Paula Crown: Wielding Art in the Fight for Justice

From Wall Street to the art world: Aspen artist and Chair of MoMA’s Committee on Education is donating proceeds from her multimedia works to the Art For Justice Fund in support of reforming the criminal justice system.

In the interconnected world we’re used to that has many of us currently isolated, it’s easy to feel that our contributions to society have dwindled. However, in collaboration with the Art For Justice Fund, multimedia artist Paula Crown is advancing the cause against mass incarceration by doing what she does best: creating art.

In the last decade, Crown established a successful atelier (studio), was appointed to President Obama’s Committee on Arts and the Humanities, and currently serves as a member of the board of trustees at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, chairing the Education Committee. The most iconic and recognizable body of work is her large-scale sculpture, JOKESTER, which takes Crown’s solo cup sculptures and brings it to a monumental scale, serving as a reminder of consumption, waste, pollution, and re-use, currently on view at Sculpture Milwaukee Biennale. Formerly installed in Aspen and in Miami’s Design District, the work embodies Crown’s commitment to tying her artistic practice to concrete social change – (in this case) the mounting climate crisis. The signature 10-foot red sculpture acts as a stop sign, encouraging individuals to pause and examine how we shape our world, how our world shapes us, and the marks we leave behind in transient moments.

Coinciding with the growing global call to radically examine our reliance on single-use plastics, in the past few years this series has become a visual symbol of recent campaigns by consumers to push businesses to use more sustainable products. Plastic straws have been removed from many establishments and the company Ball has recently introduced an aluminum version of the famous cup responding to consumer concern over the environmental impact of the standard single-use, disposable cup. Programs with various organizations have created community engagement around the sculpture, including a collaboration with the Surfrider Foundation to clean up one pound of plastic waste from Miami beaches for every photo shared on Instagram during Art Basel Miami Beach 2018.

“Single-use plastics and our insatiable appetite for natural resources continue to threaten our environment, and, frankly, our existence,” says the artist. Crown asks: “What happens to all the plastic we use only once and toss? Who cleans it up? What are the permanent traces we leave behind?” drawing attention to our position as complicit consumers who have the power to change our legacy.

With a practice encompassing drawing, painting, video, and sculpture, Crown rigorously incorporates cutting-edge technology, social activism, collaboration, and a commitment to sustainability in her studio practice. Crown’s works are in numerous public and top-100 private collections including the collection of Agnes Gund, the founder of the Art For Justice Fund herself. The “de-carceration” fund promotes justice reinvestment by bring together a community of artists, advocates, and donors to address the brokenness of mass incarceration and reform our criminal justice system, aiming to disrupt the very processes and policies that lead to high prison populations.

“Art has the ability to provide a respite from these turbulent times,” Crown says. “There is growing fatigue over the polemics in politics, religion, and culture. There is undeniable power in empathetic connection. Our future will be shaped by those who adapt, pivot, and collaborate creatively.”

A prolific artist with no shortage of her ideas and inspiration, Crown speaks to us about her passion for making a mark in the world through powerful expression. For a limited time, all profits from Crown’s selected works will go toward the Art For Justice Fund.

You began your official career as an artist after years on Wall Street and a family business but have been creating from a young age. What made you decide to make the switch and pursue art as a career?

There was no choice. My creative self had to be more fully realized. Since childhood, I intuited that ideas could be conveyed through visual language and mark making. For 25 years, my life was beautifully chaotic with 4 active children and my husband, extended family, and board engagement in both the not-for-profit and profit sectors. But as the children grew, my needs evolved and certain “shoulds” and obligations lost relevance. It was an open moment.

One day while multitasking, sub-optimally of course, (I was likely drying my hair, listening to the weather forecast, and preparing for a meeting) I just suddenly stopped. I grabbed a pen and wrote the words, I AM AN ….ARTIST. That act alone focused my attention and provided clarity around the necessary steps needed to pursue a serious career.

