Collezione Taurisano on the Evolving Role of Art Collectors and Empowering Artists Around the Globe

With a family collection filled with a majority of female artists, Italian art collector Sveva D’Antonio talks to us about the Collector 3.0 – the importance of being engaged with artists throughout their career.

Gone are the days of art collectors only buying work and letting it sit in storage. Italian collectors Sveva D’Antonio and her husband Francesco Taurisano actively advocate for collectors to invest in emerging artists long-term from every angle of their careers and watch them prosper. From Brazil, New York, Los Angeles, Paris, London, and Berlin the duo has transformed their traditional family collection beyond Italy’s borders into one that fosters international contemporary artists whose works are inspired by socioeconomic and political issues.

Breaking from the old-school ways, Collezione Taurisano serves as a platform that works to support artists from the ground up. They not only acquire work, but they also assist with funding artists for their exhibitions. In doing so, D’Antonio says she is able to build a meaningful relationship with the artist and gain a greater appreciation for their work. Especially now through the crisis, Collezione Taurisano has organised acquisition awards, art fairs, artist talks, performances, presentations, and more – all in an effort to support artists throughout their career. The majority of these artists included in the collection are women, who D’Antonio suggests are more powerful in sharing their messages within their art.

“I think that now more than ever the role of collectors are more like custodians rather than buyers,” D’Antonio says. “I see collecting has a big responsibility because we became a very important actor in the art system and we have to support artists because less and less institutions support them in the way they would like.” We spoke to D’Antonio about her favorite works in the couple’s growing collection and what inspired them to choose these artists.

What are some political and social issues that the artwork you collect focuses on?

We collect artists from all over the world. Every artist that has a social, political, or economic engagement, and most of the time it has to do with the place they come from. We have an artist, Núria Güell, in Barcelona for example. She is Spanish with a South American background and she was talking about La Feria de las Flores which is this market of female adolescents that takes place every year in Colombia. In this market these female adolescents are sold for very few dollars. It’s crazy because the name La Feria de las Flores means “flower market” so the flower market has a meaning of tenderness, of fragility, of virginity but at the same time it’s something very brutal and violent. Her work consists of interviewing these women and trying to understand why they were doing it and who forced them to do it, and the outcome was a series of pictures and a video.

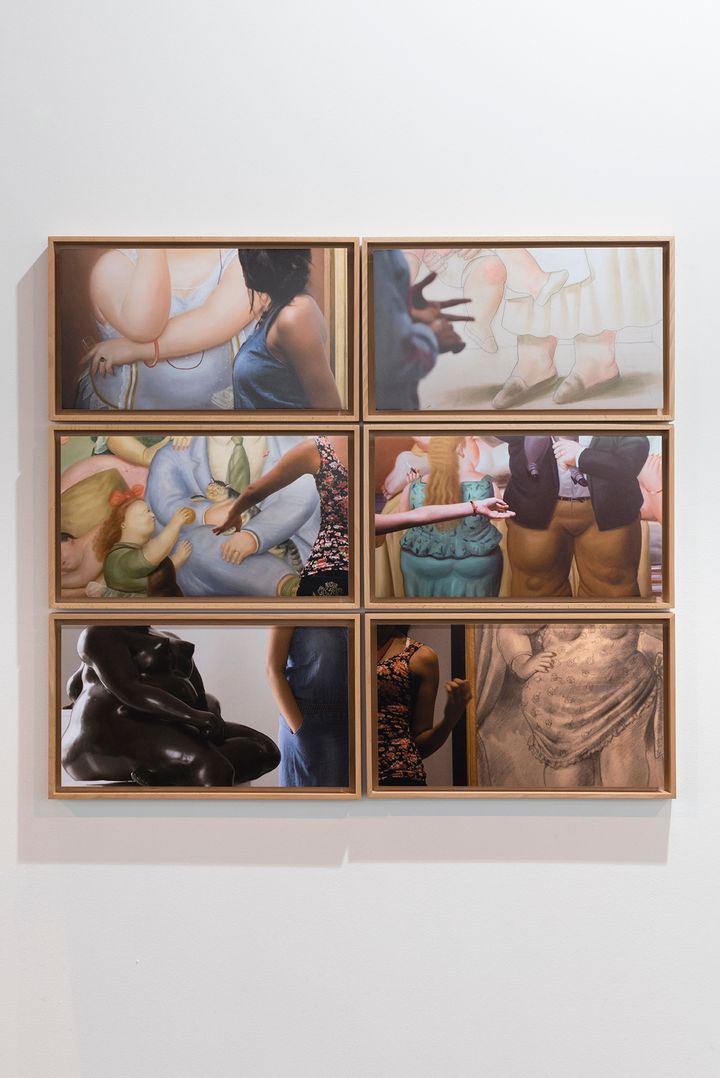

In Colombia, Botero has a very masculine representation of women. In Botero’s paintings, men are always bigger than women, so these women were explaining their situation in front of Botero’s paintings. I think it was a very interesting overlap between the paintings created in the past and the women in their contemporary situations.

