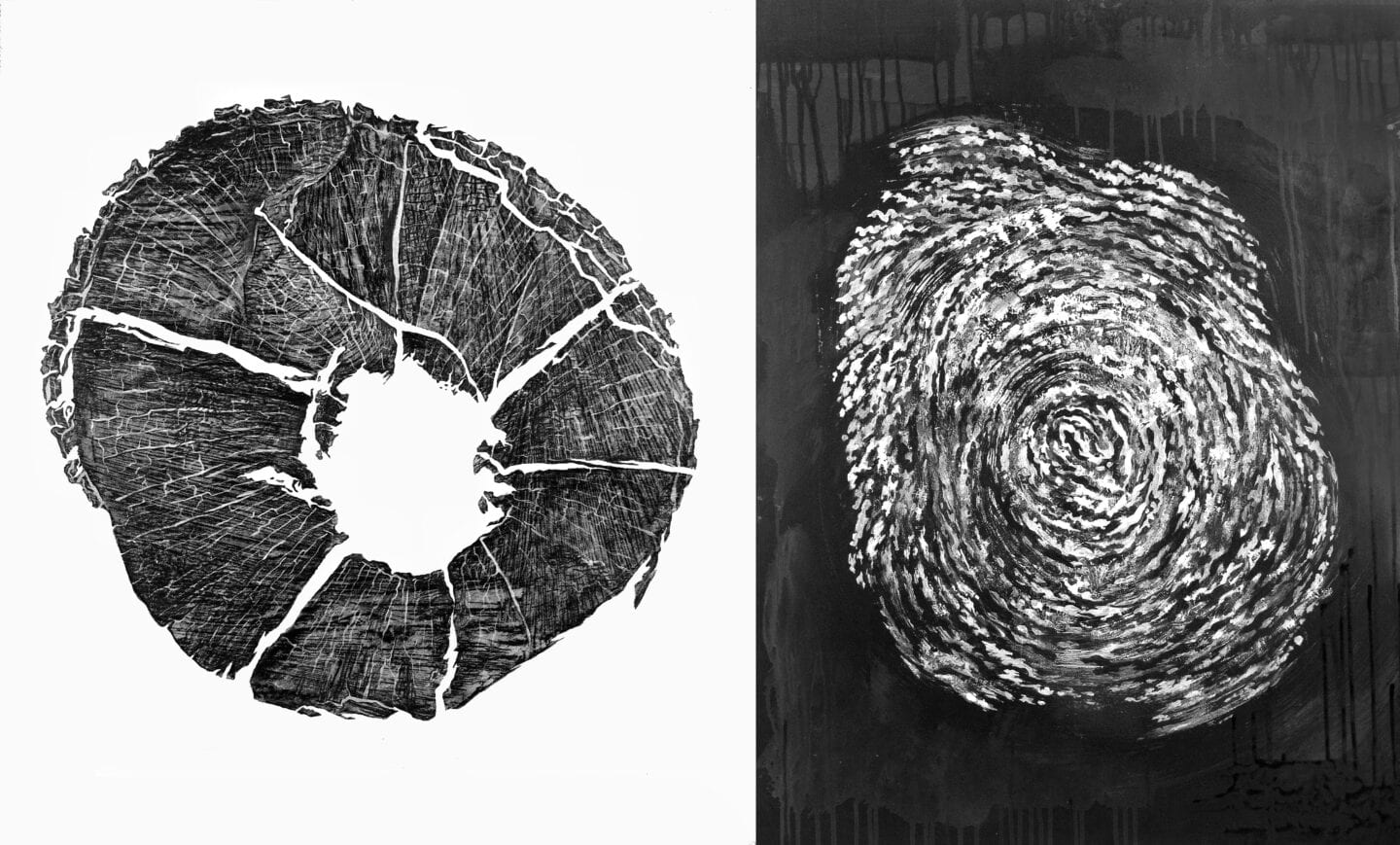

“I feel like every tree, mountain, and river has a soul,” says Nikolina Kovalenko, a Russian artist based in New York City whose work explores humanities vanishing connection with nature. Her most recent project Saving Trees Through Art, explores the symbolism of texture found in nature. The diptychs pair the rubbings with graphite of the remains of logged trees in the Amazon Rainforest in Brazil, with a fingerprint of an NGO or independent activists who is committed to the restoration of the rainforest. Each diptych acts as a portrait of the fallen trees, preserving them, like the activists, with a “fingerprint” of the tree rings.

Kovalenko’s work in the Amazon took her to remote parts of the world’s largest rainforest. Taking advice from local guides, she found herself at logging sites thanks to generous hosts. Kovalenko traveled via bus, car and even motorcycle, to get to the border between Brazil, Venezuela, and Guyan, where she found the sites to conduct her rubbings of the trees and meet NGOs.

The destruction in the Amazon, as Kovalenko explained, began with the Brazilian government’s creation of the Trans-Amazonian Highway that created settlements in the heart of the Amazon. These empty acres of land were advertised with the promise of 250-acre plots, six months’ salary, and easy access to agricultural loans, in exchange for converting the surrounding rainforest into agricultural land. The hope was that these settling families would produce crops such as beans, maize, cocoa, coffee, and other crops to supply the domestic market. However, the soil in the Amazon basin consists mostly of sediments, which when subject to the Amazon’s heavy rains, flooded the roads leaving the settlers cut off from their crop for six months out of the year, leading to dismal harvests. In 1974, the project was finally abandoned but about 20,000 families remained in the region, many of whom were left in abject misery by the Brazilian government.

