Gallivanting the Whitney Museum of American Art, Gertrude Style

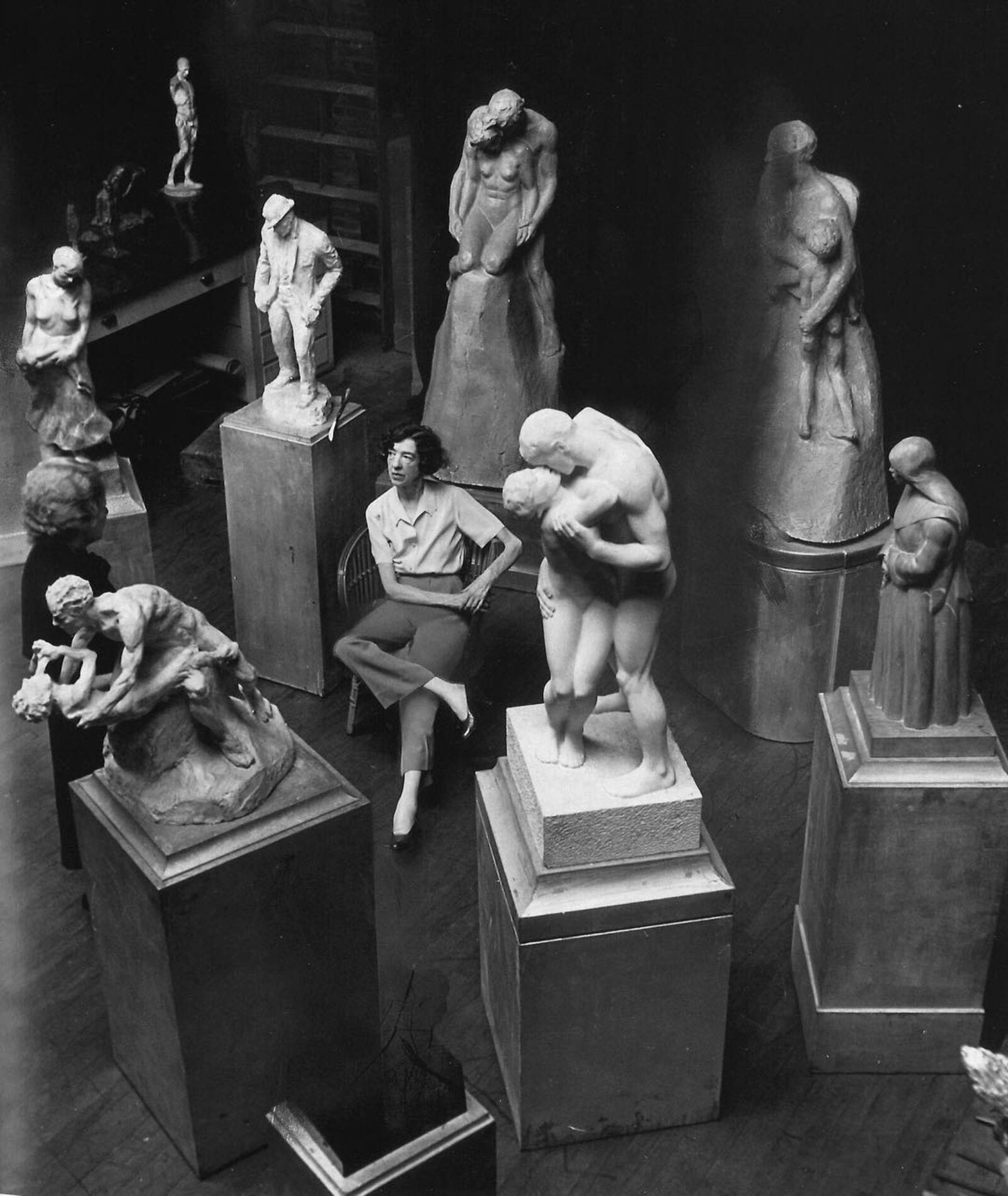

First called the ‘Whitney Studio Club’ in 1914, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s most important contribution was her lasting legacy in creating an artists’ club where young artists could meet and exhibit their works, which later evolved to be the Whitney Museum of American Art, now renowned as one of New York City’s most prestigious art institutions. Whitney began as a sculptor in her mid-twenties when she started to distance herself from the high society world into which she had been born. She was determined to establish herself as a creative artist, though her wealth and being a woman in a world of mostly male sculptors made it difficult for her to be taken seriously. As both an artist and a patron, she devoted herself to the advancement of women in art, supporting and exhibiting in women-only shows and ensuring that women were included in mixed shows.