Mineral pigmented print on photographic paper mounted on passe-partout

There is Clara Ianni, a very young Brazilian artist who studied philosophy at the University of Saõ Paulo. She was represented by Galeria Vermelho, and created a montage that revisits the military regime in 1965, Arena Conta Zumbi, because of course in Brazil all the most important political roles are taken by men. She was analysing the gesture of power of these politicians. We have in our collection these two series of photographs where she isolates the hands of these men who are signing very important contracts in the Saõ Paolo government palace. It was something very powerful; it was only men, there are no women in the Parliament. It’s something very striking because they’re deciding the destiny of the population without even asking them what they were thinking about. You understand how the system of power is really something that is mysterious and hidden in this chamber of power that we cannot access. Still there is this strong military elite of men who are deciding the destiny of all the others, and this was a female artist who was doing this research. We thought this was very powerful as well. They’re always talking about something that is happening right now; I think it’s very powerful. Not all artists do this.

Artists have this tendency of thinking “I want to be eternal, I want to survive myself with my work forever, so I don’t want to speak about what happened today or yesterday because it’s much easier to be forgotten.” Instead, these artists are very brave because they understand that giving us their interpretation of what is happening right now is an incredible richness. We understand better or we understand from scratch because we don’t know. You know better than me that we receive the information that they want to give us and not the entire truth so sometimes artists reveal some secrets as well about our society. For us, this is very interesting as well.

What is your approach to finding these artists? What is the search process for you as a collector?

