Delphine Diallo: Reframing the Black Woman’s Body Through the Female Lens

A French-Senegalese visual artist and photographer living in Brooklyn, Delphine Diallo combines artistry with activism, pushing the many possibilities of empowering women, youth, and cultural minorities through visual provocation by using analogue and digital photography, collage and illustration, 3D printing and virtual reality technologies as she continues to explore new mediums. Mentored by acclaimed photographer Peter Beard and currently represented by MTArt Agency in London, Diallo’s powerful portraits unmask and stir an uninhibited insight that allows her audience to see beyond the facade. The artist says: “We are in constant search for wonder and growth. I believe all humans, regardless of racial and geographic differences, share the same collective pool of instincts and images, though these manifest differently due to the moulding influence of culture. The time has come to go beyond the individual mind and relate our common universal connection to each other. We must collaborate, support, inspire, teach and learn together.”

From our recent IG Live hosted in partnership with Studio 525’s ‘VOICES’ exhibition curated by Anwarii Musa in Chelsea, host Natasha Roberts delves deep into Diallo’s thought provoking messages through a virtual studio visit with the artist.

Delphine Diallo: As a French Senegalese woman, I contend with the stereotype of what the black woman should represent. I’ve been a graphic designer, art director, video editor and now a professional photographer for the past 10 years, and yet, throughout my experience working in the industry, I was seldom given credit as the woman doing the work. People still ask me, at 42: Are you a model? In everyday professional life, I’m too often seen as an object, the fantasy of the exotic black woman. Even now I still have to answer ‘How did you get the job?’ It diminishes not only the work I have done, but who I am.