“Periods of such concentrated attention granted me the grace of courage. Not in a heroic sense, but in a generous and intentional way. (The derivation of courage is from the French word “Coeur“ meaning heart). An inner spaciousness gave rise to important questions as to the essential and worthwhile in life. How could I be more truth-seeking and less approval seeking? And, how might my abilities be useful to the world?”

What do you think made you pause at that very instance?

It is hard to say, but my hunch is that my mediation practice and a deepening awareness of my own thoughts and emotions played a role. Over time, I realized that I was not fully expressing my creative possibilities. I became increasingly attuned to my senses. Paying attention to these direct experiences provided grounding and reflection. My lifelong fascination with navigation and spatial cognition now made sense. There is an undeniable potency in being fully present; it allows for the emergence of an interior intelligence about the invisible: the connections among the physical, mind space, and a larger consciousness.

“I became a black belt in saying no, which frankly is never easy.”

What was the reaction of your friends and family when you decided to become an artist?

People frequently ask me two questions: How did I do it and why? One family member asked if I was going to become a professional house painter. Others said they were pleased to know about my new hobby. I intentionally sought out wise voices, and let’s just say that my noise-canceling headphones served me well during this time. Truth be told, moving towards a creative identity was not difficult. I intuited a navigational pull and visualized possibilities. There was a clarity and calm confidence within me. Of course, there were numerous pragmatic issues to manage in the periphery. Vigilance against distraction was on red alert. With discipline, I cleared my schedule and discontinued board service, with the exception of MoMA and President Obama’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities. These were informative to my burgeoning practice. But otherwise, I became a black belt in saying no, which frankly is never easy.

What was the next step you took towards your creative career?

I assembled a portfolio and applied to a graduate program in painting and drawing at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago. I smiled broadly and breathed deeply when I received an acceptance. It just felt right. My professors there, the majority of whom were women, reinforced my confidence that my artistic voice was valid and that it would be useful in the world. Their assurances assuaged the continual wave of guilt I experienced about the work I left behind and the emails that went unanswered. I knew I had to become monk-like as a way to get to the deep work of studio practice. By and large, it was a time to expand my skill set and to follow my curiosity. More detailed stories about the adventures of a 50-something at art school will be saved for another time. In 2012, I graduated with a Masters in Fine Art and I opened my studio in downtown Chicago in 2014.

“When people ask me how to find their passion, I tell them to remember what they loved as a child. There seems to be real wisdom there.”

How is your art different now from when you first began? How has it been informed by your life and experiences?

This is such an interesting question and upon reflection, it hasn’t changed much since childhood. I no longer etch my father’s albums with the record needle, nor do I draw on people’s wallpaper or ceiling car fabrics (without their invitation). I also have moved away from building towers and cities with bricks represented by heavy encyclopedias. That being said, there is knowledge in what we are drawn to before we are aware anyone is looking. When people ask me how to find their passion, I tell them to remember what they loved as a child. There seems to be real wisdom there.

I have always been a mark maker. Most typically in two-dimensional realms such as drawing and painting. While in graduate school, my knowledge expanded and extended to video, installations, and sculpture. Drawing was key in enhancing understanding and expanding ways of communication. It is a mode of thinking and processing information that activates optical senses through the brain and hand. To this day, this is my starting point using a graphite pencil or a digital pen. An evolving practice includes myriad tools and I get pretty excited thinking about new ways of creating. There is no imposed hierarchy of one material over another—I consider how a mark or material can evoke an experience and express an idea.

My work is frequently layered. Paint, encaustic, and images combine in a rich conversation. I also have an enduring obsession with tape; colored, flexible, metallic, new off the roll, or previously used. It inexplicably finds its way into a lot of my work. This layering reflects our lives—palimpsests of memories, sensory input, and responses. Our brains and bodies contain a wondrous database of lived experience. The surfaces of my work then become receptacles of our own unique stories. This approach reflects a personal interest in new perspectives and what revelations they may provide. Distorting, inverting, or dimensionalizing work challenges my perception. Something that I thought I understood, becomes unfamiliar. I am standing in the same place yet everything is different.

Tell us about your plastic red cup series. How was this inspired?