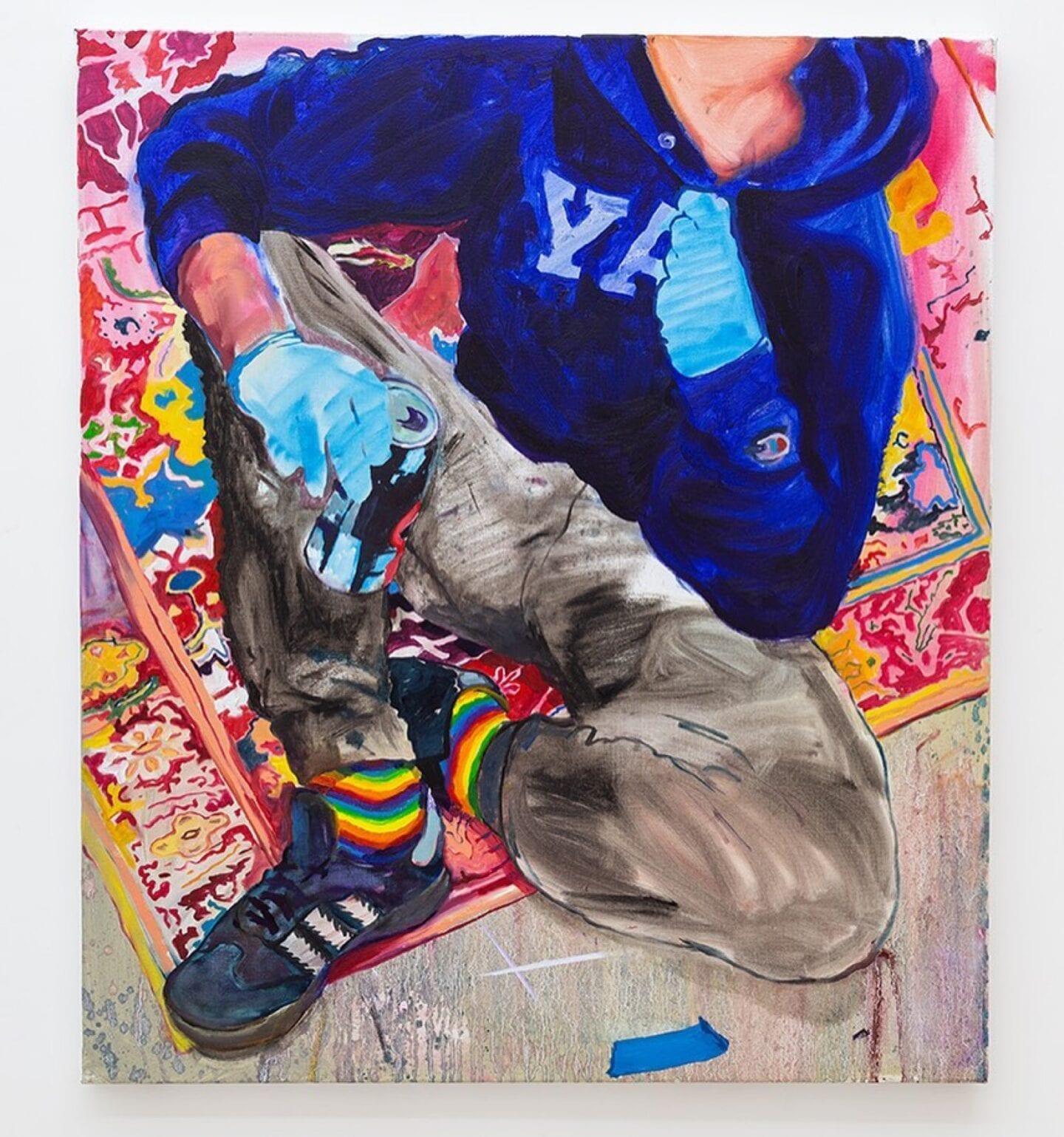

In the beginning we were much into art fairs. We thought that art fairs, since 10 years ago, have been a hub where you can discover new artists and have an experimental approach to their work. Instead now it is less and less. We love to discover artists through galleries. They are like a key actor in the art system, so we are always keen to hear from the galleries’ voice, the new artist they’re looking for or why they’re rediscovering an old artist. We have long-lasting relationships with galleries all over the world: Brazil, New York, Los Angeles, Paris, London, Berlin, to name just a few. But we really trust them, because it’s their role, they have the competence to do it. And when we can, we try to travel all over the world, like Frankfurt or Amsterdam where you have these very well-renowned schools. Or at Yale University where there is a very good program in fine arts with a lot of talented graduates.

Are there any artists in your collection that you find yourself looking at more and more these days?

Jonas Staal, he’s an artist from the Netherlands. He’s the founder of the New World Summit, a political organisation that tries to put together representatives of movements from all over the world who try to obtain independence. These movements are most often in places with tyranny and no democratic government and they’re trying to obtain their rights. He creates parliaments and moments of aggregation of gathering.

We have New World Summit – Berlin at our house, which is the architectural model of one of the first summits he did in Berlin in 2012. It was in a theatre and you see the architectural model is a circular architecture where the circle is made of the flags of each movement. There are seats inside the circular. It’s amazing because I think that this work really contextualises and visualizes what we call utopian realism. This movement really tries to dream about a transnational unification of all these movements to overcome their difficulties and limits to arrive at a democratic situation. It’s forward thinking on our society; it’s romantic but it’s really powerful at the same time.

When you exchange your experience with others, you are building something, you are not alone anymore because you are sharing your experience so the other one can help you somehow. It represents an artwork for me, because art has to make me dream. It has to make me dream about something different, that does not exist, but maybe can be realized in the future. These give me the tool to think “maybe it will be possible, maybe my daughter or son will see it in reality.” It gives me a very positive feeling about the future, now more than ever. We have no certainty about the future.

What are your thoughts on viewing an artwork in person versus viewing an artwork digitally?

I’ve been to a lot of these viewing rooms, Art Basel and all the art fairs that turned digital. I don’t really trust them, meaning it’s not the experience of the art work. I think you have to experience it. The most important thing of the artwork is the embodiment so you have to relate it somehow. Your body to the space that surrounds you and the work. We didn’t buy works we saw in these viewing rooms, but we did buy some work that we already saw in reality before. We bought one by a very young British artist, Mary Stephenson. I was in the committee of this acquisition award and we had the opportunity to speak with the gallerist, seeing the work through a Zoom meeting, and then speak with the artist as well. I think it was a different experience. We weren’t there physically, but we were there through the words of the artist and the gallerist, which recreated a physical experience.

You’ve also had virtual studio tours on Instagram to support artists during this time. What are some things you appreciated most and learned about during this series?

