What’s Going on in the Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith Case and Why It Matters

The art market is abuzz about a recent court decision holding that artwork by Andy Warhol, a leading figure of the Pop Art movement, is not “transformative” and that the artist’s foundation committed copyright infringement when it licensed the reproduction of one of his works. Does the decision represent a shift in the copyright law? Here’s what you need to know.

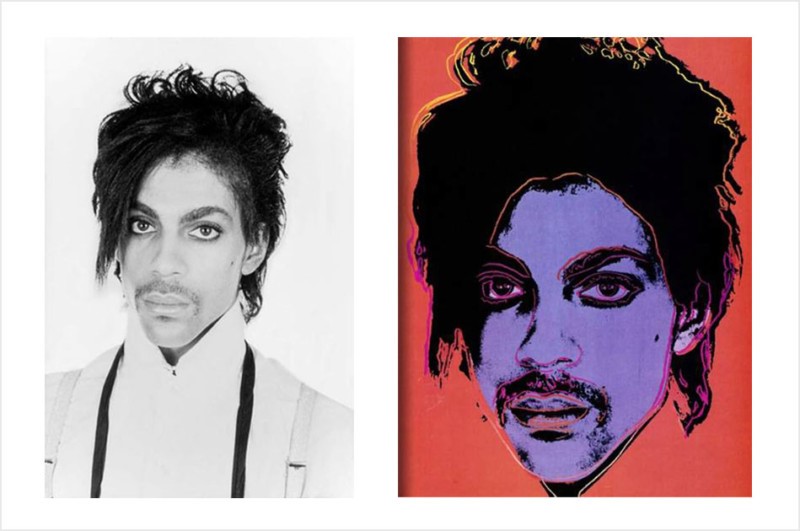

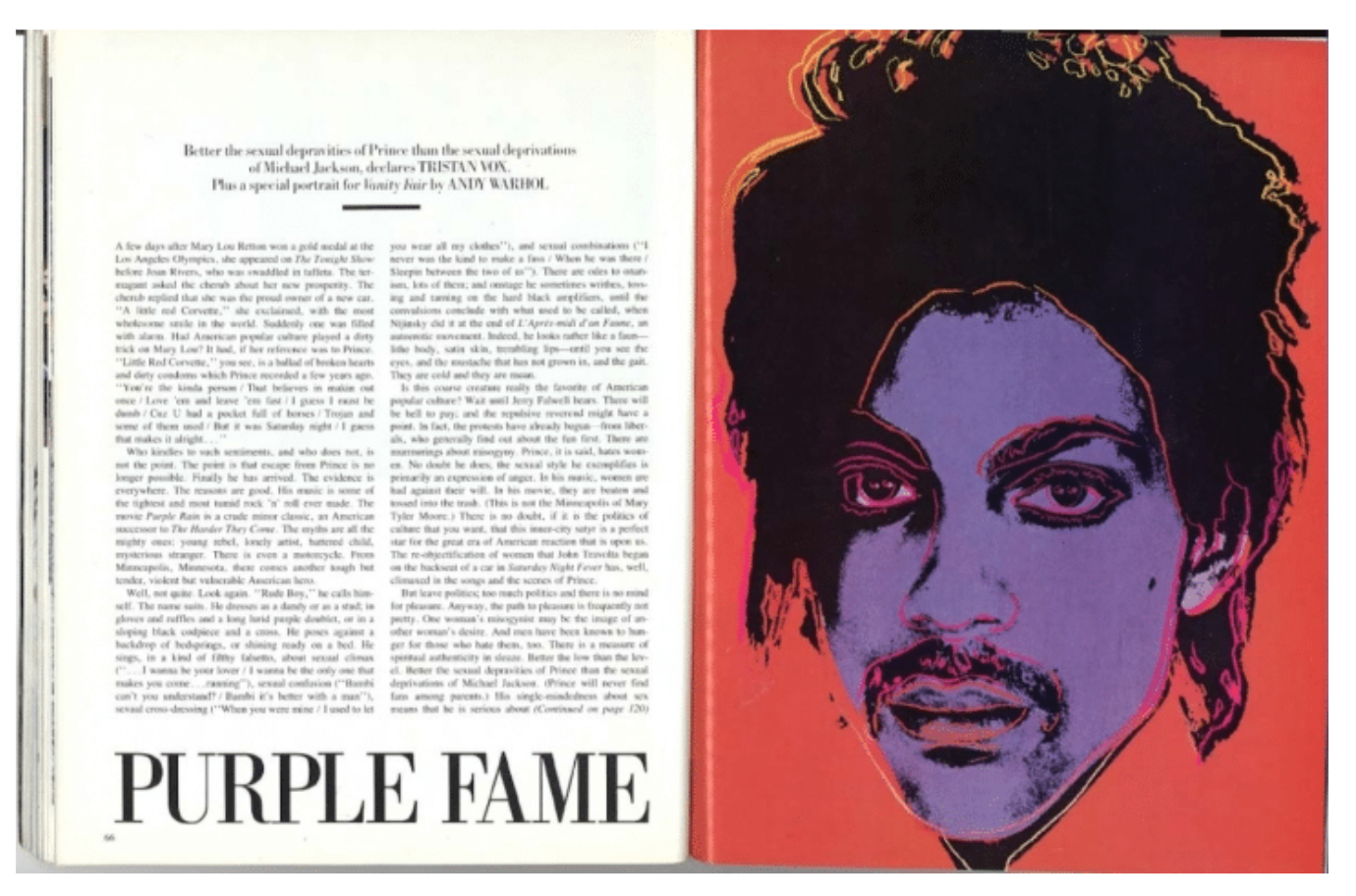

In 1984, Vanity Fair licensed as an artist’s reference a black-and-white photograph of pop icon Prince shot by photographer Lynn Goldsmith. Vanity Fair then commissioned Warhol to create an illustration of Prince, which accompanied an article entitled Purple Fame. Warhol later created 15 additional artworks based on the Goldsmith photograph.