Over time I have paid closer attention to what interests me. I more fully trust myself that a particular thread of inquiry will lead me on a worthwhile journey regardless of the outcome. I believe that the road to many successes includes many failures. In many cases, something that I thought I understood, becomes unfamiliar. My SOLO TOGETHER series started in this exact way – by noticing how people interacted with a red plastic cup. These cups have assumed an iconic status of single-use convenience and American college drinking culture. But its use goes well beyond campus life, as evidenced by its prevalence everywhere we go: on our streets, oceans, and in our landfills.

I began to observe each individual form, no longer solely as leftover garbage, but as a representation of its previous holder. We constantly make unconscious gestures and vibrations in the world, and I noticed how holders often expended energy to alter their cup in some way. Cups were twisted, crushed, or split apart and assumed new forms. These marks become reflections and documentation of the person who has left it behind.

I went on to crush 300 separate cups, made plaster casts of each, and painted them in detail. The plaster cups are weighty, as I imagine that they have become recipients of the holder’s energy. A name for each cup was imagined and applied, bestowing personalities to each individual cup, reflecting cultural concerns of being insta worthy, never good as dad, failing out, and jokester. When exhibited on the floor the cups collectively became something else…a zombie space of prior gestures and memory.

My primary motivation in undertaking this project was to highlight and show respect for the way each of us exists uniquely in the world. It soon provoked further questions as to who exactly is responsible for cleaning up all of these cups and the deluge of non-degradable single-use plastic products that are destroying our natural environment. It is clear to me that solo and together we can find the right balance between convenience and disposal.

My investigative thread continued on by later altering the scale of the cup to a monumental size. I selected a cup called Jokester because of how it sat on the ground and because its form had the potential to become a topography of sorts. After considering specifics around size, material, and engineering I felt Jokester on a grand scale could transcend its original meaning beyond being a large sculptural cup. It became something much more, the vibrant red color went beyond the cue of a party, it represented an alarm and a visual stop sign to consider. It is in your space and it requires negotiation around it. It is engaging and poses meta-questions of how individual actions affect each other locally and globally. The current pandemic underscores our interrelationship with our environment and with others. Your mark matters.

Has there ever been a moment where your experience changes your interpretation of a work you’ve already created?

Yes, in 2016, I debuted a solo exhibition Bearings Down at the Goss-Michael Foundation in Dallas. The show was an aesthetically striking and visually charged immersive installation, with the work of the same name at the center of it. The exhibition was about bringing forth a comprehension of one’s position in this uncertain dynamic world.

