How Dora Maar Defined The Modern Woman’s Multi-Hyphenate Career

A recent retrospective of photographer and painter Dora Maar’s work offers aspiring artpreneurs a glimpse of what a career inspired by the arts, shaped by commercial viability and fueled by political purpose can look like. Between her camera and her paintbrush, Maar cultivated an identity for the modern multi-hyphenate woman.

While Dora Maar is best known as a surrealist photographer, a recent retrospective of nearly 300 objects at the Tate Modern reveals the remarkable breadth of mediums and flourishing creative output that comprised her career. Spanning photographs capturing the social destruction of Spain under the economic depression of the 1930s, landscapes painted in Paris in the 1950s and manipulated photograms discovered after her death, the exhibition seeks to celebrate Maar as a prolific painter and photographer in her own right, beyond her mythologized identity as Picasso’s muse following their brief love affair beginning in 1935.

Maar pushed the boundaries of modernity in several ways, but perhaps most of all in her ability to integrate her lifelong passion for creative expression into a commercially viable career. Despite being financially supported by her parents, Maar chose to pursue photography over painting because of its relative profitability. Without any hint of the “tragic artist” narrative, her life mirrors the current zeitgeist of multi-hyphenate entrepreneurialism that so many aspire to. Amplified by social media influencers who self-identify as “freelance”, and distilled into methodology by books such as “The Squiggly Career”, the pervasive narrative of curating a fluid, piecemeal career is one for which Maar unknowingly helped set the standard throughout the twentieth century.

Born Henriette Theodora Markovitch in 1907, the young photographer began sharing a studio with Pierre Kéfer at the age of 24, when she first began to use her professional name, Dora Maar. Her adoption of this new commercial identity at the studio ‘Kéfer -Dora Maar’ coincided with a period of prolific success, with dozens of commissions from respected couture houses between 1931 and 1935. “This was a really important time for photographers as there was a real boom in the illustrated press”, says Emma Jones, curatorial assistant at the Tate Modern. “Editors were keen to commission photography instead of illustrations so commercial assignments became this important forum for radical imagery.”

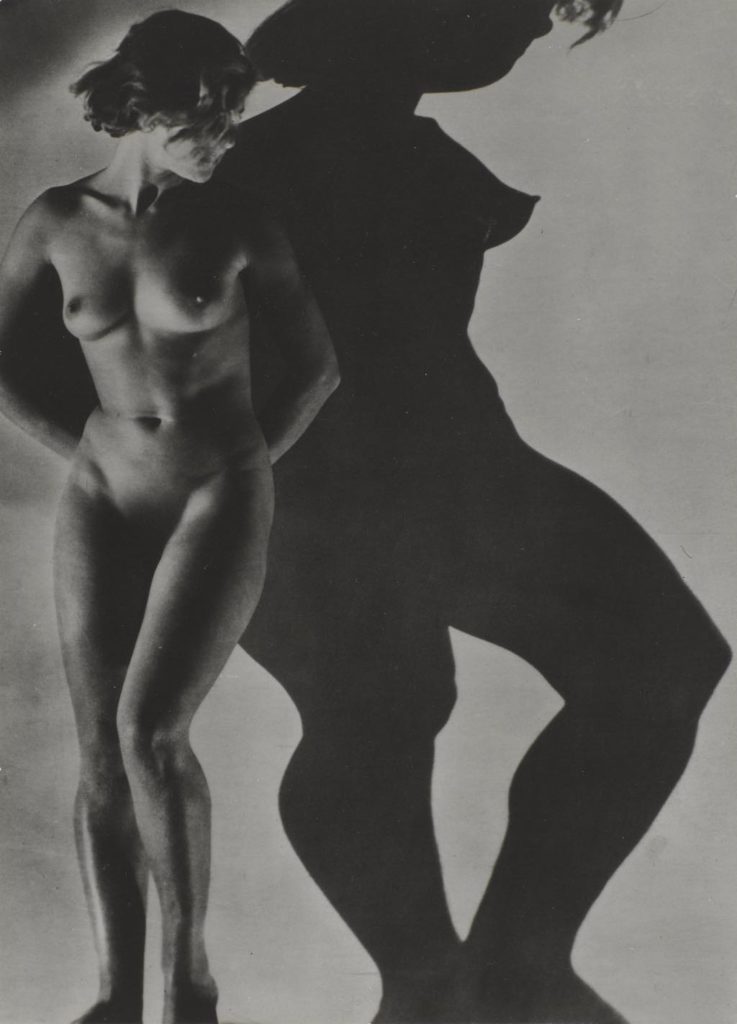

The photography from Maar’s early years at the studio reveals the creativity and experimentation of her on-assignment work. Her photography was commissioned by publications that historically featured men’s work, including 1930s erotic magazines such as Secrets de Paris. Capturing images that elevated the complexity and respectability of the nude form, Maar lent her discerning eye to erotic photography that favoured aesthetics over sex appeal.