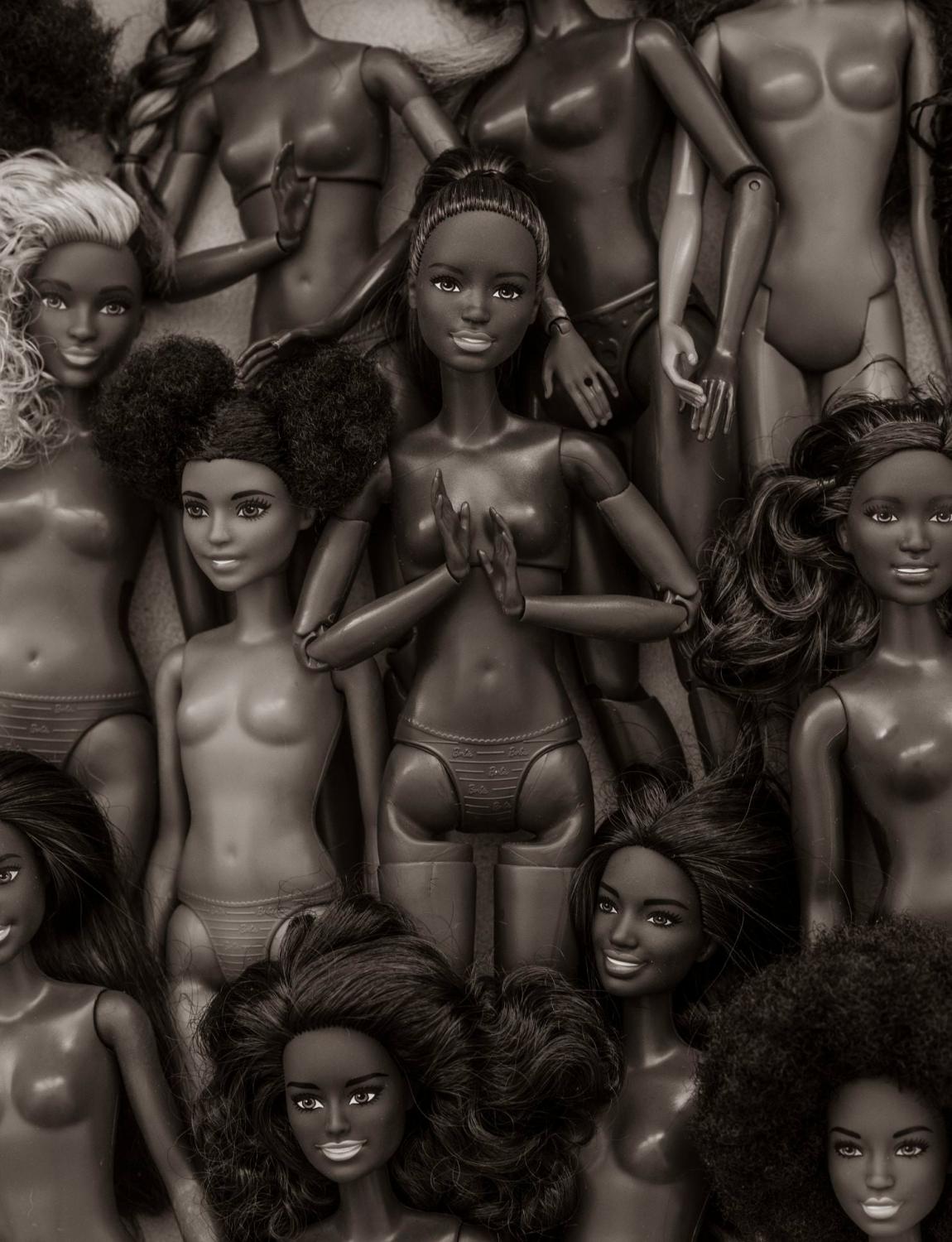

When we are looking at the success of stars like Beyoncé, Rihanna and Nicki Minaj and the archetype they represent, we see how over-sexualized their bodies are. That focus can bring about real pain in girls of color who don’t look like them. I respect the work of those artists, but I’m sick of the perpetuation of ‘body first, mind after.’ When I began exploring how to represent the black woman as an object, I didn’t want to photograph a real woman because I wanted the focus to be the woman as a subject, not as an object.

“I started to research the different types of black dolls the toy industry has created through the years. To my surprise, Mattel’s Barbie had the most choices: curvy, skinny, light-skinned, dark, big hair, braids, short hair, colored hair. Despite that range, the dolls ultimately still represent preferences about the black body. Toys are for children to play with, but they can also carry their own messages.”

Natasha Roberts: So you graduated from Académie Charpentier School of Digital Arts in Paris, and then for 7 years were in the music industry working as a special effects motion designer, a video editor, graphic designer, and then exit your role as a corporate art director and decide to move to New York in an exploration of your own art practice. I’d love to know what was your ultimate moment of inspiration that caused you to go for it?

DD: It is something that everyone can relate to because it is a very human emotion. It is something in all of us that we are looking for this urge and emergency of living life fully and finding something that we love what we’re doing but also noticing how much work it would take to do it. For example, if someone is living to be an artist, that is not from day one to the other. If I had this dream and I had to do it for example, the first things that I learn, this voice would tell me “you know this is going to take you ten years minimum.” So it is a commitment – not through a company or a boss. First you need to find who you are, you need to study, you need to discover what is going on inside, and then from that understanding step-by-step every year, have a better understanding of why you are doing what you are doing, and how that can become sustainable for 40 years, for example. So that was my first inspiration, finding a space where I knew that I can live this life for 40 years.

NR: The female black body has been historically photographed primarily through the white male gaze and it is usually exalted through curiosity of otherness or as an object of desire. So being multi-racial or bi-racial it adds such a layer of complexity for others and for oneself when discusses identity. How do you unpack and counter that in your work which features mostly women?

DD: Being born in a patriarchal society, you are not aware of what has been taught to you and what kind of surroundings you have been raised in. The first understanding is to realize is that you are not what society wants to project, especially for brown-skinned women where everything is based on exoticism. And let’s say the hip hop era through the 90s – the hip hop industry becomes huge and proud of black people making money, but women had a certain role to play which actually was “We’re going to use the black woman’s body to make money.” I was born in ’77 so I grew up in this era, and I had a really hard time to identify myself to this and also having no almost role model outside of 3 or 4 stars, like Whitney Houston or Halle Berry. I was sick of not understanding what kind of role a French-Senegalese woman from Paris can play in society. Being a part of something for me was starting to understand that I had to understand my own body first, by practicing martial arts. I trained to understand what was happening to me and why I could not own my body, something was missing. Through the martial art training and through mediation and the discovery of mythology and wisdom of different backgrounds, my intuition guided me to then understand black women specifically and what is it that we have in common that we can’t figure out. This is where this work was born from, most of the pictures that you see in my work are my friends. It is a nurturing a process where hopefully when we get old they will come to me and say that it helped them.