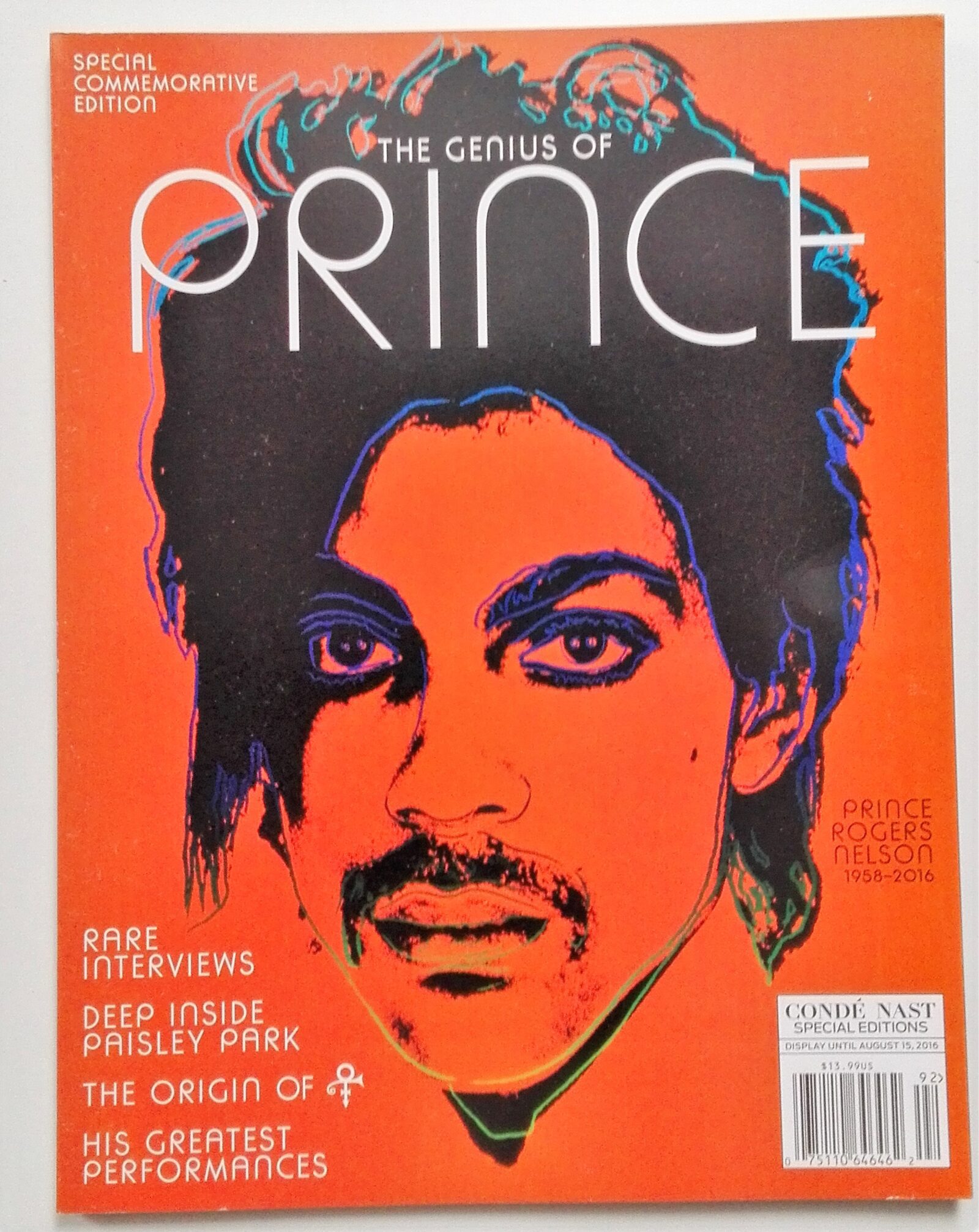

Following Prince’s death in 2016, Condé Nast (the owner of Vanity Fair) issued a commemorative magazine entitled The Genius of Prince and licensed another of Warhol’s Prince series artworks from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (“the Warhol Foundation”) as the magazine’s cover.

After seeing the 2016 tribute magazine, Goldsmith accused the Warhol Foundation of copyright infringement; the foundation subsequently sued Goldsmith in federal district court in Manhattan for a declaratory judgment of non-infringement. On July 1, 2019, the district court held that Warhol’s work made fair use of Goldsmith’s photograph (which is a complete defense to copyrightinfringement). The court found that the Prince series works are transformative – meaning they add something new to the original work, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message. In making its ruling, thedistrict court heavily on a 2013 opinion from the Second Circuit Court of Appeals (which hears all appeals from federal courts in New York) in Cariou v. Prince, which found that 25 of 30 collaged and painted works by appropriation artist Richard Prince made fair use of Patrick Cariou’s photographic portraits of Rastafarians.

Goldsmith filed an appeal, and on March 26, 2021, the Second Circuit (through a three-judge panel) reversed the district court’s decision, finding that the 2016 publication of Warhol’s work in the magazine constituted copyright infringement. In doing so, the Second Circuit made two key rulings: (a) the Prince Series works are substantially similar to the Goldsmith photograph, and (b) Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph was not a fair use.

Substantial Similarity