Four generations of Whitney women have served as presidents or board members of the Whitney Museum of American Art over the past 100 years, as it grew from a small, private club into a major public institution. With previously exhibited legendary artists like Carmen Herrera to Toyin Ojih Odutola, we spent the afternoon “gal”-livanting around the Whitney to create a round-up of our top women artists currently featured in its archives.

In ‘Orange Mood,’ Helen Frankenthaler thinned acrylic paint to the consistency of watercolor in order to create large, curving expanses of color through which the weave of the canvas remains visible. Like Jackson Pollock, she placed her canvas directly on the floor and poured paint from above, largely without the aid of a brush. Frankenthaler used color as her painterly language, but she never entirely abandoned representation. Although the references can be subtle, her paintings consistently evoke nature. The undulating forms in ‘Orange Mood’ relate to a simplified landscape, with zones of color recalling different emotional states. Hue and shape convey place and feeling. “I think of my pictures as explosive landscapes, worlds and distances, held on a flat surface,” Frankenthaler once stated.

In the early 1960s, Emma Amos began to create imagery that shifter fluidly between abstraction and representation. She was the youngest only female member of Spiral — a New York-based collective founded by Charles Alston, Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, and Hale Woodruff in 1963 to consider art’s relationship to civil rights. Amos resisted the idea of a singular Black aesthetic, which put her at odds with artists who insisted on direct, often figurative, depictions to address racial politics. As she later stated: “Every time I think about color it’s a political statement.”

In paintings like ‘Jigsaw,’ Miriam Schapiro explored how geometric abstraction could serve both formal and feminist concerns. Here, she experimented with the spatial effects of color, using hues in this painting that she described as “blinding and high keyed, enough so as to optically distort the form.” Although she would not become explicitly associated with feminism until after 1971, when she advanced the Feminist Art Program with Judy Chicago at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), such early paintings contain oblique references to the body and gender identity. At this time, she often adopted geometries that resembled apertures and passageways evocative of the female body. If a human figure is implied in this painting, however, it is hard to read as a male or female — a rebuke of the idea that gender can be simply defined and categorized.