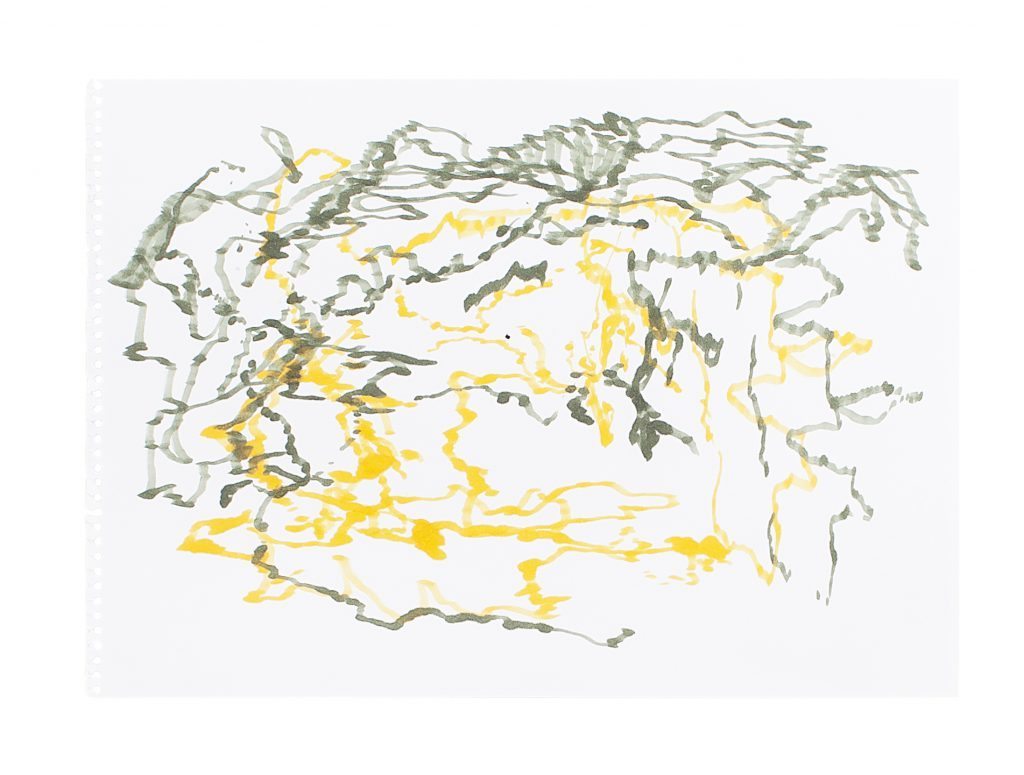

It is fascinating to observe how one idea can lead to another. I see this as a characteristic of many artists; objects and spaces hold transformational possibilities. Bearings Down was initially derived from my original Africa Drawings (2010). These were sketches made while flying in a helicopter above the Drakensberg Mountains of South Africa. They were a record of the experience of changing directions, turbulence, and multiple points of view. Given their ethereal starting point, I worked with Adam Lowe and his brilliant team at Factum Arte in Madrid to dimensionalize the drawings (they were in fact depth maps) and etch them onto glass. A mirrored box was fabricated to further enhance reflection and illusionistic space.

However, during shipment, the work was damaged and the glass partially broken. It was maddening and saddening at the same time. Not one to be wasteful, I thought of ways to repair and redefine it. What could be created from the glass shards? The Japanese art of Kintsugi provided inspiration. I liked the idea that strength can be found in the broken parts. Ultimately I turned away from repair and focused on further destruction of the surface, testing various methods with hammers and glass cutters. I arrived at the idea of using silver ball bearings to break the work. I loved their weightiness and round form. This tied nicely back to navigating space and locating our bearings.

I was mindful of the act of throwing the balls at the glass surface and the resulting effect. The creative gesture started there. The repeated assaults were captured with high-resolution audio and video. The video work was shown on custom-designed screens, which debuted at the Goss Michael Foundation in Dallas with the sculptural work at the center. This version incorporated the sounds of shattering and tracked the paths of the rolling ball bearings. Image, video, and sound coalesced to create a micro and macro landscape. This experience and resulting art illustrate how unintended events catalyze future opportunities to create. The reverse side always has a reverse side.

“Take action. Even if you are afraid and your voice shakes.”

As a multi-media artist, how would you encourage new and aspiring artists to experiment with new styles, technologies, and media?

It starts with noticing what interests you. That is more likely to hold your attention. Then think about the ideas and concepts that you want to explore. Art is a language and artists make ideas present. Follow your curiosity, embracing the fact that your path is unique. Take action. Even if you are afraid and your voice shakes.

Hard disciplined work needs to be undertaken. No one is exempt and ideas can often emerge from the process. Immerse in the canon of art history, critically consider the sources and be aware of its gifts and its limitations. Go to exhibitions, concerts, dance performances, and be aware of what truly draws you into deeper concentration. Feel what you feel.

Take action. Unlike plant life, we were designed to move. Sharpen your skills and tools of communication. Read, journal, and learn about the workings of your own mind. Convene with those who you trust with your most vulnerable instincts. They will inform and reinforce your path. Accept the inevitability of failure along the way. View it as clear data (as in, now I know what not to do versus framing it as a personal shortcoming).

“As an artist and an activist, I am part of an expanding creative community that is providing platforms for open and growing conversations about issues of discrimination and societal fractures.”

Your work is constantly being informed by life. How has the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement influenced brain space and any future works?