To be liable for copyright infringement, a secondary user must make a work that is either identical or “substantially similar” to the underlying work. The test for substantial similarity is whether an average lay observer would recognize the alleged copy as having been appropriated from the underlying work. The district court did not decide whether the works are substantially similar because it found that there was fair use, and therefore any copying was permissible under the law.

On appeal, the Warhol Foundation asked the Second Circuit to affirm the district court’s ruling on the alternate ground that the works are not substantially similar. The Warhol Foundation argued that the court should apply the “more discerning observer” test (which has been applied in cases involving works with “thin” copyright protection such as architectural designs, quilts, and carpets) in which one must extract the unprotectable elements and consider whether the protectable elements, standing alone, are substantially similar.

The Second Circuit panel refused to apply this test to photographs, as they are entitled to “thick” copyright protection, even though they capture images of reality. While the panel acknowledged that the issue of substantial similarity often must be decided by a jury, it found that the works are so substantially similar that reasonable jurors could not differ on this issue.

Fair Use

Despite the finding of substantial similarity, the Second Circuit could still find in favor of the Warhol Foundation if the foundation proved that its use of the Goldsmith photograph was a fair use. Acknowledging that the district court was relying on Cariou, the Second Circuit stated that Cariou was the “high-water mark of our court’s recognition of transformative works,” and that, while the Second Circuit was not calling into question the correctness of its prior decision, it believed “some clarification” of Cariou “is in order.”