NR: Tell us more about your motivation to give photographs versus taking them and this theme of empathy which is very important to you and more about your project Women of New York.

DD: This is where actually I am able to explain and express what “giving” photography is instead of “taking” photography, especially because myself during the project I didn’t know why I was guided by this intuition to change my relationship with the subject beyond my knowledge. My knowledge is like when I am photographing my friend I still know them and I am still selecting them so there is a gaze here where I am still making these empiric choices, like you are fitting my aesthetic. On this level, I am lacking a vision because I really draw my skills and my type of woman, like when I did Women of New York. I posted a call for every woman who feels that they want to be photographed by me. 140 women texted me back in two weeks, it was amazing, and it was not just black women it was black and white women who came. It helps me to understand my relationship with the New York energy which is very multicultural. Also realizing the women come to my space because they want to meet me and also because they want to have this very special photograph of themselves because I’m sure inside of themselves they feel respected.

If you tell me what would be the difference between big photographers and myself is that there is nothing big about what I do. I am changing the gaze, so indeed that will open the conversation to change the way that we actually use the photography as we say “use.” I started my journey and my work to try to understand what would be a great vision for [others], not for me. Even if I develop the work, it would be a failure for me if my friend doesn’t like the picture, it is very personal.

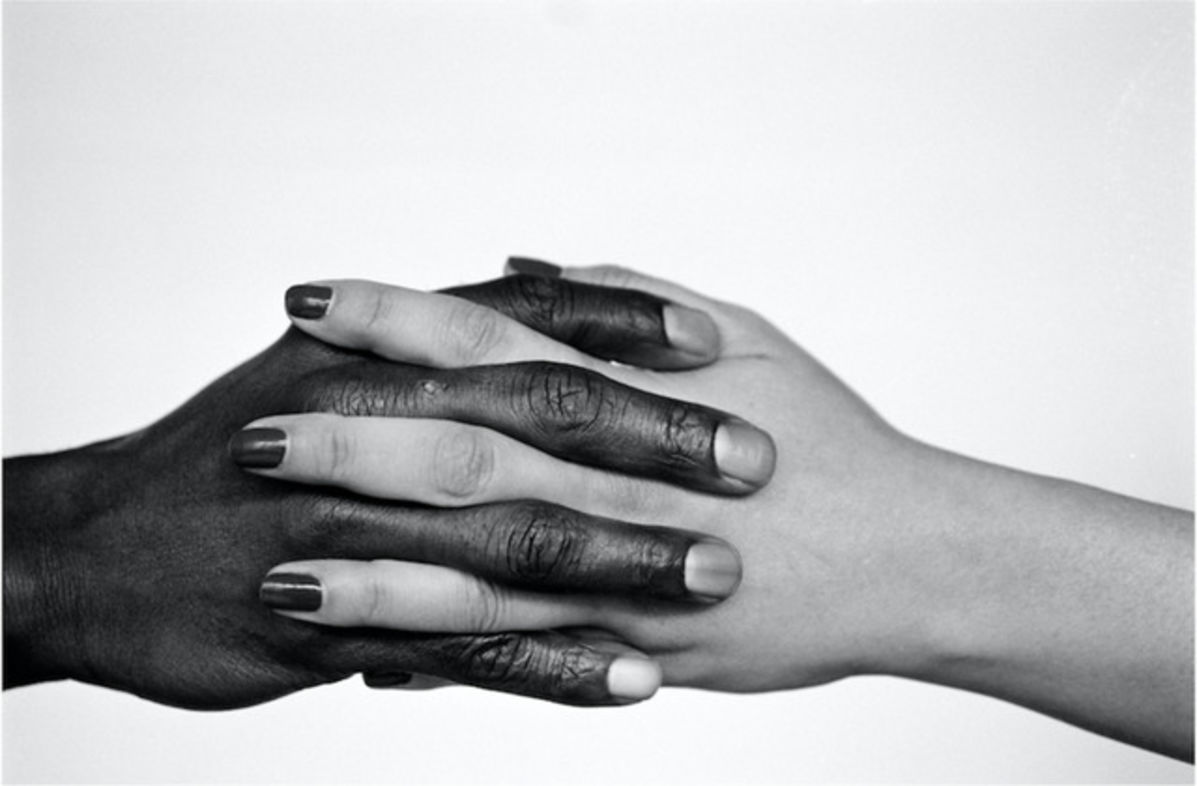

NR: Let’s talk about the piece, Unity, that is in the show. Can you tell us about the work?