As we experience the tectonic shifts in society and its norms, there is a profound loss to grieve. The death toll continues its rise to record-setting levels never witnessed during periods of peacetime. How do we heal while building a new normal? Any belief in returning to what we once knew is delusional. But the pandemic has provided a reset—there is an openness to possibilities and to choices based on what we have learned. It is important to move forward, adapt, and connect beyond ourselves. We are an intertwined ecosystem of nature and human fellowship.

When my metaphorical wheels threaten to spin-off (which is often) I return to what I refer to as the guidelines of my “Daily Six-Pack.” This has nothing to do with beer, nor unfortunately the state of my abdominals. It is a set of intentions that ground me. They include meditation, healthy eating (which is more loosely defined these days), exercise, social outreach with family and friends, sleep discipline, and making art.

During early isolation, I had few art supplies available. So I spent hours on my iPad and drew on copy paper and whatever was available. The haptics of drawing and painting centered me in a generous way. That early work focused on the images of the Buddha. The empty center of the sculpture eerily echoed the shape of the actual bomb clouds. I continue to obsess over the positive and negative spaces. Maybe I am looking for some sort of clarity through the layers of materials and mediated images. I imagine a phoenix rising from the center of the ashes. Maybe there is hope to be apprehended from the destruction.

As for recent current events and the igniting of the Black Lives Matter movement, it is an essential reckoning about the immorality of racist behavior. It is about our American system and the ways in which it has reinforced exclusion and injustice. The cruelties inflicted and harsh inequities have weighed down our nation. For me, it starts with an unflinching assessment of my own blind spots and biases. I have sought out the wisdom of black friends and frankly listen, much more than I talk. How can I effectively open doors to a fuller understanding and help change structural biases? As a white woman of privilege, what access can I provide to the people, and to the power positions in corporate, social, and educational realms? As an artist and an activist, I am part of an expanding creative community that is providing platforms for open and growing conversations about issues of discrimination and societal fractures.

I know we need clear strategies and disciplined accountability in order to make change. And honestly, at times, I am embarrassed to be a white American. But I know that the need to correct our course is urgent. It is a necessary priority for me and I am committed to learning, reflecting, and activating change. We all must work to elect able and courageous leadership and perform our most important duty as citizens via the ballot box.

What is your mission in education at the Museum of Modern Art?

I serve as chair of MoMA’s Committee on Education. MoMA’s original charter, dating back to the time of its founding in 1929 was in education. The foresight of Abby Rockefeller and her fellow female founders was to provide exposure and knowledge about modern art to a larger community. Endlessly, I feel awe and reverence for their brilliant vision and execution. Remember this was the start of the depression. They gave the arts a premier position, as something powerful and essential to our human society. My work with cave signs, some dating back 40,000 years, reveal a consistency in the appearance of human marks and their value in conveying information and expressing ideas. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs misses the literal writing on the wall of our species—a need for the expansive language of creative expression.

MoMA’s education programs and the artist educators have been leaders in the cultural field on a local (schools, and community programming) and global level (with digital learning platforms). Last month, online courses recorded 1.2 million subscribers. While content and delivery channels have changed, the commitment of excellence to the theories and practices of learning has remained consistent. With its wide aperture, the education department observes and interacts closely with our audience.

Just this past March, the Education Department launched a new audio-guide series called “Beyond the Uniform,” led by the artist Chemi Rosado Seijo who collaborated with MoMA security officers to tell personally meaningful stories about works of art from the officers who protect them every day. Visitors can listen to novel stories and insights from voices not typically heard, and as artists themselves, they have unique perspectives on the Museum and its collection.

How has the pandemic affected MoMA this year?

The ground under MoMA, like most cultural institutions, has shifted during the pandemic. In this space of anxiety and opportunities, we are reimagining our role in a situation where there is altered access to physical space or objects. How can we be of service to others in such difficult times? The discussions are being held in real-time as we think about adaptations. Undoubtedly, the answer will be in the digital space where we can continue a connection with our audience and expand it further with content. I expect much of it will be driven through educational platforms.

All institutions need to more equally reflect the communities which they serve. Museums can no longer be defined by edifices but must be places of convening, interaction, and learning. MoMA’s history has largely been informed by the scholarship of a predominantly white western canon. There are more voices and thoughts to be heard. We continue to evolve in our understanding. The Education Department and its educators are invaluable resources for growth.

