Frida Kahlo: An Icon of Female Empowerment Comes to Palm Beach

This season, there’s been a lot of buzz surrounding the Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Mexican Modernism exhibition at The Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida. This major exhibition incorporates more than 150 works from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection including paintings, works on paper, photographs and time period clothing.

“Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Mexican Modernism is among the largest exhibitions of Mexican art that we’ve ever presented,” said Ghislain d’Humières, Director and CEO of the Norton Museum of Art. “We are thrilled to have the opportunity to exhibit works by esteemed artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera in the context of their peers and in conversation with our collection. Beyond presenting outstanding art, this exhibition reflects the relationships and tastes that the Gelmans shared with the artists in their orbit. Offering audiences the chance to view these works through the lens of their collection, the exhibition suggests fresh modes of experiencing beloved works of art.”

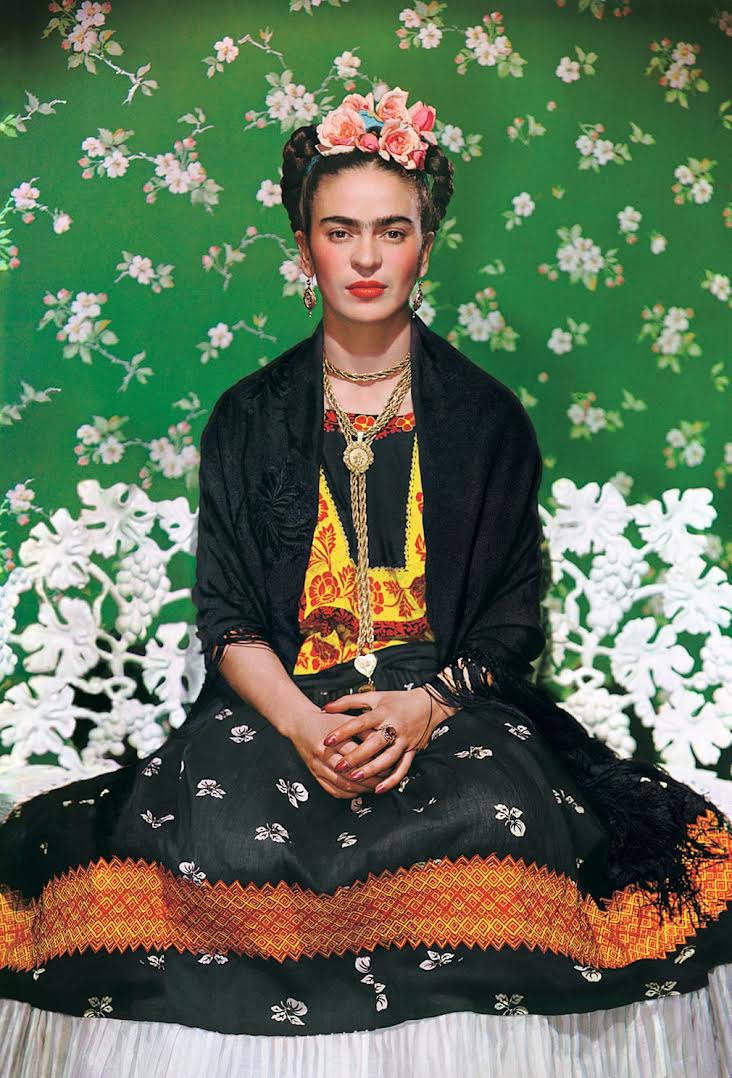

Tracing the influence of Mexicanidad, the belief that Mexicans could create an authentic modernism by exploring the country’s indigenous culture, the exhibition reveals the centrality of this idea to Kahlo’s iconography, manifested as a distinctive brand of magical realism colored by Mexican folk art. Even her adoption of traditional Tehuana clothing reflected Kahlo’s desire to establish a connection with ancestral Mexico while expressing a cross-cultural identity that honored her heritage and status as a modern woman. A selection of period vintage dresses sourced in Mexico, which include colorful embroidered blouses and full skirts, is on view in the exhibition, enriching the presentation’s examination of her art in the context of her life and persona.