We started this series because lockdown began when we were in New York, but we decided to go back because the borders were closing. We were supposed to do a lot of studio visits over there because we love to do it when we are in New York but we had to cancel them. When we got back, we thought “why don’t we do it on Instagram so that we share with our followers?” We received very positive feedback from artists because they didn’t stop working. They were keen to show us what they were working on, but not only that. We liked how they were leading their quarantine with a certain type of music, discovering nature, cooking specific recipes, or doing work especially for this specific time. It was very important for them, for us, and for the public as well. We had very good feedback.

We started with artists and we proceeded with curators, with galleries, with art fair directors, we like to understand how all of these people were living their quarantine, but keeping in mind the support of the artists. It was very fun. There was one studio visit with this British artist Marianna Simnett. She does mostly video, very interesting films. She wasn’t too enthusiastic about doing a studio visit. She said, “Sveva, I’m going to be in the studio of my father which is in the countryside and I will dress up.” And she was completely dressed up with wigs, strange makeup, and she gave us a surprise during the studio visit because she was trying to understand a new subject for her film so she was showing this very strange animal she found in the countryside. We had a sort of preview of what’s going on in her next film, so it was very fun. It’s still on our IG channel!

What are some ways you would advise other collectors to support artists?

You don’t need to be rich to buy art, especially if you want to buy emerging artists. You could start to support artists that are graduating from university and try to support them in their first exhibition, meaning also trying to help them in their production. When they start, artists do not even have money to buy the colours and the canvases. I think this is the most precious way to start—to support them from the production point of view rather than buying afterwards. Instagram has become a very important tool for artists but not all artists are good communicators—I mean, that’s why they’re artists, their work speaks for themselves. Maybe you can even help them to improve their Instagram account. That’s very easy for collectors because more and more of them are on Instagram and they know the platform very well and how to use social media. There are a lot of collectors that organise interviews with the actors of the art system. I think that that can be a mediator.

Have you found yourself drawn to a particular style of artwork versus other styles?

Not really, we have no restrictions about medium. We have paintings, we have photographs, we have installations, we have audio installations, we have videos, we have three dimensional reality. I always say to my husband that “We do not have to collect with our ears, but with our eyes and with our heart.” We always try to collect the work that we feel attached to that keeps us emotional. With every work in our collection, I have a story and emotional feelings linked to it—sad or happy. There is a big picture of Marinella Senatore that stands in my living room and it reminds me of a very sad moment of our lives, but at the same time it gives me solace and hope, and hugs me somehow. It gives me tenderness. We are not the type of collectors that collects only, say, German artists from ‘65. When you collect, you have to be very open to everything. I think our artists challenge us everyday with something that we don’t know so much about. They challenge us to discover more, to go beyond our limits, to go beyond our prejudice. That is what intrigues us the most.

What is some advice you have for new collectors?

People who haven’t collected art before a lot of times ask if you do it for pure investment. More and more, buying contemporary art has become a financial asset. This is true—we do not have to hide it. But I think this is a limitation if you see it 100% like this. You have to collect what you like.

Start with an investment. Tell them, “Of course it’s there is no certainty that you’re going to gain thousands of dollars, still if you support the artist, you continue to follow the right galleries, the right artists, you’re going to get something back.” You might not get money back. When our artists are exhibited in museums all over the world or in the public collection of very important institutions, this pays us back. It means that the artist is having a very good career. It’s very positive feedback. Every collector has to invest in the artist long-term. This is important because you have artists that burn out in one season and then they disappear and it’s not good for the artists nor the galleries that support them. I always feel very suspicious about the hype artists, the blue-chip artists, unless you knew them before.

Why are you suspicious of the hype of blue chip artists?

Most of the time, they do not have an easy life. They are kind of like memento mori, we say in Italian. They are like these stars that are born very quickly but die very quickly. We prefer to buy artists that stay with us forever that continue their career, continue to grow, and diversify his or her work. It doesn’t make sense to arrive at thousands of dollars in one year and then look at Oscar Murillo for example. He had a fantastic career at the beginning, but he was too young and he arrived at very high prices in a very short time. Of course he’s still an important artist, but his career slowed down and also museums were not paying attention to him at all at the end. I think we have to be very careful also because we do not have to nurture the fast food consumption of contemporary art. We have to slow down.