What advice would you give to artists hoping to branch out from being a creator to getting involved with community initiatives and leadership positions?

My advice would be to live courageously. It is now that the artist must resolve to take action. The studio, the protected sanctuary of making, must turn outward, to manifest your vision. You must join the conversation to move forward. Taking a stance, sharing your work, or even simply bringing an idea into reality can be daunting but it is necessary to the social language of art. After honing your senses and absorbing the moment, you must act. The action, even a simple pencil line or advocating for the creative community, is an act of preservation, a physical record of your experience.

In the Atelic way, the senses are attuned to the environment. As art is typically thought of as a visual experience, if you didn’t have eyesight what kind of art do you think you would create and patronise?

I aspire to the “atelic” from the Greek word a telos or “without end.” There are plenty of things that have necessary deadlines and require completion in life. Imbued in the atelic, is a potential for continuous growth and mastery. Perfect yoga sessions, ski runs, or art processes are unattainable, but the potential for fine-tuning always exists. I wonder if that is the lesson from Sisyphus every day when he finds himself back at the bottom of the hill with that rock. Maybe he hopes to improve his journey and or find a way to break his ungodly curse. With a nod to Sisyphus, that is how I roll in life and in my studio practice.

“Life’s journey is difficult and full of heartbreak. Paying attention to the sensorial helps access the richness and sacred around us. Nature is an antidote to the stresses of life.”

I have heard that when one loses the faculty of sight, other senses take over. So I would have to come to know what was different for me. Probably, I would shift to the tactical indices that could inform me about the proximate environment and what is contained within it. Making marks has always provided grounding and some sense of where I am. Beyond that, I would look to the generosity of Mother Nature that provides opportunities for nurturing connections with others and with nature.

You’ve spoken about your appreciation for Leonardo DaVinci’s unification of art and science; are there any contemporary artists that you feel embody this spirit?