DD: I photographed this work in 2011, but I really never posted it until this year. I worked for ten years and I have a lot of works I have never published. Sometimes I didn’t understand the full meaning right away but my intuition was to always run and work faster than my ideas sometimes. So I make them and I put them on the side, and I bring them out later. For this one, I had the feeling that I really needed to photograph a black man and a white woman together kissing each other and holding hands together because I want to see my parents. I never saw a picture like this in fashion or documentary, or National Geographic, you know the artistic vision of unity – not just pointing that this is a multiracial couple.

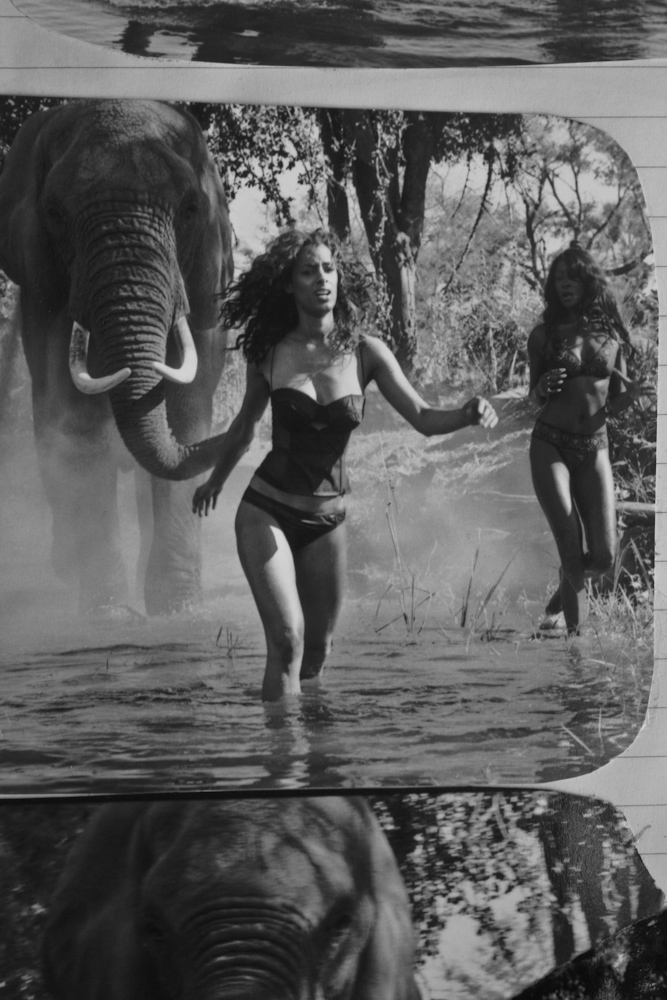

NR: And you yourself have stepped in front of the camera, and most notably for your mentor Peter Beard. Tell us about that and the most important things you’ve learned from him and that experience of being the model and flipping that relationship.

DD: This is how the transformation works. I was 31 and Peter saw me as an exotic woman, super photogenic and he wants to photograph me. And I’m 31, I was not in this world, I did not know that I could be photogenic, and I had never been photographed by anyone. I was in Paris so the industry of mixed-brown girl was popping in New York, even in the 90s, but not really in Paris. He showed me how for him I am beautiful and saw my reaction. He was a bit upset with my reaction because I didn’t really want to be a model. I was very surprised that I looked like this. And he kept insisting to photograph me and brought me to Botswana to be his creative assistant, and to photograph me on the location, because the periodic calendar [he was working on] asked him to photograph only almost white women in Botswana in the middle of Africa. He was really upset. So he asked me and a very beautiful model to come with him before the shoot so he could have a photograph of wild Africa with at least black women, not white women.