Besides being shown in one of the hottest art and real estate markets in the country right now, the Norton Museum has done an excellent job in local outreach, advertising this exhibition through many venues, from social media to the new Brightline train system which connects Palm Beach to Miami – where Art Basel takes place, and there’s a larger Hispanic population. To encourage a Latino audience, the caption of each work is offered in both English and Spanish.

This exhibition also attracted a lot of attention after the Frida Kahlo painting, Diego y yo made history at Sotheby’s Modern Evening Sale in November selling for a record $34.9 million for art by a Latin American artist (to an Argentinian collector named Eduardo F. Constanti). It’s clear the interest in Frida Kahlo has now surpassed her male partner, Diego Rivera, and raised the bar for the Female Latin American Modern Art Market. The previous record-holding sale was held by Diego Rivera titled, The Rivals, which sold for $9.76 million in 2018.

Originally from St. Petersburg, Russia, Jacques Gelman was a film producer during the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema. His wife Natasha left Austria, Hungary to live in Mexico before WWII. After Jacques passed-away, Natasha continued to collect art to add to their collection, eventually giving it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1998. The collection included ninety-five works composed of Mexican Modern Art, eighty-one European Modern Paintings, drawings, and Pre Columbian sculpture.

In addition to Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, The Gelmans had a strong relationship with other leading art figures who had arisen after the Mexican Revolution. The couple were friends with Mexico’s creative community during the mid-twentieth century which is evident by the numerous portraits of them made by these artists which are featured in the collection, including: Manuel and Lola Álvarez Bravo, Miguel Covarrubias, Gunther Gerzso, María Izquierdo, Carlos Mérida, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Juan Soriano, and Rufino Tamayo.

The collection explores these artists’ distinctive interpretations of modernism as expressed in themes of nature, home, and family in photographs and easel and large-scale mural paintings. There are also photographs in the collection which not only show the influence Frida and Diego’s modernistic approach had in Mexico during this time, but also help us to understand the influence they had on each other. The photographers included in this exhibition are: Lucienne Bloch, Imogen Cunningham, Juan Guzmán, Graciela Iturbide, Nickolas Muray, Edward Weston, and Guillermo Kahlo—Frida’s father.

One photograph of note was taken in the New York studio of Nickolas Muray, who photographed celebrities around the world for magazines like Vanity Fair and Vogue. Muray met Kahlo in 1931 and had on a “volatile” romantic relationship that lasted nearly a decade. Muray’s photographs of Kahlo are among the most well-known images of her, capturing her confidence and poise in vivid color. Muray was also a supporter of her work, purchasing her painting What the Water Gave Me (1938) from her exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in 1938.

We as women can relate to the multiple struggles Frida faced throughout her life. For example, the tumultuous relationship she had with her husband, her bisexuality, her rebellious feelings towards social norms, and her physical and emotional pain. As a child, Frida suffered from polio and at 18-years-old suffered a tragic bus accident which shattered her pelvis and spine preventing her from baring children. This was something she longed for her entire life and a theme expressed throughout her work. The many complexities shown in her artwork are still relatable for women today which is why in part she has become one the most well-known female artists of our time.