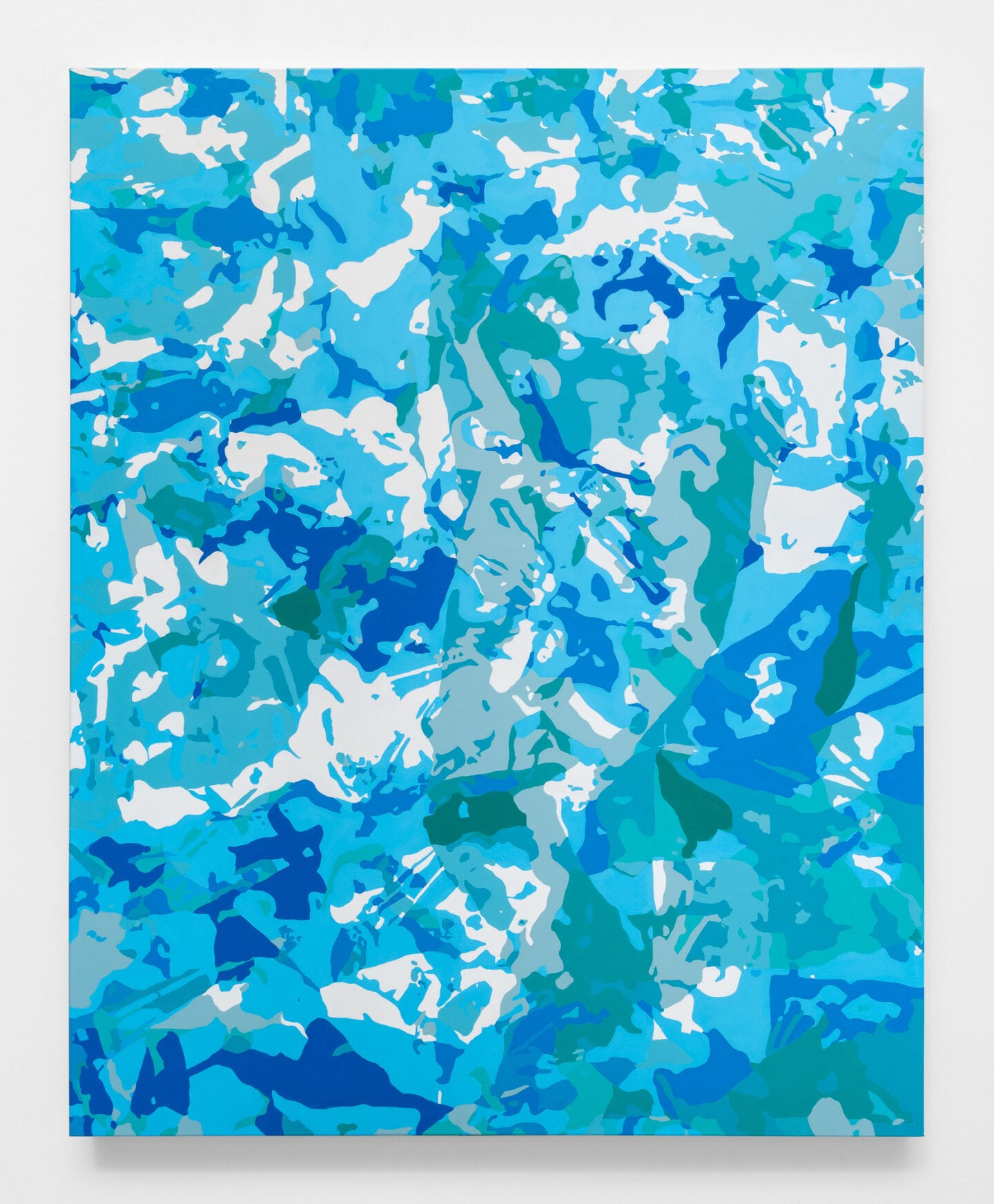

Leonardo was a genius polymath. His understanding of the optical nerve and how we see, his powers to observe and translate them on paper, and his scholarly investigations leave me speechless. He understood how others perceived images, which informed his work. His was attuned to the invisible, and his senses must have been highly tuned to be able to render things like air currents or nerve impulses with such accuracy. His patterns of swirling and turbulent water-inspired my Anemos series.

I can’t really conjure up any contemporary artist that compares with Leonardo in breadth and execution of visual ideas. It is likely that artists and scientists employ Leonardo’s combination of insatiable curiosity and exceptional abilities. His journals are roadmaps to his interests and way of thinking and ultimately to his process.

What are some ways you’ve used art to respond to social or political issues?