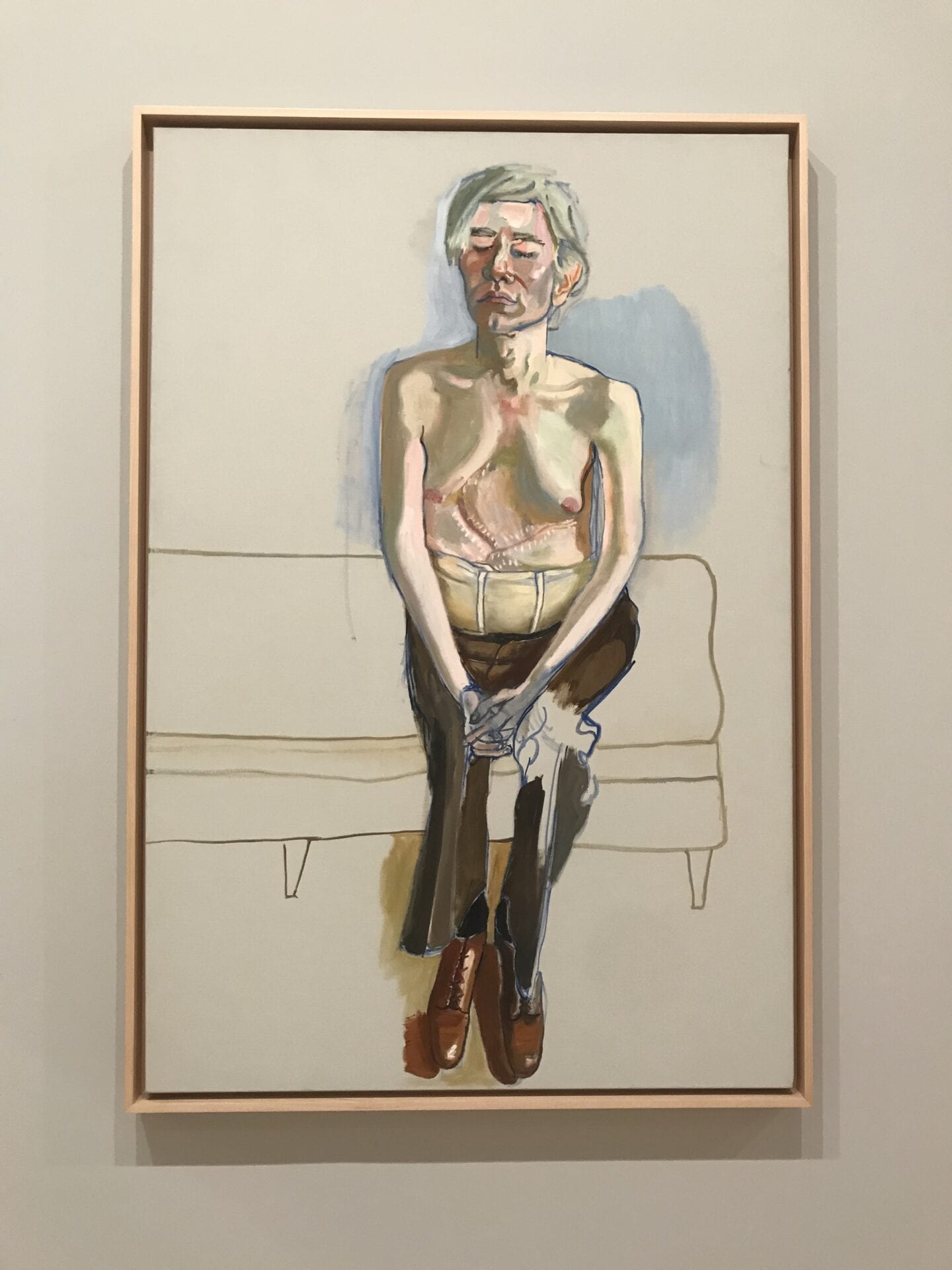

In this painting of Andy Warhol, Alice Neel captures a vulnerability rarely glimpsed in her subject. Known for surrounding himself with throngs of followers and donning a variety of guises from wigs to makeup to sunglasses, Warhol once remarked, “Nudity is a threat to my existence.” Here, however, Neel depicts him with his shirt removed and his eyes closed, displaying his surgical scars and the supportive corset he was forced to wear after being show in 1968. In her hands, the artist famed for his cool detachment becomes human — 1970, Neel said of her fellow artist: “I found him personally very kind and reticent and even the economy of my technique in the painting tries to convey this.”

Ruth Asawa’s wire sculptures brought her prominence in the 1950s, when her work appeared several times in the annual exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art and in the 1955 São Paulo Art Biennial. In 1962, Asawa began experimenting with tied wire sculptures of images rooted in nature that became increasingly geometric and abstract as she continued to work in that form. “Ruth was ahead of her time in understanding how sculptures could function to define and interpret space,” said Daniel Cornell, curator of the de Young Museum in San Francisco. “This aspect of her work anticipates much of the installation work that has come to dominate contemporary art.”