The court then went through the other cases it has decided involving questions of fair use in the visual art context (two cases involving works by Jeff Koons) and stated: “A common thread running through these cases is that, where a secondary work does not obviously comment on or relate back to the original or use the original for a purpose other than that for which it was created, the bare assertion of a ‘higher or different artistic use’ . . . is insufficient to render a work transformative.”

To be fair use, the secondary work must have an “entirely distinct artistic purpose, one that conveys a ‘new meaning or message’ entirely separate from its source material. While we cannot, nor do we attempt to, catalog all of the ways in which an artist may achieve that end, we note that the works that have done so thus far have themselves been distinct works of art that draw from numerous sources, rather than works that simply alter or recast a single work with a new aesthetic.” Here, per the Second Circuit, the changes made by Warhol to Goldsmith’s photograph were not enough to find the work transformative, as the photograph “remains the recognizable foundation upon which the Prince Series is built.”

Importantly, the court found that, although the primary market for the Prince series and the Goldsmith photograph may differ, the Prince series works pose harm to Goldsmith’s market to license her photograph to publications and to other artists to create derivative works, weighing against fair use.

On April 23, 2021, the Warhol Foundation filed a petition for panel rehearing and rehearing en banc (a review of an appellate decision by the Second Circuit, which is rarely granted). Significantly, the Warhol Foundation argued that the Second Circuit’s opinion was irreconcilable with the Supreme Court’s April 5, 2021 decision in Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc. In that case, the Supreme Court held that the defendant’s line-for line copying of the plaintiff’s software code was transformative because it was for a socially constructive, distinct purpose – the creation of a highly creative and innovative alternative to the original product. In its decision, the Supreme Court stated that an “’artistic painting’ might, for example, fall within the scope of fair use even though it precisely replicates a copyrighted ‘advertising logo to make a comment about consumerism’,” which is an obvious nod to a Warhol work. The Second Circuit then ordered Goldsmith’s counsel to submit a brief on the impact, if any, of Google on the appropriate disposition of Goldsmith’s appeal. Whether the Second Circuit will take any further action in Goldsmith’s case remains to be seen.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Art attorneys have mixed reactions to the Second Circuit’s decision. Some believe that the decision is bad for artists because it takes a narrow view of fair use and may have a chilling effect on artists. Others believe that the Second Circuit got it right, and that the decision provides necessary gloss on the Cariou case.

Will the decision provide clear guidance to artists who are creating new works? How do we reconcile this decision with prior precedent, including Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation LLC, in which another federal appellate court found that the defendant’s t-shirt design made a fair use of the underlying photograph because the defendant stripped away nearly every expressive element that was contained in the source photograph? The Second Circuit said that its finding was not inconsistent with the Kienitz case because the Warhol work “leaves quite a bit more detail” from the source photograph. Is an artist really going to be able to discern the difference between these two cases and understand what sort of copying constitutes infringement?

Troubling to some, including Professor Amy Adler (who wrote an amicus (friend of the court) brief), is the Second Circuit’s fixation on visual changes to the underlying source material, because works that are similar (and even identical) can have different meanings or messages. The Pop Art movement has been around for over sixty years, and it has been over forty years since the artists of the Pictures Generation came to prominence, and the law is still grappling with the legality of these works – even though many of these works have long been displayed in museums. Perhaps some may argue that the question of legality is passé at this point. But new appropriation art is still being made, and the Second Circuit’s decision will impact other cases (including two pending cases involving works by Richard Prince). And the consequences of a finding of copyright infringement can be dire: if works are infringing, museums cannot lawfully display the works, collectors cannot lawfully resell them, and the copyright owner of the source material could seek the works’ destruction or impoundment.

Even if the Second Circuit’s decision is undisturbed, those who value freedom of expression can take comfort in two aspects of these recent fair use decisions. First, the cases suggest that an artwork can be fair use even if it doesn’t make any changes to the underlying source material (provided the artwork obviously comments on the source material).

Second, the Second Circuit’s opinion suggests (but does not decide) that, while the reproduction of the Warhol work in the magazine is infringing, the Warhol artworks themselves may not be infringing because the market for an original Warhol artwork and the market for the Goldsmith photograph do not meaningfully overlap. For all interested in artists’ rights, the Goldsmith case is certainly one to continue to watch.

Amelia K. Brankov is an attorney focused on art, intellectual property, and litigation based in New York and the Founder of Brankov PLLC.