So I was entering a space and a world. I was a part of it but I did not ask for it. They were very upset that [Peter] photographed me for the calendar, so they asked me to leave the camp. So as a black woman they saw me as sleeping with this man, or as an object, without knowing my creative talent, pushing me to the side and asking me to take a plane home. I had to digest this, and Peter tried to protect me, but if you have an entire production team against you, you can’t stay. Especially if everyone is white and you are the only black woman and they don’t want you there, it is very painful. I kept this to myself for years. But now I found the story and the narrative of [how this moment was] a lack of respect. I have very good education, I am creative director, and I did all of that before I met him. So at least they should check on me before they judge me. So this is where everything started for me, like a rage of being tired of having a sticker on me because I look like this.

NR: So the first time you visited Senegal you were a pre-teen to see your grandmother and had a new experience to visit a matriarchal-dominated family. What was like that experience like for you and how has your relationship with Senegal changed as you’ve grown as a creative?

DD: I was born in the Western world and I am a Westerner, and hopefully we will start having those conversations even as black people, how our brain has been conditioned to think like a Westerner, to eat like them, even though we have different DNA. So my first encounter with my grandmother was beautiful because my full name is Delphine Diaw Diallo, and the middle name they give you in Africa and a lot of countries in tradition is the name of your spiritual ancestors. So I had been given the name of my grandmother, so indeed I have my grandmother within me. It is like the blessing and the passing on of the ancestors. When I met her at 12, I was making the line because everyone has to see her once a month and there is this big line just to talk to her because obviously at 12 I thought she was giving answers and advice to everyone. When it was my turn, I saw this beautiful amazing energy of a matriarch with the feeling of abundance and holding her hand to my head and blessing me. So when she did this, she actually transferred the blessing and the gift of the matriarch to me. So when I grew up and became this strong woman because I’ve always been an athlete, I always felt that I had this energy of matriarch, which doesn’t mean you have to have kids, it means I love to inspire my girls and push them to be the best of themselves because I saw the good in people. She gave me that, and I have that from her. And from my mom I have artist and sensibility that comes from her. So this is very feminine energy that I have integrated into my work.

I felt like I wasn’t special. People can see the process, but I felt like so many women were feeling the same way I felt. So in my journey of transformation and fighting and challenging darkness or whatever you call it, I am calling upon the work of the women to come to unite. It is like, here is my skill, and I bet you have this skill too and this skill can be career, speaker…etc. The crew of women that I surround myself in New York are better than any woman in any movie I’ve ever watched. We are not entertaining people anymore. We are living a dream that we’ve never seen before, and I think that makes a big difference within the narration.

NR: So I know that you are represented by an amazing agency based in London founded by a woman…

DD: Marine [Tanguy] came into my life last year and that was an amazing encounter. I was doing shows and meetings with a historian in Paris and I discovered this great agency who was changing the game in the art industry. They finally understood what was the core of the commitment for us as we find an agent, it is like we have a voice. There is the work, but the work is an excuse to go and bring to society and amazing dialogue of change. Marine is the one who understands it and puts it into the art industry as an investment, which I hope more people will understand that we are, not just me but all of my art friends. We are an investment because we never stop to change and challenge [ourselves] to break the boxes of conditioning.

NR: So tell us what you are working on now. Are you working on any new types of material or experimenting while we’re all on lockdown?

DD: Recently I posted this work with an amazing metal worker. This is my second work with a craft person where it is metal and it is an artist from Senegal. It is a complete piece with bike chains and bike pieces. I have taken pictures of me in it, it goes on my body. I drew this in my head with this artist. I want to work with craft people from this background, so this is my next work. Also in New York, I have access to an African art collection so I am now transmitting within the black woman body the strength of the ancestors. So this is my work right now, we are shooting every week.

NR: So you said that your work won’t grow until you change your relationship with space and time and you were speaking about relocating to Senegal. Is that still the case?

DD: Yes, definitely. I might stretch the time because it is an interesting time in New York right now and I can’t deny that I learn a lot. The election is going to decide how fast I am going to move or not. Definitely the move to Senegal is imminent, which mean sit is exciting because I don’t know what kind of work I am going to do but I know that I am ready for a different landscape though (more nature, very simple, people around me, not just always going to openings and meetings an drinking and going out). That was me a long time ago, but now I wake up, I meditate, I make art, I cook, I see good friends, and that is pretty simple.