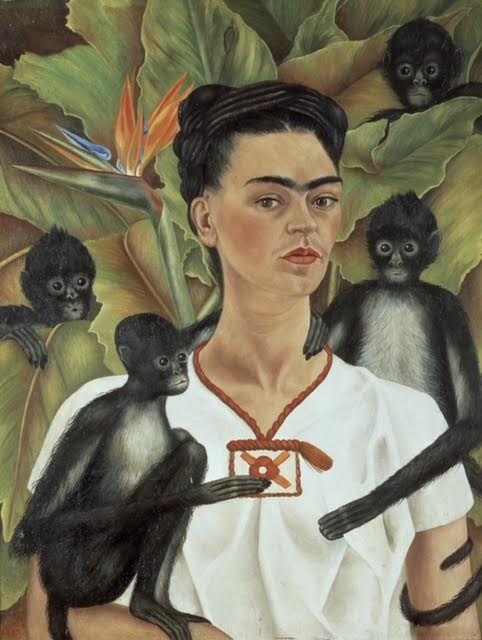

Through Frida’s work, we can see both her love for Mexican heritage and her desire to express herself as a modern cross-cultural woman. For example, in her Self Portrait with Monkeys (1943), Frida incorporates the iconography of traditional Mexican fauna and flora with her avant-garde beliefs about facial hair on women, portraying herself as a strong modern woman, comfortable with her sexuality. In this exhibition, there are twenty-two works by Frida and eighteen by Diego. Frida was also a very political person. All these facets of her personality are deeply intertwined in her work, sometimes inconsistent, but revolutionary. It was particularly interesting how the curators of this exhibition chose to hang these works. Frida’s Portrait of Natasha Gelman (1943), next to Diego’s, Portrait of Natasha Gelman (1943). Even though they are both portraying the same woman at the same point in her life, they can be interpreted very differently. This juxtaposition helps show the difference between the artists’ perspectives on their subject, Natasha Gelman — the male versus the female perspective. In Diego’s portrait, Mrs. Gelman is reclining, made to look very seductive. She is posed similarly to the Neoclassic style of La Grande Odalisque (1814) by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, except clothed and made to look more glamorous. In contrast, Frida’s portrays her in a close-up, only showing her head, inviting the viewer to look deep into her eyes. It shows the power and depth of the woman.

Similar to the recent record breaking piece sold at auction, Frida’s Diego on my Mind —also titled Self Portrait as a Tehuana (1943), is prominently on display. This painting includes similar themes to the ones depicting herself with a powerful gaze and facial hair, wearing indigenous clothing expressing her love for the culture. In the middle of her forehead, there’s a painting of Diego Rivera’s face supporting how much he consumed her mind. The piece also serves as a symbol of the major political muralist movement in Mexico at the time and shows how politics consumed her mind, as well.

In Frida’s Self-Portrait with Monkeys (1943), she is surrounded by four monkeys she kept as pets in Coyoacán. Frequently described as “surrogates for her maternal energies,” the monkeys in this work may allude to her role as a mentor as she began teaching at La Esmeralda, the Ministry of Public Education’s art school, the previous year, according to The Norton. When her declining health stopped her from teaching, she invited students to meet at her home, forming a small group of four regulars who became known as “Los Fridos.”

We recognize Frida’s strength painting these pieces from her bed – a fearless woman who pushed the boundaries of her time, faced her struggles head on, dared to be unconventional when women weren’t encouraged to be. Frida Kahlo is an icon for feminist empowerment, and through the many remote and in-person programs, including curator conversations, art making, book discussions, and special tours the Norton has hosted throughout this exhibition, her art has been inspiring to many in Palm Beach and beyond.

Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Mexican Modernism was organized by the Vergel Foundation and MondoMostre in collaboration with the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura (INBAL). It was curated by the Vergel Foundation curator, Magda Carranza de Akle, and for the Norton by Ellen E. Roberts, Harold and Anne Berkley Smith Curator of American Art. Roberts also led a symposium called, Modernism in Mexico, which included panel discussions with Mary Coffey, Professor of Art History, Dartmouth College; Ramón Favela, Research Professor Emeritus, UC Santa Barbara; Anna Indych-López, Associate Professor, City College and the Graduate Center, CUNY; and Stephanie Weissberg, Associate Curator, Pulitzer Arts Foundation.

Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Mexican Modernism from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection remains at The Norton Museum until February 6, 2022.

For more information on museum hours, tickets and safety protocols, please visit: www.norton.org