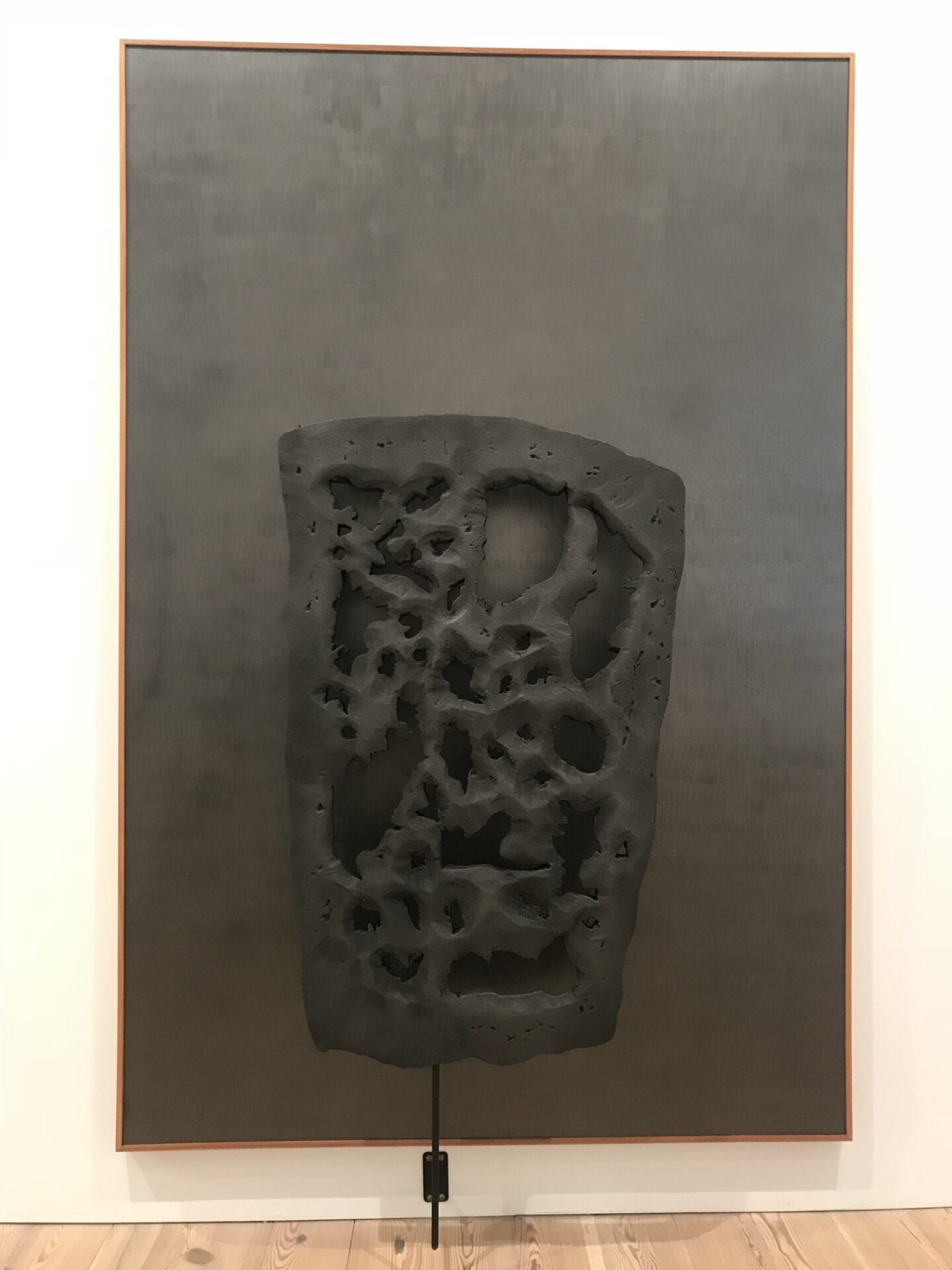

How can one understand an ancient Indigenous language that has not yet been deciphered? Gala Porras-Kim seeks to address this question through visual vocabularies that lie beyond historically colonialist disciplines such as anthropology. Here she focuses on La Mojarra Stela 1 — a stone, carved with the untranslatable characters of Epi-Olmec script, that was discovered in 1986 and is now in the collection of El Museo de Antropologia de Xalapa in Veracruz, Mexico. Porras-Kim’s collection of works propose different approaches to the question of the stela’s meaning. For example, a reflective graphite panel in La Mojarra Stela 1 negative space recalls obsidian mirrors that were sometimes used in ancient Meso-American divination methods to interpret reflections. In other iterations Porras-Kim creates distance or draws attention to the space between characters, allowing viewers to draw their own associations, imagining new ways to translate lost languages.

Captions courtesy of the Whitney Museum.