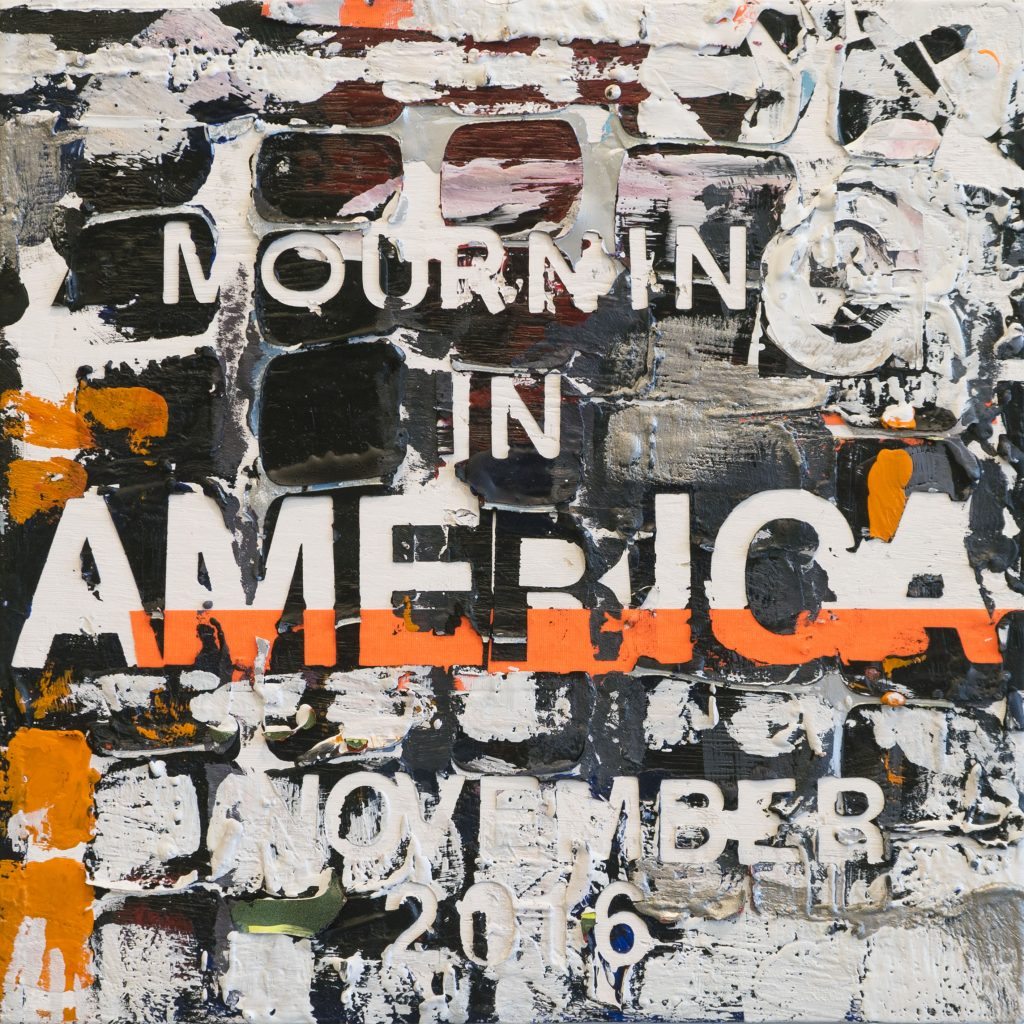

I am so grateful to be an artist. I remember on the morning after the Presidential election in 2016, I had no words. I went to the studio and painted searing hot encaustic on raw wood to write “Mourning in America.” The melted and burned detritus became a chaotic assemblage called “Alternative Facts” and layers of black wax took on the appearance of a funeral veil that declared “Orange is the New Black.” Art-making provided space to process my grief and the deep anxiety of the suffering to come. I later contributed these works to an auction for Planned Parenthood.

I experienced similar emotions last February at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. My work was being exhibited as part of the For Freedoms Congress at MoCA. (Check out the ongoing work of For Freedoms, an artist-led activist organization that is leading important civic and social justice conversations.) I happened upon an exhibition about survivors of the tragic bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. A moment in history I am forever drawn to because of my father’s role as a navigator in a B29 in the Cold War, which I investigate through my Bomber Series. The exhibition at the Japanese American National Museum revealed so much unnecessary suffering and horror. It was the statue of a partially melted sculpture of Buddha that made me gasp. Its metal was disfigured and melted by the atomic bomb. It embodied the moment as an indexical witness to the power of the destruction. I could not shake its hold over me.

I photographed the Buddha from multiple angles. Just a few days later, the realities of the pandemic and the necessary isolation hit. Like the rest of the world, I felt untethered and helpless in this space that was disrupting familiar behaviors and undermining the artifice of what we believed was controllable. Abounding fear and anxiety were collectively palpable. My learning from the Buddha had just begun. My understanding deepened along with an empathetic connection with a society that had been harmed and damaged beyond recognition. The suffering was unnecessary and the chaos destabilizing. There were understandable accusations and blaming, demonization, and stories to rationalize (sound familiar?). But the transcendent gift from the Japanese people is clear; to always take action and move towards healing even in unspeakably altered terrain.

One survivor of the blast in Hiroshima (who went on to become an acclaimed landscape architect) told me about the feeling of ecstasy he experienced when he witnessed the first sprouting seedlings. Nature shows the way. It reminds us through nurturing, fortified with a support system, we can adapt and begin again. With the pandemic not much is asked of us besides wearing our masks, keeping our distances, and washing our hands. We can handle these new daily requirements and thrive.