As Kovalenko explains, “The toughest thing about logging (and any other environmental issues in the Amazon) is that no one is really a villain, most of these people are just struggling to provide for their families. In my opinion, it’s more government’s fault for failing to provide sufficient funding and government-run farming programs where guidance on sustainable farming would be offered.”

How did the project come about? And what drew you to the Amazon Rainforest?

My work is about humanity’s fragile connection with nature. The Amazon Rainforest is a place where it is overwhelmingly powerful and human presence is insignificant, restoring the balance long lost in other parts of the planet. It all started when I did a drawing of a tree trunk. I thought it looked like a fingerprint—indeed, a tree’s age rings, and other marks drawn from its life experiences are just as unique as human fingerprints. I wanted to find a visually concise way to convey this idea. After several weeks of researching and brainstorming, the project came together. I view these diptychs as yin and yang, recreation balancing out distraction. I needed funds to proceed, so I started a Kickstarter campaign to cover basic travel and art materials and was amazed by the excitement and support I felt from friends and strangers alike.

What has it been like working with loggers and gathering the “fingerprints” of trees? What have been some of the challenges?

The most obvious challenge was finding the actual sites–as you can imagine they are not exactly advertised. Not to mention the danger—even police stay away and prefer not to get in trouble. As an outsider, it was extremely difficult for me to find out this kind of information.

The scale of the devastation and the size of the trees surprised me, and even though Paola explained to his coworkers that I’m collecting material for my art project, they were very suspicious of me as they thought I might be a journalist. I spent 2 days under the baking equatorial sun taking frottage from the logged trees by placing a paper on the cut and rubbing over it with graphite… I couldn’t help but thinking how unique each pattern was, and how majestic and grand these trees once were.

What have been some of the challenges in creating the work and also working as a woman in Brazil and in the art field?

Situations I got myself into while traveling and working on my projects are not safe for anyone, especially a women, and I’m very lucky and grateful that nothing bad happened to me. As a woman you’re more vulnerable, not because of nature and wilderness, but because of people you can meet in those isolated areas. I wouldn’t feel comfortable camping in the jungle by myself for example (however it did happen once out of necessity). In a way it limits how far off the beaten track I can go by myself, without a male companion I can trust. As for the art world, several times I found myself in a situation when I am thinking we’re having business meeting talking about my art, and a gallery owner/curator/collector is trying to turn it into a date. It really infuriates me that I wouldn’t have to waste my time on these “meetings” if I was a guy.

How have you worked with NGOs and other volunteer groups in restoring the rainforest?

I met with a variety of environmental activists, and I learned so much from them. Each person I interviewed works tirelessly (and often without any compensation) on saving the rainforest. From volunteers planting trees, families buying land from the government and creating natural preserves to save the primary forest, professors teaching forest engineering and management, sustainable farmers, to scientists who study the genetics of the local seeds to ensure the healthy and rapid growth of the secondary (replanted) forest and big organizations like Idesam whose mission is to promote sustainable use of natural resources and to find alternative solutions to environmental conservation, social development and climate change mitigation. Along with the volunteers’ fingerprints, I asked them to write a couple of sentences about why they care for nature and what motivates them to act. On top of that, I did the actual reforestation work replanting the secondary forest.

What has been the reaction to your diptychs? How do you hope Saving Trees Through Art will be received and help with the prevention of further deforestation in the Amazon?

The reaction has been overwhelmingly positive, and I feel like this project really shed the light on the environmental issues in the Amazon. People care, they are just not always aware or have all the information. Apart from the conceptual part, I would like to think that the diptychs work as abstract fine art objects on their own. Art is such a powerful tool to make us see things from a new perspective, and I believe that visual images sink in better than just information and facts.

I think knowledge is everything, if this project can do as much as make people think about how we’re treating nature, if everyone plans at least one tree in their lifetime, stops or at least reduces their consumption of beef, be diligent about recycling and better even take their own bag to a grocery store, or make a small donation to an organization focusing on saving natural resources or animals. It’s easy to think that your action will be just a drop in the ocean and won’t really make a difference, but together we can, so just focus on how you can help. No action is too small.

With climate change rapidly reshaping our world, what does making art responding to it mean to you? Why do you feel it’s important?

Apart from rainforests and deforestation, my art also explores glaciers melting, coral bleaching, the interconnectedness between elements, fleeting experiences and time. I like finding different new ways to connect with the world around us and to integrate into it without the feeling of superiority. So far we’re the most invasive species on earth, and I like dissolving into nature and becoming one with it. Nature gives me energy and inspiration, the only thing I need to do is to convey it on my canvas so that feeling is never lost.

Featured image – Photo courtesy of Marina Tychinina.

Nikolina received her MFA from Moscow Surikov Art Institute in Moscow, Russia in 2011 and studied at Universität der Künste in Berlin in 2010 and holds a Gold Medal from the Russian Art Academy.