Especially during this crisis, we have to slow down. We cannot continue this vicious cycle of buying one and it’s trash the day after. For artists it’s a waste of time, a waste of their life. We lose the importance of being a collector, of being an artist as well. They’re so important for us, for everyone. I think art can save our lives now more than ever. The art we collect is the art, for me, that has to punch you in the face and to say “What’s going on? You have to wake up, this is not going to be good anymore, something has to change.” I think that a lot of artists that we have try to spread these messages.

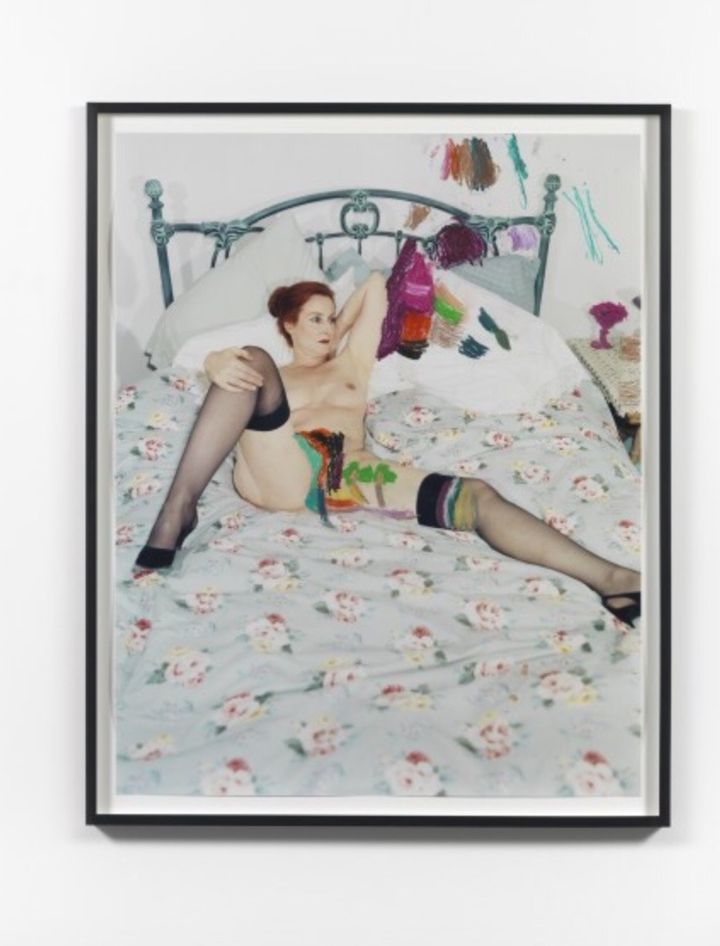

Look at this artist, Leigh Ledare, fantastic artist from California. He’s very famous for the portrait of his mother who was a prostitute. Aesthetically speaking, it’s an amazing picture. His mother is so beautiful, and she’s laying on this bed with a floral bedsheet. It’s a very beautiful picture because his mother’s gorgeous, and at the same time, it’s violent, and there are a lot of very complicated issues. You can be beautiful, but doesn’t mean that you are superficial.

On the contrary, we have another work by this Brazilian collective, Opavivara. They are very famous because they created this instrument that you can play and wear, and they are made of things you can find in the kitchen. When you play this instrument, it gives you joy, but at the same time, they wear the instruments when they do protests in the street against the government against the politics. You can fight with a smile on your face and enjoy it without fighting violently against someone but still protesting and raising your voice.

Where do you see the future of Collezione Taurisano going?

We always say that we are newly born and we’re shaping our identity thanks to the artists we collect, the people we meet. We don’t know where we will go, what we will do in the future, but we will be more than ever a platform, a hybrid version of the collector 3.0. I think collectors that only buy works that sit are very outdated. We feel very engaged about the way we collect. It’s a private collection of course, but we feel it’s very public. Every time there is a group of curators or artists who are in Naples, we always open our house to get to know them to try to understand if they have some links to our collection or not, to share their vision of the art world. We like being open minded. We also like to promote a way of thinking about contemporary art, which really helps us to have a better life and become aware of the things that surround us to fight for the things that have to be changed.

Once the travel restrictions are lifted globally, where are you looking forward to visiting, and why?

That’s a very good question. Before COVID-19, I was flying once a week minimum to go everywhere. I’m really looking forward to going, if it happens, to Artissima in November, which is a contemporary Italian art fair in Torino. They have a very curatorial approach and always do a very good talk program. Also, Torino is a very interesting city and in November it’s the truffle season, so you can get two—art and food.