Writing on erotic gazes, art historian Alix Agret describes Maar’s nude photographs of model Assia Granatouroff as an expression of Maar’s own confrontation with the mysteries of the men she encountered: “an exploration of the unconscious”. An iconic 1934 photograph, Portrait of Assia on a Fur Rug, depicts the model against a distorted and outsized shadow of her figure. Assia’s silhouette, not her body, dominates the frame, drawing the eye to the flat impression of her body. Her shadow’s most prominent part is her breast, which Assia’s gaze appears to be looking at. While the observer is looking at her nude body, Assia does not meet our gaze: instead, she appears fixated on herself: a freer, less eroticized characterization of her silhouette. Through her lens Maar has reinterpreted Assia’s shape, optically implying a greater story beyond the woman herself.

Maar’s political beliefs aligned her with a coterie of left-wing surrealist artists, and she felt compelled to document the crises she lived through. She travelled alone around Europe off-assignment to places like Costa Brava in Spain to capture the stark realities of society’s most disadvantaged. But despite this sense of duty behind the lens, the impulses of beauty and escapism that art affords its maker never left her.

Maar’s photography represented the zenith of her commercial success, but painting was her first love and the subject of her early study. With Picasso’s encouragement, she returned to painting and developed her own abstract, gestural style throughout the latter part of her career, withdrawing from photography. Maar rediscovered her style and found confidence in her painting work again, says Jones, adding that she was exhibiting in shows in the 1940s before stopping abruptly in 1946, when she was grieving the death of her mother and witnessing the eventual breakdown of her relationship with Picasso. Despite a decade-long absence from the Paris gallery scene, she continued to create in the privacy of her own studio on rue de Savoie in Paris, “probing, at her own pace, aesthetic territories that were uniquely hers”, writes art historian Damarice Amao.

While Maar’s paintings were exhibited during her lifetime, they were deemed obscure after her death. According to Amao, this was rooted in her desire to “remain on the sidelines” of the art scene during a time of “aesthetic renewal.” It’s impossible to know whether she was troubled by this lukewarm recognition of her painting career, he writes. Jones recalls that when the curatorial team were looking into works for the show, they found that several of Maar’s paintings had been sold off in batches at auction houses after her death.

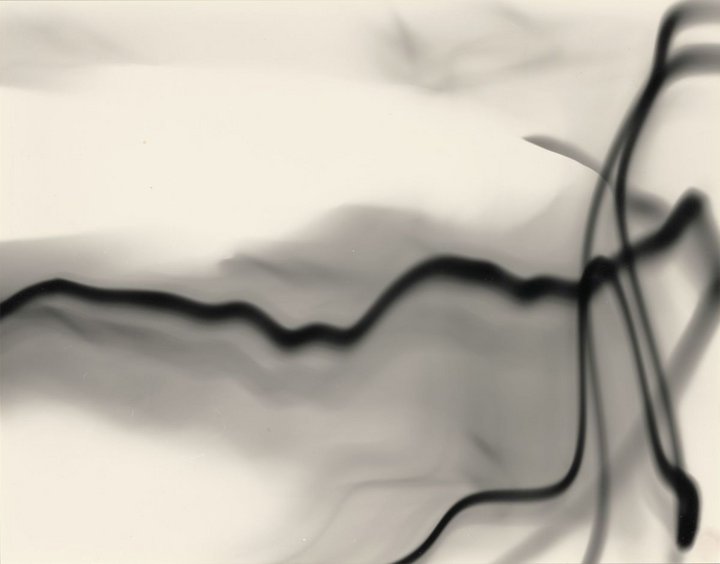

In her seventies and armed with a few decades of experience in painting, Maar re-entered the darkroom and married her two passions of photography and painting. Her photography was no longer focused on what she could capture on the street, but instead on the possibilities of her own manipulation and innovation in the darkroom. “The street has changed so much, don’t you think? It’s more extravagant… but at the same time it’s not interesting anymore, it’s banal,” she said in 1994.

She translated her gestural approach to painting into camera-less photographs made with found objects, producing hundreds of photograms. Among these, forty-eight negatives and nine contact prints, discovered after her death in 1997 and now held in the collection of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, demonstrate Maar’s lifelong commitment to practices of deconstruction and reinvention. “It’s fascinating to see her interest in painting is then continued into the dark room and the works that she made there,” says Jones. “Experimentation really characterises her whole career, from the 1930s up until the 1980s.”

Innovative in her techniques across mediums, —first photography, then painting, then a unique composite of the two— Maar’s art was a product of her experience living through most of the twentieth century. While her bourgeois background enabled her to pursue a varied artistic career, upon her death, Maar’s privilege was largely overshadowed by the focus on her relationship with Picasso. “After she died she was remembered as Picasso’s muse, so the privilege she did have is somewhat forgotten,” says Tate Modern assistant curator Emma Jones.

Perhaps most importantly, the Dora Maar retrospective holds up a mirror to the aspiring multi-hyphenates among its visitors, allowing an audience of artists, photographers, students, writers and painters to locate themselves somewhere within Maar’s oeuvre. The show offers a glimpse of what a flourishing career and life inspired by the arts, shaped by commercial viability and fueled by political purpose can look like.

For Jones, Maar’s ability to straddle several interests at once, united by a common thread of experiment, proves that “we can go out and explore different things, we don’t have to be pigeonholed anymore”. Biographer Victoria Combalia’s description of Maar in The Guardian speaks to the qualities of today’s generation of female artpreneurs: “she was very ambitious. She wasn’t sure which direction she was going in, but she had such energy.”